Industry, Passion, Transformation: Explicating Blake's “The

advertisement

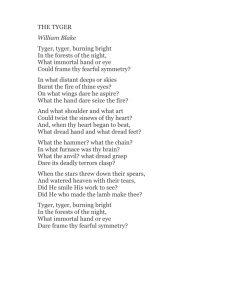

Exploring the Movement and Message of Blake’s “The Tyger” Scott Offutt Nowhere in the Songs of Innocence and Experience are the beauty, wonder, and mystery of William Blake’s work so intertwined, and within such a puzzling framework, as in “The Tyger.” Read alongside its counterpart, “The Lamb,” the poem emerges as a curiosity within Blake’s oeuvre, displaying not only the highly individuated and complex symbolic structure which recurs throughout the Songs, but also a number of dualistic properties which further contribute to the difficulty of its examination. Inherent contradictions between the works, as well as implicit and apparent challenges to religious convention, technological and social progress, and revolutionary idealism, lead to an interpretation of the work not only as an artistic expression but also as a functionally dynamic statement which transcends the limits of form. “The Tyger’s” first stanza paraphrases the most explicit thesis of the poem in the question, “What immortal hand or eye/Could frame thy fearful symmetry” (Blake 197, 34). Herein is one of the poem’s strongest images: the titular tyger, “burning bright/In the forests of the night” (1-2). The repeated address of the aforementioned (“Tyger Tyger”) in the first line evokes an ecstatic mood on the part of the rhetorical figure. Accompanying the intensity produced in the repetition of the name of the poem’s focus is the altogether profound description of the tyger illuminating the woodlands with a somewhat dubious internal fire. Certainly, the description of the “forests of the night” can be considered positive when compared to other portrayals of dark, wooded areas throughout the Songs, as with the imagery of the first “Nurse’s Song,” in which the 1 children trusted to the nurse’s care beg to “let us play” even during the night (Blake 188, 9). Still unclear is the nature of the fire produced by the creature, which may be creative, destructive, or both. When the first lines of the stanza are considered in relation to the question constituting its final lines, the fire and the tyger acquire symbolic resonance as Promethean or Satanic. At first glimpse, the figure wonders whether the subject of the poem could be framed—that is, contained—by even a divine force. The reader, meanwhile, is left to question the tyger’s identity and to consider what it might represent. With the poem’s foremost question asked, new questions develop. In the second stanza, the figure asks “In what distant deeps or skies/Burnt the fire of thine eyes?”, speaking of the tyger in the past tense as if suggesting the range of its experiences and confirming that the brightly-burning fire it produces is internal (“Tyger” 5-6). The final two lines of the stanza stress the tyger’s Satanic (“On what wings dare he aspire?”) and Promethean (“What the hand dare seize the fire?”) characteristics (“Tyger” 7-8). While Blake’s motives for changing the form of address from the second to third person within this stanza are unclear, the tyger’s association with the forces of absolute rebellion and creative potential is firmly established. Perhaps the poet is suggesting that even the forces represented by Satan and Prometheus are somehow incapable of taking hold of the ferocity embodied by the subject. The agents constituting the “immortal hand or eye” of the first stanza are fully envisioned in the third and fourth stanzas, and are rife with nightmarish images of forceful manipulation by various industrial and biological aggressors. Though the tyger has been portrayed as unfathomably powerful, a sense of confrontation—for or against the welfare of the reader and the rhetorical figure—predominates each question. The 2 first, “And what shoulder and what art/Could twist the sinews of thy heart?”, appears to inquire as to whether a human effort could constrain the tyger, as with the question, “What dread hand and what dread feet? (“Tyger” 9-10, 12)” In contrast, the subsequent stanza asks what technological methods have been deployed to confine the subject: What the hammer? What the chain? In what furnace was thy brain? What the anvil? What dread grasp Dare its deadly terrors clasp (“Tyger” 13-16)? The latter stanza is consistent with the former only in its description of a “dread grasp” attempting to seize the subject; otherwise, some device is always involved. This could be taken as a reinforcement of the tyger’s supremacy. Whether forced to rely exclusively on their own strength and insight or the tools of progress, those who would imprison the subject seem as likely to succeed as the “immortal hand” of the first and final stanzas. On the other hand, the question “In what furnace was thy brain?” suggests that the tyger has already endured the aforementioned trials and prevailed (“Tyger” 14). While the imagery of the fifth stanza appears to be inconsistent with the material of