Appendix C: Governance in the college sector, Allan

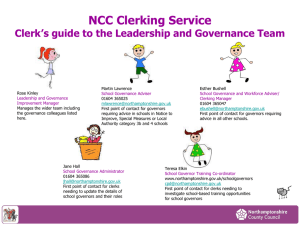

advertisement