CACTUS Submission to CRTC 2014-190

Let’s Talk TV Phase III

2014-190

June 25, 2014 by

The Canadian Association of Community Television Users and Stations

(CACTUS)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Identification............................................................................................................. 3

Position ..................................................................................................................... 3

General Comments .................................................................................................. 3

Fostering Local Programming (question 23) .......................................................... 4

Volume of Local Content .......................................................................... 5

Genre Diversity in Local Content ............................................................. 6

Longterm Trends that the Community Sector Can Address ................................ 7

The Threat from ‘Over-the-Top’ Services .................................................. 8

Unabated Media Ownership Concentration .............................................. 9

Assumptions About the ‘Community Sector’ We’d Like to Debunk .................. 10

The Community Sector Involves ‘Only’ Volunteers ................................. 10

Content by Created by Ordinary Citizens Is of Poor Quality ................... 11

Does the Current Funding Model for Community Channels Continue to be

Appropriate? (question 37) .................................................................................... 14

BDU Administration of the Money is Wrong ..................................... 14

But the Amount of Money is Right ................................................... 18

Refining the Community-Access Media Fund:

An Envelope to Stimulate Local Content Production

In Partnership with Public Broadcasters? .................................. 19

Distribution of Community Channels (questions 24 and 26) ............................... 20

Streamlined Licencing (question 62) ..................................................................... 23

Appendix A – Goals and Operating Principles of the Community-Access

Media Fund

Appendix B – Public-Community Partnerships to Improve Local Media

Appendix C

– Cable Community Channel Studios 1989 versus 2014

Appendix D – CLA Support for Library-Hosted Multimedia Production and

Distribution Centres (aka “Community TV”)

Identification

1) The Canadian Association for Community Television Users and Stations

(CACTUS) was created to help ensure that ordinary Canadians have a voice within our broadcasting system. We represent independent non-profit community TV broadcasters, and the Canadians that use and watch them.

We also assist Canadians and communities that want to set up new community-operated television channels or who need assistance to access the community channels belonging to broadcast distribution undertakings.

1

2) We wish to attend the Public Hearing portion of this proceeding scheduled to commence on September 8, 2014, in order to discuss our submission in greater detail.

Scope of Comments

3) Six of the questions in the CRTC’s specific list of questions pertain directly to

CACTUS as an organization that promotes community television and community media. We will reply to these questions first.

4) CACTUS members believe in the fundamental importance of Canadian content, local content, and diversity. We will therefore also comment some of the more general questions in the public notice that touch on these core values. As community television is one of the three elements in the broadcasting system that plays a complementary role in meeting the communications needs of Canadians, we believe our opinion as a representative of the community TV sector is relevant and can add to the more general discussion.

General Comments

5) We have a few general observations to make about the public notice. While we appreciate the Commission’s goal of re-examining underlying assumptions about the broadcasting system in our evolving technological environment, we do not believe the analysis and questions presented in the notice begin to scratch the surface of the underlying challenges facing the

Canadian broadcasting system. It struck us as an attempt to tinker with delivery and format, but in such a way that would fundamentally destabilize the Canadian cultural industry that is fulfilling the public-service objectives articulated in the Broadcasting Act. We feel that there are much more fundamental questions about how to strengthen and improve Canadian storytelling and presence on our screens (whatever those screens are).

These are more important issues than how the content is delivered.

1

For more information about CACTUS, see cactus .independentmedia.ca.

6)

The questions came across as “Well, we’d like to deregulate and retool the way Canadians can purchase and access this program ming” without a due respect for the structural chaos that could result. Subsequent questions about ensuring that “Canadian content and local content would still be available” were like afterthoughts, rather than the central issues.

7) We also do not believ e the public responses to “Let’s Talk TV” consultation phases I and II necessarily supported the questions posed by the

Commission in phase III. In the analysis provided by the Commission, we often felt that the Commission entered the process with a particular bias or agenda that predated phase I, not that the questions grew out of the concerns stated by the public, nor were given the respective weight given the issues by the public.

8) We also did not feel that the original questions posed to the public nor the framework for phase III grew out of the Commission’s stated goals and powers under the Broadcasting Act, nor the Commission’s mandate to make the cultural objectives expressed in the Act a reality. The notice comes across instead as an attempt to deregulate the Broadcasting System as much as possible, with no stated explanation as to how this would benefit the system, Canadians, nor meet the objectives stated in the Act. The thrust of the Act is in fact the opposite. The Act makes clear that the Broadcasting

System is a public resource and serves a civic, democratic, and publicservice function, and as such, merits regulatory intervention to ensure that these objectives are met. Through the process of licencing, commercial players must contribute to those objectives if they wish to extract a livelihood from it. Even the process of licencing is thrown into question by the

Commission, which proposes to eliminate distinctions among different types of licences and to all but eliminate expectations for particular licences (such as commitments to serve particular audiences… what we call ‘genre protection’).

9) Finally, while the public and community sectors are two of the three

“elements” that make up the Canadian broadcasting system according to the

Broadcasting Act, each with important and complementary roles to play visàvis the private sector, we found that the questions in the public notice seem almost wholly to deal with the private sector. In fact, the question posed regarding possible changes to the funding of community television would seem to be an indirect review of the regulatory framework for community television. Obviously, any changes to how this sector is funded will have major effects on how the sector operates and on whether it can survive.

However, the question was not framed in a manner that highlights the potential impact of the question for community television. Participants to the proceeding may not have picked up the importance of the issues for community television.

10) Any regulatory change that will have a profound (and potentially negative) impact on community or reduce the resources available to the sector should be considered in the context of a full review of the community sector so that all stakeholders can be fully informed and provide their comments.

Fostering Local Programming: Question 23

11) Question 23 in the notice in the section “Fostering Local Programming” asks:

“Are there alternative ways of fostering local programming? What role, if any, should the Commission play to ensure the presence of local programming? What measures could be put in place?”

12) Resoundingly, YES, there are alternative ways of fostering local programming! As we have stated in numerous other proceedings, the genuine (independently operated) community sector

—due to its ability to leverage the combined creativity of volunteers and community organizations —can and does produce between 7 and 12 times the volume of programming as the public and private sectors dollar for dollar, in more genres, and drawing on many more community participants and organizations.