the previous four, its questions are central to the appreciation of the tyger’s value within the context of the poem and the Songs themselves. Directly referencing “The Lamb” with the ironic question, “Did he who made the Lamb make thee?”, the rhetorical figure also presents several powerful apocalyptic images and a final indictment of such magnitude as to invite a total reconsideration of the contents of the poem: When the stars threw down their spears And watered heaven with their tears 3 Did he smile his work to see (“Tyger” 17-20)? No longer pondering what force could withhold the tyger’s “fearful symmetry,” the figure instead questions whether God, being aware of the destruction which the tyger will incur or, from the figure’s perspective, has previously wrought, could have produced such an infernal force as that represented by the subject. The repetition of the first stanza at the poem’s conclusion establishes the questions asked throughout as rhetorical. The tyger is unstoppable. Because so many of the poems in the Songs criticize religious conventions in one respect or another, “The Tyger” could easily be misread as a continuation of the trend seen in the first and second versions of “Holy Thursday” as well as “The Garden of Love” and “The Little Vagabond,” among others. Certainly, the notion of divine omnipotence is challenged when the tyger is asked what force, immortal or otherwise, could bring it under control. The poem acquires a tone of bitterness easily misconstrued as satirical when read with its counterpart, “The Lamb.” The rhetorical figure, “Who Present, Past, and Future sees,” has realized that the Creator which summoned the most sublime forms has also produced the horror of the tyger (Blake 191, 2). While the poem is, in a way, a spiritual elaboration, the range of literal meanings that can be attached to God and the tyger becomes too broad to approach the work in a religious context. Like “The Tyger,” “The Lamb” presents a series of questions directed toward a subject displaying qualities similar to the forms it represents, which by the poem’s end are clearly defined: He is called by thy name, For he calls himself a Lamb; 4 He is meek and he is mild, He became a little child: I a child and thou a lamb, We are called by his name (Blake 181, 13-18). The interrelationship of the rhetorical figure (here identified as a child) with the lamb as well as Christ and by extension God provides a hypothetical solution to the problem of the tyger’s true identity in relation to the Creator in “The Tyger.” If the Creator who became a child “calls himself a lamb” and “became a little child,” and the rhetorical figure is a child himself, then both the lamb and the tyger may be viewed as manifestations of humanity and human potential at their best and worst. Furthermore, the subjects of the two poems may signify different conceptions of revolution, with the lamb representing the perhaps naïve view of the French and American Revolutions as the beginnings of a pure, innocent “new age” and the tyger embodying the destruction necessitated by every social upheaval. Like the other poems with counterparts throughout the Songs, “The Lamb” and “The Tyger” enrich one another while exploring the disparities between binary perspectives. Unlike the other works, they are distinct in that the latter poem deconstructs the former with its explicit challenge to the Creator and its portrayal of what He has fashioned. “The Lamb” appears idyllic, even patronising; “The Tyger” is distinguished by visions of trial and destruction, and its subject is without the benign aspect indicated by the lamb’s “clothing of delight” and “tender voice” (“Lamb” 5-7). The influence of the tyger on the lamb, as it were, is profoundly significant, as it indicates a flexibility of vision on the part of the poet and his poetry. Blake may be as disturbed by the question of whether the 5 tyger could be fashioned with the lamb as his rhetorical figure, as uncertain of the tyger’s impact, as fearful that even he, a creator of a different sort, cannot restrict his creation. Rendered more vibrant by its relationship with its counterpart and the Songs of Innocence and of Experience in sum, “The Tyger” thrives as a challenge to spiritual impressions, notions of progress, and the presumptions of readers. Dispelling even the internal pretenses constructed within “The Lamb,” the tyger appears capable of shattering the framework of the Songs themselves. Uncontrollable in the hands of its inventor, the tyger operates without boundaries and thrives within the mind of the reader. More intense than any mundane fire, it continues to rage, transcending all limitations while transforming everything it contacts. 6 Works Cited Blake, William. “Introduction.” Romanticism: an Anthology Third Edition. Ed. Duncan Wu. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006. 191. —. “Nurse”s Song.” Wu, Duncan. 188. —. “The Lamb.” Wu, Duncan. 181. —. “The Tyger.” Wu, Duncan. 197-198. 7 8