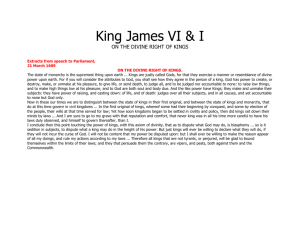

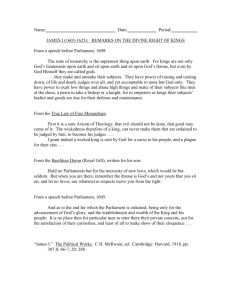

1 Kings》(William R. Nicoll)

advertisement