2 As such, the community sector (if and when it is given the

2

Because most BDUs today operate community channels as if they were commercial local channels using professional staff with few volunteers, the actual cost of programming of a genuine community-access model has to be interpolated from several sources.

Community channels under the administration of the Canadian Cable Television Association

(the CCTA) distributed an estimated 91,888 hours of original production in 1990, prior to the partial deregulation of community television that occurred in 1997, when production by volunteer producers and crews was still the norm. They accomplished this for $61,650,000, or an average of $671/hour, or $1147 if adjusted for inflation (Canadian Cable Television

Association, Response to Public Notice CRTC 1990-57 ).

This volume and cost is consistent with that reported in the Keeble report for Quebec in the

2008 programming year (posted by the CRTC as input to CRTC 2009-661). Survey results he received showed that 16,609 hours of original production were produced by community groups in that province. While very little hours of original access production was reported for the remainder of Canada for the year (only 6,620), if Canadians in the other provinces had access to production facilities to the same extent as in Quebec, adjusting for population, one might expect a total for the country of 57,272. If one further adjusts for the fact that community producing groups in Quebec are currently within easy access of only 1,700,000

Quebecers or just under 22% of them, one might expect a volunteer-production total of over

260,000 for Canada as a whole, if all Canadians had access to a community production facility as exist in some parts of Quebec today. These two figures bracket the figure estimated by the CTTA for its members in 1990, which confirms that the voluntary sector, when offered facilities and guidance, can produce in the order of at least a hundred thousand hours of original production per year.

freedom and adequate resources to meet its mandate) supplies more volume of local and content and editorial and geographic diversity to the system than any other sector.

Volume of Local Content

13) The table below shows the volume and cost of local production in the public and private sectors compared to the community sector. The column on the left shows the amount spent in each sector, the column in the middle shows how much original content was produced, and the column on the right presents the average cost of that content per hour.

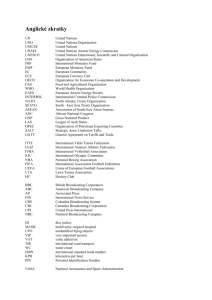

Sector Amount Spent on

Original

Production (Year)

$385,276,803

Hours of Original

Production Per

Year

63,237

Average Cost

Per Hour

Public and Private

Sectors

Interpolated

Figures if Canada

Had a Genuine

Community Sector from Coast to

Coast (see footnote 2)

$130,000,000 200,000

$6093 3

500-800 4

14) When the Local Programming Initiative Fund was operational it generated an additional 234 and 4477 hours of local production nationwide per year in

A hundred thousand hours of production is consistent with public-access original hours produced in the United States, adjusted for population: The Alliance for Community Media, (which represents public-access television channels in the US), reports over 1,000,000 hours of production at public access centres country-wide. Adjusted to the Canadian population, that is over 90,000 hours of production.

3 CRTC response to access to information request A-2008-00071, related to the 2007/8 programming season.

4 The cost of genuine community-produced (TVC) programming in Quebec in 2009 according to the Keeble report averaged $805 dollars per hour. The Fédétvc members’ estimate of the cost per hour of production is lower still, at $563. These figures are consistent with those reported by CACTUS’ seven over-the-air community TV licence holders.

the public and private sectors respectively, or a total of 4711 5 . The size of the fund (at just over $100 million) was roughly equivalent to the size of the current contributions by BDUs to the community sector (over $130 million).

It’s therefore clear that the biggest bang for the buck in the Canadian

Broadcasting system for generating local content is in the independent

(genuine) community sector, whose members were unfortunately never eligible for the LPIF.

Genre Diversity in Local Programming

15) It’s not just the volume of local content that the community sector can deliver better than any other sector, it’s in genre diversity at the local level .

Except for i n Canada’s biggest cities, almost all local channels in the public and private sector produce local news, with perhaps a breakfast or afternoon talk show in midsized city, and not much else. It’s just too expensive for the public and private sector to produce diverse local content.

However, it is not so for community TV. Community-access TV channels produce every conceivable genre from sports and performance mobiles live from events, gavel-to-gavel municipal council and election coverage, programs for children and seniors, arts showcases, book reviews, local dramas from theatres and film and video groups, how-to programs on everything from the stock market to completing income tax returns, and issues programs with participation by phone or on-line.

The community sector, due to its lower cost structure, is therefore capable of producing media in communities that could not consider having a television presence in the public and private sectors, as well as produce a diversity of editorial viewpoints and genres not possible in the public and private sectors even in larger towns and cities where there is a private- or public-sector presence.

5 Figures are derived from CRTC public notice 2012-7882, “Additional Information Added to the

Public File; Weekly Local Programming Averages.” Some caution should be exercised however in concluding that over $100 million generated less than 5000 hours of additional local content, in that the fund was put in place in part to balance the budget losses sustained by local channels as a result of decreases in traditional advertising revenue. Therefore, there is no “control year”; for example, there might have been even less local programming had the

LPIF NOT been put in place.

It’s nonetheless telling that over $100 million generated less than 5000 hours of new production.

The budget of each hour works out to over $20,000 per hour, or more than 3 times the national average in the 2007/8 programming season (see footnote 3).

Two Longterm Trends that the Community Sector Can Address

16) While the community sector has the largest role to play via its contribution to local programming, its significance and value is not limited to local content. This “Let’s Talk TV” consultation occurs in the context of two longterm trends in the broadcasting system that are destabilizing its ability to ensure both effective democratic discourse on matters of public concern, as well as its ability to generate Canadian content.

One is the movement toward video content consumption supplied through OTT (over-the-top) services, delivered via the Internet, which is currently not regulated by the CRTC. This is the immediate context referenced by the public notice, in which there is an assumption that it will not be possible much longer to control or even significantly influence percentages of Canadian screen content to which Canadians will have access.

The second is the unabated rate of media ownership concentration.

