chapter 2 - RinaldiPsych

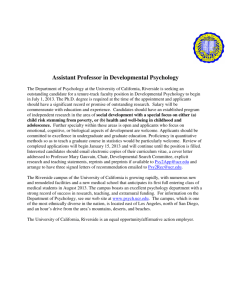

advertisement