For fear of finding something worse

advertisement

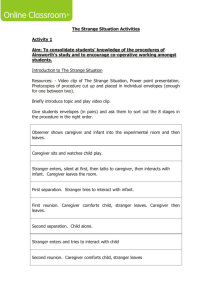

Behavior does not begin at birth or after hatching. Birth or hatching are merely changes in the animal’s effective physical environment, that greatly enlarge the space available to him and the number of physical and chemical influences on him. However… birth introduces the animal to a quite different environment, the social environment, which is much more complex that the physical one. Kuo (1967, p. 30) You know—at least you ought to know, For I have often told you so— That Children never are allowed To leave their Nurses in a Crowd Now this was Jim’s especial Foible, He ran away when he was able, And on this inauspicious day He slipped his hand and ran away! He hadn’t gone a yard when—Bang! With open jaws a lion sprang, And hungrily began to eat The Boy: Beginning at his feet. His Father, who was self-controlled, Bade all the children round attend To James’ miserable end, And always keep a hold of Nurse For fear of finding something worse ‘Jim’ – Hilaire Bellog as quoted in Bowlby (1969, p. 210) Sucking at the mother’s breast is the starting-point of the whole of sexual life, the unmatched prototype of every later sexual satisfaction, to which phantasy often enough returns in times of need. This sucking involves making the mother’s breast the first object of the sexual instinct. I can give you no idea of… the profound effects it has in its transformations… in even the remotest regions of our sexual lives. Freud (1916, p. 314) … probably the feeding experience can be the occasion for the child to learn to like to be with others; that is, it can establish the basis for sociability. Dollard and Miller (1950) The original mother-infant bond is the wellspring for all the infant’s subsequent attachments and is the formative relationship in the course of which the child develops a sense of himself. Throughout his lifetime the strength and character of this attachment will influence the quality of all future bonds to other individuals. Klaus and Kennell (1976, pp. 1-2) Contact comfort is… of critical importance… an infant fed from a lactating wire mother does not become more responsive to her, as would be predicted from a drive-dervied theory, but instead becomes increasingly more responsive to its nonlactating cloth mother. These findings are at complete variance with a drive-reduction theory of affectional development. Harlow and Zimmermann (1959) A child seeks his attachment-figure when he is tired, hungry, ill, or alarmed and also when he is uncertain of that figure’s whereabouts; when the attachment –figure is found he wants to remain in proximity to him or her and may also want to be held or cuddled. By contrast, a child seeks a playmate when he is in good spirits and confident of the whereabouts of his attachment-figure; when the playmate is found, moreover, the child wants to engage in playful interaction with him or her. Bowlby (1969, p. 307) … Group B babies use their mothers as a secure base from which to explore in the preseparation episodes; their attachment behavior is greatly intensified by the separation episodes so that exploration diminished and stress is likely; and in the reunion episodes they seek contact awith, proximity to, or at least interaction with their mothers. Ainsworth (1979, p. 932) Group C babies tend to show some signs of anxiety even in the preseparation episodes; they are intensely distressed by separation; and in the reunion episodes they are ambivalent about the mother, seeking close contact with her and yet resisting contact or interaction. Ainsworth (1979, p. 932) Group A babies… rarely cry in the separation episodes and, in the reunion episodes, avoid the mother, either mingling proximity-seeking and avoidant behaviors or ignoring her altogether. Ainsworth (1979, p. 932) EPISODES OF THE STRANGE SITUATION 1. E introduces parent and baby to playroom and leaves 2. P sits while B plays. (parent as secure base) 3. Stranger enters, sits, and talks to P (stranger anxiety) 4. P leaves, S offers comfort if B upset (separation anxiety) 5. P returns, greets baby, and offers comfort if baby is upset. S leaves. (reunion behavior) 6. P leaves room. (separation anxiety) 7. S enters and offers comfort. (soothability by stranger) 8. P returns, greets baby, offers comfort if necessary, and tries to interest baby in toys. (reunion behavior) Adapted from Shaffer (2000, p. 137) In comparison with anxiously attached infants, those who are securely attached as 1year-olds are later more cooperative… less aggressive/avoidant… more competent and more sympathetic in interaction with peers… [they] display more intense exploratory interest… are more enthusiastic, more persistent… more curious, more self-directed, more ego-resilient— and they tend to achieve better scores on both developmental tests and measures of language development. Ainsworth (1979, p. 936) The implication is that the way in which the infant organizes his or her behavior toward the mother affects the way in which he or she organizes behavior toward other aspects of the environment, both animate and inanimate. This organization provides a core of continuity in development despite changes that come with developmental acquisitions, both cognitive and socioemotional. Ainsworth (1979, p. 936) A central hypothesis within attachment theiry has emerged that suggests that parents’ mental representation of childhood attachment experiences—as manifested in language— strongly influences the quality of their child’s attachment to them… an adult’s evaluation of childhood experiences and their influence on current functioning becomes organized into a relatively stable “state of mind.” Van Ijzendoorn (1995, p. 387) Table 5.1 Characteristics of Inhibited Compared with Uninhibited Children 1. Reluctance to initiate spontaneous comments with unfamiliar children or adults 2. Absence of spontaneous smiles with unfamiliar people 3. Relatively long time needed to relax in new situations 4. Impaired recall memory following stress 5. Reluctance to take risks and cautious behavior in situations requiring decisions 6. Interference to threatening words in the Stroop Procedure 7. Unusual fears and phobias 8. Large heart rate accelerations to stress and to a standing posture 9. Large rises in diastolic blood pressure to a sanding posture 10. Large papillary dilations to stress 11. High muscle tension 12. Greater cortical activation in the right frontal area 13. Atomic allergies 14. Light-blue eyes 15. Ectomorphic body build and narrow face