The issue of reduced editorial diversity was raised first by the

Commission at the 2008 Diversity of Voices hearing, but the apparent concern expressed by the Commission has not slowed the trend toward consolidation. Since that hearing, Shaw Communications has bought

Global Television. Bell Media has been permitted to purchase first CTV and most recently Astral, leaving no national independent broadcasting networks in the private sector.

The power of the CBC as an independent editorial voice outside the

BDU-ownership groups has also been seriously curtailed in recent rounds of budget cuts.

Both these trends shine the spotlight on the strengths the community sector could be bringing to the Broadcasting system, if it had effective leadership; that is, by the communities it purports to serve.

The Availability of ‘Over-the-Top’ Services

16) The CRTC-published a report entitled Shaping Regulatory Approaches for the Future on the 24 th of March of 2011 as an input to a think tank it hosted for industry players to debate new directions that might be necessary in an

OTT-dominated content delivery environment. The report recognized that efforts to regulate the private sector to offer Cancon might soon reduce their ability to compete with OTT services from beyond our borders, and that more emphasis might soon have to be placed on the community and public sectors

to supply the public-service minded content envisaged under the

Broadcasting Act. On page 7 of the report is the statement:

“Long-term approaches to ensuring the prominence and quality of Canadian production may increase the importance of public and community broadcasters as instruments of public policy. Local and regional programming will also be important, and community broadcasters may play a key role.”

17) We felt at the time that the contribution the public and community sectors might and should be playing in fulfilling the expectations of the Broadcasting

Act had long been undervalued. It always seemed bizarre to us, for example, that multiple production funds had been created to stimulate, cajole and ‘incent’ the private sector to produce programming that it wouldn’t do on its own (because the publicservice nature of such programming didn’t fit a commercial model), rather than ensuring that non-commercial souces of funding were available to fully support content creation in the two sectors that actually have a public-service mandate to produce Canadian content as envisaged under the Act: the public and community sectors.

18) Instead of three distinct and unique sectors with clear and complementary mandates, Canada has had until this point three hybrid sectors with muddled mandates and often indistin guishable programming. We’ve had a strapped public broadcaster forced to raise almost half its budget through advertising, chasing lucrative but extremely expensive sporting contracts with taxpayer money; a private sector that has to be incented to half-heartedly generate

Cancon that doesn’t bring in the ad revenue of big-name US drama series

(and which would happily have supplied the sporting programming); and a community sector that is actually managed by the private sector that no longer trains citizens or facilitates citizen access, but instead churns out fully professional content on soft non-threatening community topics that nobody watches 6 .

19)

So, when we read that it was the CRTC’s considered opinion that an OTT environment might help cut loose the private sector to do what it does best

(compete commercially) and focus public resources instead on the two sectors with a public-service mandate, we welcomed that future, and thought that the stifled potential of the community sector might finally have room to prove itself.

20) So it is ironic and disappointing to find ourselves now at the major review of the Canadian broadcasting system foreshadowed by that 2011 think tank, to find that instead of the CBC/Radio-Canada being strengthened to fill the possible void in Canadian programming, it has been crippled at the knees. It is also troubling to see the CRTC’s “Let’s Talk TV” public notice suggests that

6 Data published by the CRTC as inputs to CRTC 2009-661 (the community TV policy review) revealed that viewership to BDU community channels was between 0.1 and 0.2 %.

the funding formula that directs a portion of the industry’s considerable wealth to communities for their self-expression is now open for renegotiation, and that such negotation might take place outside the context of a full policy review for the community TV sector (question 37 in the notice, which we respond to explicitly below).

Unabated Media Ownership Concentration

21) Furthermore, it is a community sector outside BDU control that can best guarantee that the most diversity of editorial voices reaches the airwaves

(however they are distributed). That sector needs the money that has been ear-marked for it, but liberated from the stifling grip of BDU administration.

22) Every single media merger in our country has made BDU administration of the ‘community sector’ more ludicrous. Apparently, the Commission is willing to hand the responsibility for distribution of our television content, ownership of all our erstwhile independent broadcasters and specialty channels, and the so-called community sector as well to BDUs, all of this while the one national network outside BDU control (the CBC/Radio-Canada) is dealt crippling financial blows by the federal government. When does it stop? When is it too much? Apparently not yet. In this public notice, the CRTC further wishes to ‘streamline’ licencing and remove genre protection, so that anyone can ask for a licence with almost no CRTC oversight, and it will be BDUs who become the sole gatekeepers of content, making decisions on purely commercial terms. This is not what the Act mandates.

23) We are handing ever more power to the private sector in our Broadcasting

System, on the mistaken assumptions that commercial competition will produce public-sector programming and that the private sector can in fact do everything better than governments and citizens. We submit that the private sector cannot make public-service programming as well as the public and community sectors can. It is the public and community sectors that make the biggest and most important contributions to achieving the goals of the

Broadcasting Act. They need to be given adequate support to continue to do so. There’s a reason our sectors exist. There are three elements in the broadcasting system, not just one, for a reason. The elements play complementary and different roles.

24) It has been unbelievably galling for years to stand by and watch the CRTC try to ‘incent’ BDUs to ‘innovate’ community content on new platforms such as

VOD as if posting a video on a web site is a novel thing. Private corporations can’t ‘innovate’ community content. Only communities can ‘innovate’ new kinds of community content. BDUs can only distribute it, and that should be the limit of their role.

Assumptions About the ‘Community Sector’ We’d Like to Debunk

25) We’d like to take this opportunity to debunk some common assumptions about the community sector before we tackle the main and only question in the CRTC’s Let’s Talk TV public notice that deals overtly with the community sector: the suggestion that its funding is open for renegotiation (question 37).

We hear these assumptions voiced or unvoiced at industry conferences, hearings, and in backroom conversations.

The sector is often treated in a patronizing way. Commissioner Michel Morin got it right in his dissenting opinion following the 2010 review of the community sector. He called the new policy (CRTC 2010-

622), “

The

Commission’s paternalistic community model ”.

26) The same attitude is apparent in this Let’s Talk TV consultation, in suggesting that the funding for the entire sector could be rejigged or renegotiated by other industry players outside the context of a policy review to examine the sector’s effectiveness and accomplishments.

The Community Sector Involves ‘Only’ Volunteers, and their Contributions and

Voices are Somehow Less Important than Those of the ‘Professionals”

27) We frequently encounter the assumpti on that community television is ‘just volunteers’ who don’t know what they’re doing, just ordinary citizens who barely deserve a seat at the table. These are the same ‘consumers’ whose needs supposedly underlie the current consultation. But they have a role to play (which is recognized in the Broadcasting Act) beyond just picking and paying for what they want to consume. They are in fact citizens, voters, with informed opinions that they’re supposed to be allowed to air within our

Broadcasting System.

28) There seems to be some ignorance in broadcasting circles that the community broadcasting system employs professionals who are both broadcasting professionals, as well as community facilitators. It’s a demanding role, because you have to set aside your own desire for selfexpression, and share your expertise to make real the aspirations of others for their self-expression, individually, and in communities. These are the

Canadians that we like to talk about as ‘citizens’ and ‘consumers’ when we talk about what we think they need to see on the screen, or how much access to ‘the system’ we want to give them. They’re who we might have been if we hadn’t gone to broadcasting school, or didn’t run media corporations. They’re teachers and students, and nurses and doctors, and lawyers and immigrants and seniors and disabled and all kinds of people who

don’t necessarily feel that they are represented on screens owned by just four ownership groups.

Content by Created by Ordinary Citizens Is of Poor Quality

29) The second assumption about the community sector that seems to make it easy to forget that the Broadcasting Act guarantees a place and a space for ordinary citizens is that content produced today ‘by volunteers’ (setting aside their fully professional facilitators and technical support personnel) will look like a community-access 1980s talk show with a potted plant against a badly ironed curtain. That world doesn’t exist anymore. It disappeared in the early

1990s with easy-to-operate digital camcorders that brought the wars in the former Yugoslavia and Iraq into our homes.

30) It’s not a struggle to teach teenagers to capture well-lit pictures and clean audio on a camcorder anymore. They still need help moulding their message and getting it scheduled in the mainstream, but basic technical quality is not an issue.

31) And strangely (perhaps for you, but not for us), the professional world has validated the community production aesthetic. The reality show, the featurelength documentary that audiences will pay big-screen movie ticket prices to go see, and the Hollywood handheld, less-managed gritty shooting style all underscore the fact that audiences hunger for something more ‘real’, which showcases the challenges faced by real people, not stars.

32) So, in the C ommission’s notice at paragraphs 62 and 63, what does the

Commission mean by “ compelling ”? While on the one hand the Commission admitted that in Let’s Talk TV phase I “What constitutes quality programming varies considerably between individual Canadians and was not fully articulated

”

, the notice goes on to state “The broadcasting system should focus primarily on the production and availability of high quality Canadian programming, including local programming.” What does the Commission mean by “high quality”?

Paragraph 62 suggests that such programming has “high production values, creativity, and tells compelling stories

” without defining what are “high production values ”, “ creativity ” and “ compelling stories ”. We would argue that when ordinary Canadians are allowed to speak and are given the tools to shape their stories with professional support if they need it, that is compelling. CACTUS has community channel footage from Vancouver in which seven-year-old Aboriginal children craft their own stories, and indignantly say to the camera

“We don’t want to be bugs. We want to be superheroes

”. We have award-winning documentaries made by 15-year-old street prostitutes about their experiences on the street. Aside from making rivetting footage, the teenage editor admitted to us that it was the first thing in her life she had ever completed.

That’s compelling.

33)

Some of our most “creative” filmmakers developed their visions on community television, like Mike Meyers at Scarborough Cable, and Guy

Maddin at Winnipeg Videon. Other bullets in paragraph 63 mention the importance of “ diversity ”, serving “ niche and undeserved audiences ”, and removing barriers to enable the entrance of new and independent players:

“The broadcasting system should promote the production of diverse programming that not only appeals to large audiences but also meets the needs of niche and underserved audiences…

3)Barriers within the broadcasting system should be removed to allow a diversity of programming from a variety of sources —big or small, integrated or independent, established or new.”

In giving every Canadian a voice, the community sector has by far the greatest capacity to ensure diversity (if it is allocated resources outside BDU control) and to satsify the needs of niche and underserved audiences. We underscore these points, because these two paragraphs preface the section on “Fostering Local Programming”, and we fear (in combination with question

37), that the Commission may be preying on old and mistaken assumptions about the nature of community programming to create prejudices against a sector that has historically ranked diversity of voices, local production, and serving niche audiences higher than “production values”, even though new technology has largely eliminated any apparent conflict among these values.

34) We would like to point to two current examples. The community-access TV channel in the world that arguably has the ‘highest production values’ and most ‘creative’ and ‘diverse’ content is Okto-8 in Vienna (whose content is available on line, and whose programming schedule is available in English).

Its content and production values surpass most licenced private local channels in the Western World. It has to do with leadership. The channel was established by disgruntled professional filmmakers, journalists, and political activists who felt there was no outlet for their views and content on

Austria’s mainstream media. They had the savvy to get the licence and set up effective training programs for the general public. They are involved in its production themselves, but so are any individual Viennese and community groups that want to be. The channel spends considerable resources helping community groups develop pilot projects (and the community groups themselves want the highest impact for their ideas on television), and they critique every single program that airs so groups are constantly reaching higher bars. Recent programs include a weekly critique of the mainstream news, in which members of visible minorities share how they believe the

‘mainstream news’ that week was biased. On another program, poets find audiovisual expression for their work; a recent episode brought Dante’s

Inferno to the screen. It’s about effective leadership, training, and support.

We don’t have that in Canada, except in tiny pockets where brave communities have managed to fund and resource their own channels. We have a cable industry that either doesn’t believe citizens can produce effective content, can’t be bothered, doesn’t know how to train them, or doesn’t want the alternative views reaching the air anyway (likely all four).

35) But is Canada a potential Austria? On Wednesday night, CACTUS met with over 30 Toronto-area filmmakers, communications students and academics, journalists and representatives of community groups that believe that mainstream TV in Toronto (including Rogers TV, which they view as part of a homogenous mainstream) is not reflective of Toronto’s diverse reality. They want something else. We were frankly amazed at the number of professional broadcasters in the room and film festival representatives who don’t even care at this point whether they get compensated for their work. They just want to see that their voices

—anybody’s voices—are reaching the airwaves.

We are poised to create new Viennas, but the Viennese community channel has strong financial support from the government. Are we any less creative than the Viennese? We don’t think so.

36) Community TV and media is dynamic and inexpensive compared to public and private TV and media, but it does have costs: facilities and trainers/ outreach co-ordinators. Okto-8 has a budget of a million dollars.

37)

So, in answer the CRTC question “How do we make more compelling local content?” Our answer is that you liberate community channel funding from the vice grip of corporations that want to control its content and enable the vast citizenry of this country to mobilize their own expressive capacity. You stop pushing them to the fringes on social media and fragmented platforms like YouTube, and allow them to step back into the centre. You actually give them the access the Broadcasting Act promises. Imagine!

38)

If you’re looking for new ideas to revitalize the Canadian production industry and the capacity for Canadians to tell their own stories, in authentic voices that are rooted in more places than just Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver, you need to re-enfranchise the community broadcasting sector.

39) This brings us to the Commission’s question 37.

Does the Current Funding Model for Community Channels Continue to be

Appropriate?

40) The amount of money is right. It’s BDU administration of the money that is killing the potential for the money to generate the diverse, alternative, hyperlocal content that could be achieved under community administration.

The Commission should require BDUs to pay the money to a Community-

Access Media Fund, as we recommended in 2010.

41) We will answer question 37 in three parts:

We will elaborate on why BDU administration of this money is wrong

We will elaborate on why the amount of funding is right, if it were not administered by BDUs.

We will discuss how it could be leveraged outside BDU-control for maximum impact.

BDU Administration of the Money is Wrong

42) It is throug h the Commission’s policies (based on experiments first undertaken at the NFB) that the community TV sector was created, and it is

Commission policy that continues to allow BDUs to direct between 1.5 and

5% of their 5% contribution toward Canadian programming toward the provision of a ‘community channel’. However, the $130,000,000 that is currently being spent on BDU-administered community channels is not achieving either the volume of local production of which the sector is capable nor the intended window for citizen access. Perhaps the most dramatic indicator of the failure of the BDU ‘community sector’ is the recent complaint against Videotron’s MAtv community channel in Montreal (CRTC 2013-1746-

2). In one of Canada’s largest cities, with plenty of BDU resources and programming expertise (you would think) and right under the Commission’s nose, Videotron is directing between $10 million and $20 million annually toward a channel that the complainant claims is airing not a single production by a genuine ordinary citizen as an act of self-expression. Every single program is professionaly produced, conceived, and executed by Videotron.

With this massive budget (in community TV terms), Videotron is producing

(by its own admission), only 20 hours of new production per week, for an average of $6483 per hour (the professional industry rate, and more than 10 times what TVCs and independent community producing groups require to produce content).

43) CACTUS’ own audit of cable community channels in 2011 (which CACTUS submitted to the Commission and the Commission never raised to the level of complaint) came to the same conclusion that the majority of BDU community channels were meeting neither the local nor access expectations of their licences.

44) The Commission

’s own audits of BDU community channels conducted in the summers of 2002, 2003, 2004 and 2005 found the same thing: where adequate logs and records existed (which they often didn’t), BDU community channels were passing off staffproduced programming as ‘access content’.

This practice was so widespread that Commission staff felt compelled to write a more strict definition of an “access program” in the 2010 policy.

45) We have been allowing BDUs to spend a budget larger than the Local

Programming Improveme nt Fund and twice the size of the NFB’s budget year after year with almost no oversight. No independent fund administration, no vetting of applications submitted by community boards of directors duly elected by their communities, no reporting, no accountability. How is this possible? Would any business in the private sector let a $130 million dollar investment sit idle, with no oversight? Just a management review every 4-8 years while the employees do whatever they want?

46) Well, we might ask, is Vide otron’s and BDUs non-compliance with CRTC policy achieving a different goal? Is the content they’re creating more

‘compelling’ for example? BBMs published at the time of the 2010 review of the community TV sector say, “No it is not.: Even with all that money, and after kicking out those pesky volunteers that want to do potted plant interviews, despite Videotron―the megacorporation’s―best attempts to outdo the community using one of the largest community production budgets in the country , that community is not watching . What we hear anecdotally across the country is that content on BDU community channels may look crisp and HD and well lit, but it’s boring. People will say things like, “Sure, some of the stuff on the community channel back in the day may not have been well lit or a volunteer had trouble getting good audio on a shoot, but there was lots of creativity, the programming generated debate, the community had a voice and a mirror for itself . Local decision-making changed, because that channel was there

.”

47) We might also ask, what is the public getting for that $130 million a year if no one is watching and no one is getting training or being given access to tell their own stories either (which is after all, the main reason for community channels, that is supposed to set them apart from channels in the public and private sectors)? Are we at least getting audio-visual records of communities across Canada? Have we built an amazing audio-visual archive of the 294 cable community channels that Frank Spiller says used to exist in 1982 7 ?

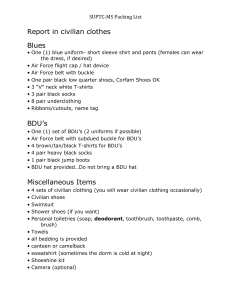

No? Why not ? Because BDUs have closed most of those 294 studios, and have put those audio-visual archives in dumpsters .

7 In his 1982 report “Cable Community Programming in Canada”, Frank Spiller reported that there were 294 “active” community TV channels on cable in Canada. The report is available in the CRTC’s library. While we don’t know exactly where these studios were located in

1982, we know where 323 were in 1989, thanks to the Matthews Cable TV Directories (see appendix C).

48) While every book published in Canada has to have a copy registered with the

National Archives of Canada, this protection of our cultural record has not so far been extended to community channels. For example, although I (the writer of this brief, Catherine Edwards) no longer worked at Shaw Calgary when Shaw made the decision to empty its archives of all the video programming it had recorded since the 1970s, I got a frantic call from the traffic co-ordinator the day the tapes went the dumpster in the early 2000s.

She said, “There are thousands of tapes going in the dumpster. Can we salvage some somehow?” I put out calls to former volunteers whose video masters (3/4 inch at that time) were in that dumpster encouraging them to go save them. Volunteers used to make VHS copies off air of their productions, and the masters were kept by cable companies. No copyright stipulation existed to protect their productions, as in the c urrent “Code of Access Best

Practices”. I know some of what went in the bin that day. One was an award-winning production about the history of the Calgary Stampede, and the Calgary’s founding chuckwagon families who live on the stampede circuit.

I later heard that VideoPool in Winnipeg had managed to save some of the episodes of Guy Maddin’s early zany attempts at Videon (also owned by

Shaw in the late 1990s). It was a show called Survivor , that lampooned coldwar bunker-building. The first manager of Winnipeg Videon (Dorthi

Dunsmore), managed to deposit three VHS copies of early programming from Winnipeg with the Manitoba Archives. All across the country, these gems have been lost. Smaller communities have been even more betrayed.

Not only are their production studios gone, with no presence by public and private broadcasters, they’ve lost in many cases—the only audio-visual records of 40 years of their social, political, and cultural history reaching back to the late 1960s. So this is what we have to show for entrusting BDUs with roughly a billion dollars per decade to develop and foster new talent and reflect communities back to themselves: precisely nothing. It’s all gone.

So, in answer to question 37, Does the current funding model for community channels continue to be appropriate?

We say “No, it is not appropriate”.

This funding should not be administered by BDUs.

49) Why not create the “Community-Access Media Fund” we proposed at the

2010 Community TV policy review so that this money can be effectively deployed and monitored under an independent fund structure, equivalent to the oversight the Commission gives to the 3% BDU contribution toward the

Canada Media and other conventional television funds? This is the simplest

‘measure’ the Commission could take to foster more local and diverse programming in every genre and every ‘market’, and fulfill the goals and objectives of the Commission Community TV policy and the Broadcasting

Act. The deployment of this money would then be accountable at two levels:

To the fund, which would vet each application and which would have deliverables and a reporting procedure in line with reporting requirements for other CRTC-recognized funds.

To the community-elected boards of directors of each applicant channel.

50) We note that the Commission expressed its concern about BDU accountability during the 2010 community TV policy review. One of the questions in the notice asked:

“

Is there sufficient accountability regarding the amounts terrestrial BDUs are allowed to direct to community television?

In the new policy that resulted, the Commission made this statement at paragraph 65:

“ The Commission agrees with many parties that there is a lack of accountability and transparency regarding how BDU contributions to local expression are spent.”

51) Creating a Community-Access Media Fund that would transfer control of this resource to communities

—where that control belongs—is the single most important tool the Commission could put in place to leverage the $130 million spent by BDUs on their own ‘community channels’. Overnight, instead of fewer than 50 remaining BDU community channels (since the rest have been closed) generating an estimated 20,000 hours of pseudo-professional content that is indisinguishable from the fare on private lifestyle channels, more than 250 communities could generate 200,000 hours of programming country-wide, in more than 200 communities that currently have no presence by a television broadcaster, and while fulfilling the CRTC’s community-access mandate and a digital media training skills mandate to serve the digital economy to boot. We reattach the document we prepared during the 2010 community TV policy review for how the Community-Access Media Fund could be structured, to which we have added a significant new addition, which we discuss below.

52) This money and capacity is already within the broadcasting system, but the money is not deployed effectively. It has been within the straitjacket of BDU control, with the inevitable result that it is used to serve their own selfpromotional ends. The extensive capacity of communities and community volunteers is not being leveraged. The money and communities are being kept apart through BDU administration; they are not being brought together for their maximum bang for the buck.

There are numerous additional reasons (aside from the lack of true access, and the resulting lack of diversity and volume of content), why the BDU model of community channel administration is long past its due date (and should have ended in 1991, when the sector was recognized as ‘mature’ and included in the Broadcasting Act for the first time):

Since cable companies have interconnected their systems fibreoptically, they have removed the cable head ends that used to receive the microwave signals in small communities. Cable community studios used to be collocated with these head ends, and have therefore also been closed. Cable companies have gone to the CRTC repeatedly to ‘zone’ these smaller systems, which enables them to meet the 60% minimum of local programming that they’re supposed to do in each licence area over larger and larger areas. While the cable companies’ rationale that the

5% of revenue they collect in these small licence areas is insufficient to maintain a production studio and staff with the head end gone is true, neither the cable company nor the CRTC has ever seriously considered that the small amount that might be collected (say a few thousand dollars) could be leveraged by community resources already on the ground in those communities such as libraries and schools. They could deliver the hyperlocal community media services that the BDUs have admitted they cannot. In just the same way that there used to be economies of scale for the head end to be collocated with a small studio and to share one employee, the money could be deployed on the ground by community organizations. Small communities have completely lost out, and now see remote programming piped into their regions on the

BDU ‘community channel’.

Cable market share hovers at around 60%, so cable-only community channels can't function as a "digital townhall" for communities anymore.

Cable community channels once gave citizens access to the latest in media training and technologies (TV at that time). To be meaningful, the community media centre of today needs to offer multiplatform, multimedia training, providing access to the newest tools of the day, whatever those are. This is possible at a community-based resource (like a library), not at a BDU-operated community channel.

Canadians are used to communicating directly with one another thanks to social media. The day when it was appropriate for cable companies to

'gatekeep' community-created video content is long gone.

The more consolidated BDUs have become, the less and less appropriate it has been for them also to control what is supposed to be the alternative, grassroots "community sector". The community sector should be the safety valve outside the corporate system, but it is less and

less able to play this role, the more consolidated the corporate sector has become.

The CRTC doesn't have the resources or will to police BDUs to follow community channel policy. Our experience over the last decade confirms our point.

Question 37: But the Amount of Money is Right

53) At the time of the 2010 Community TV policy review when CACTUS first proposed that the BDU-contribution to community programming should be directed to a national ‘Community-Access Media Fund’, we conducted a statistical analysis of the Canadian population, and determined that only 168 communities in Canada have more than 10,000 people. There were just less than 300 cable community channels in Canada, which means that every town or village that had 10,000 people or more likely once had a cable community channel. In addition, bigger cities like Calgary and Ottawa had two, and the biggest cities like Montreal, Vancouver and Toronto, had as many as 12 neighbourhood offices at which citizens could access training and production facilities for what was then the new medium of the day: television. Many towns with fewer than 10,000 people also had cable studios. This is a level of access to media literacy training and local expression that is unheard of today, but just as vital as ever, as media tools proliferate and the digital economy is the economy of the future.

54) In our analysis, we calculated that to restore media access and training to

90% of Canadians (such that they could reach a multimedia community production hub within 30 minutes on public transportation), it would take 250 such centres. $130 million is enough to fund 250 such centres, with an average budget of a half million dollars. This is on average half a municipal library budget, calculated by cable licence area. T hat’s what you need to facilitate effective citizen access to media, and to position all Canadians to participate in and contribute to the digital economy.

Refining Our 2010 Community-Access Media Fund Proposal

55) In 2010, we developed goals and a structure for the Community-Access

Media Fund, so that every penny would be accountable to Canadians as taxpayers and cable subscribers, to the CRTC, to the broadcasting industry, and to community members on the ground. We developed reporting requirements and targets that community-managed boards of directors would commit to when applying to the CAMF.

56) During the intervening four years, we have refined this model and we would like to present two of those refinements here:

1) Collaboration with Public Libraries, as Well as Other Existing

Organizations

In our original document, we described in some detail that our vision was not to reinvent the wheel, but to build on the capacity of existing organizations in communities across Canada that have lost access to cable community channels, so that they could function as full digital multimedia production and distribution facilities. For examples, existing community radio channels might expand their capacity to offer training and distribution in video and web design (so far, seven have indicated their interest to us, since the NCRA’s 2014 AGM in Victoria). Video cooperatives that already train and offer equipment access to their communities, might get licenced. Former CAP sites (Community Access

Portals funded by Industry Canada) might beef up their training offerings and add distribution of content to their mandates, and so on.

One of the most exciting possible collaborations we envisioned then and have since pursued is with public libraries, many of whom are reexamining their roles, and are already offering “maker spacers” where the public can experiment and access a range of digital tools, We are encouraging them to consider taking their mandates one step farther… providing a local distribution platform for the output of that training and experimentation. Several are starting to work with us toward licencing.

Public libraries still exist as the central delivery point for media literacy resources in communities small and large; enhancing their capacity to offer Canadians media literacy training in video and multimedia production is a natural extension. We reattach the Canadian Library

Association’s support for this vision from the 2010 Community TV Policy hearing.

2) Collaboration with Public Broadcasters

Karen Wirsig of the Canadian Media Guild and CACTUS co-wrote a research paper in the spring of 2012 entitled Public and Community

Partnerships to Improve Local Media 8 . In an environment where actual communities have no access to the signficant resources that BDU direct toward their own ‘community channels’, and the CBC/Radio-Canada

8 This paper was presented at the Journalism Strategies conference at McGill in the spring of

2012, as well as at IAMCR (Interantional Association of Media and Communications

Research) conference in Durban, South Africa, and will shortly be published in a collection of papers from the Journalism Strategies conference. It is included as an appendix to this submission.

faces budget cuts so deep that they are impairing its ability to create local content and be present in our regions, the Guild and CACTUS decided to partner to propose a model of partnership that could leverage the strengths of both sectors to create more local content. In a nutshell:

-

With the community’s help, and the use of community resources and facilities, the public broadcaster might source more local and regional content and maintain a presence in more places.

Through working with the public broadcaster, community-based producers might find wider distribution for work of national and regional importance, and benefit from work placements and exposure to CBC journalistic methods and practices.

CACTUS is currently in conversation with the CBC about how these ideas can help offset the spectre of less local content on the CBC, and enhance its capacity for more local and regional production. We note that in Dominque Payette’s 2012 report, L’information au Québec: Un int érêt publique , recommendations 18 and 19 on pages 96 and 97 respectively, suggest a similar co-operation between Quebec independent community TV corporations (TVCs) and Téléquébec, as a way for the latter to source more local content and be more representative of Quebec’s regions.

9

Specifically, our report (which was previously submitted to the CRTC when the LPIF was being reviewed) recommended that an envelope of funding be created to promote partnerships between public and community media. At this time, we recommend that if the 2% that BDUs are currently permitted to direct toward their own ‘community channels’ is instead put into a Community-Access Media Fund to which not-for-profit community groups can apply to operate multimedia community production and distribution centres, that an envelope within that fund be used to facilitate public-community partnerships .

Such an envelope can help offset the negative impacts of CBC local programming cuts and develop the capacity of the community sector at the same time.

57) We point to the existence of this report and these ideas as evidence that it is the community sector that is the source of innovation in community production, not BDUs.

Distribution of Community Channels

9 http://www.ledevoir.com/documents/pdf/rapportpayette.pdf

OTA Distribution

58) Questions 24 and 26 ask about OTA distribution of local channels, of which community channels are a subset.

59) As a sector, we believe that yes, there are compelling reasons to maintain

OTA distribution of local channels (not just community channels):

OTA local channels improve the chances that Canadians who cannot afford or do not have access to basic cable, satellite, or broadband

Internet will at least have access to a local broadcaster, whether a community, public, or private-sector channel. As we proposed when the

CBC/Radio-Canada was given the green light by the Commission to shut down its extensive network of over-the-air transmitters in 2012, if free to air coverage is shrinking, it needs to be replaced by a free skinny basic package on cable and satellite, which includes the national and provincial broadcaster if there is one, community channels, and local broadcasters.

In times of emergency, there must be a way for real-time messages to reach everyone in a community, regardless of their ability to pay for television services.

Local broadcasting towers convey some control by local entities (private, public, or community) over the communications infrastructure. For example, many of our members operate in remote areas where residents can’t afford satellite services and there is no cable network. The community/municipal tower is used to offer a lowcost ‘skinny basic’ including the community channel, the CBC, and a handful of other television and radio services that the community selets for itself. Local towers under municipal control can also be used to offer broadband

Internet. These services are more cost-effective for municipal and community entities to offer than ever before, thanks to the ability to multiplex digital signals (technology that has so far been underutilized in

Canada). The golden age of over-the-air television is just dawning, yet

Canada seems to be turning its back on new technologies, in favour of control of our system by BDU oligopolies.

We believe the option of local redistribution is critical in the current environment of media ownership hyperconcentration. There must be a competitive balance to ‘the big four’ that rests in communities’ hands. It’s about increasing consumer choice and local content.

60) We do not agree with the Commission’s analysis at paragraph 67 that “the costs of maintaining OTA transmitters and, in most markets, digital television

(DTV) transmitters” is a significant burden for local channels. Our smallest

member (with revenues of roughly $8000 per year) easily maintains a broadcasting tower. The maintenance costs are negligible. The initial installation costs are significant, but once installed, a tower and transmitter just need power. And even the installation costs are lower than ever before.

Second-hand digital transmitters start as low as $10,000, and can be used to multiplex 6 or 8 standard-definition TV signals,or TV with broadband Internet, or with radio. Local broadcasters can easily cost-share if they so choose.

Turning our backs on digital transmission technology when the digital transition happened only 3 years ago is surely premature. We haven’t begun to tap its potential.

61) Every one of our OTA members wants to keep broadcasting, and values the autonomy that their towers convey. They also value the fact that broadcasting ensures their carriage in the basic BDU tier (although their status as a community channel might guarantee this status even if they were not distributed over the air).

Inclusion in the Skinny Basic Package

62) Paragraph 41 in the notice provides four bullet items describing what might be included in a Commission-mandated

“skinny basic” package.

63) As stated earlier and also in other proceedings, CACTUS believes that the skinny basic package should be free, to ensure that all Canadians (who are taxpayers) have access to the services of public and educational broadcasters, community broadcasters, and other key services that fulfill a democratic function like CPAC and provincial and territorial legislature channels.

64) There is an apparent inconsistency in the list in paragraph 41, however. Local channels are mentioned (which includes local OTA community broadcasters).

We are glad to see this. However, the fourth bullet raises the spectre that

“community channels” might not be included in a skinny basic package to be carried by all BDUs.

65) We note that communities can obtain digital-only cable licences (without an

OTA component) and that these services should be included in the skinny basic package available in an area, if the channel originates in that area.

Community channel policy stipulates that this is the case, although there is currently a grey zone in Commission policy with respect to these channels, because they are not mentioned in the BDU exemption order as having mandatory carriage.

66) There is the possibility that a community might request such a licence, and then not have carriage if the community happens to live in the licence area of an exempt BDU.

67) So, we would request that community channels always be part of the skinny basic package carried by BDUs and are puzzled that the fourth bullet in paragraph 42 would introduce incertainty:

The Broadcasting Act makes it clear that the system comprises “public, private, and community elements”. There is typically only one representative of a “community element” in any one licence area, so it should be carried, just as there is typically only one or a very few publicsector channels, versus the dizzying number of private options. Any public and community channels available in a licence area should be carried, because of the high contribution they make to the public-service goals identified in the Broadcasting Act.

Community channels cannot function as a “digital townhall” to reflect communities back to themselves if they are not carried on all television platforms by which the members of a community can obtain TV services.

The Commission’s recent practice of encouraging and allowing different

BDUs in a licence area to offer competing ‘community channels’ is not in alignment with the mandate of a community channel and has just served to fragment the resources available to them.

Community channels (both those programmed by BDUs as well as independent community channels) are required to air 60% content local to the licence area, and 80% Canadian content. CACTUS independent licence holders typically air close to a 100% local and Canadian schedule. Given the challenge the Canadian Broadcasting System faces to produce enough local content, it’s imperative that this wealth of content be available to all residents of the community where it is produced.

68) Similarly, independent community channels should be given priority carriage in the skinny basic package of DTH service providers. We note that when

Bell bought CTV, seven of the nine independent community channels that exist in Canada (all of CACTUS’ members) were uploaded to Bell’s basic tier among 43 additional local services. At the time, we were told that Shaw would not be asked to carry independent community channels (nor the other local public and privatesector channels) because the company didn’t at the time have the same capacity as Bell. We have since been informed that this is no longer the case, and that Shaw has acquired access to an additional satellite.

69) This being the case, we would ask that it become part of standard policy that independent community services have priority carriage on all DTV services

(questions in paragraph 49).

As enumerated above for cable skinny basic packages, for the community channel’s democratic mandate to be met, it must be available to all residents of an area, regardless of both their ability to pay or their choice of TV service platform.

The community channel’s high percentage of unique local content (as opposed to time-shifted and duplicate copies of US content that often occupies bandwith on other channels) should qualify it for inclusion in the

DTH skinny basic package.

We note that in the rural areas where our member channels are available in Bell’s basic service tier, for the first time community members that live outside a cabled downtown core on rural farms are able to participate fully in the life of their communities via the community channel. Where there is no presence by a local or public broadcaster (which is the case for most of our members), this access to a community channel is essential.

Streamlined Licencing (questions 62)

70) In general, CACTUS doesn’t support the proposed streamlined licencing scheme. We believe category A licences should be maintained. If licenceholders are willing to make significant contributions to Canadian programming, then they should be accorded mandatory carriage. The

Broadcasting Act makes it clear that it is the CRTC’s role to make sure that a variety of high-qual ity Canadian content exists, and so it is the CRTC’s responsibility to scrutinize licences. This responsibility should not be devolved to BDUs.

71) With respect to community channels in particular, we take issue with footnote

23, which states,

“Community channels commonly operate as part of the

BDU licence and, as such, would not be licensed separately as basic services.” While it may be true that BDU-owned community channels

‘commonly operate as part of the BDU licence’ today, this is only true of BDUowned licences, and ignores:

Independent community-TV licence holders (such as CACTUS members), which already hold independent licences

TVCs in Quebec, which are not-for-profit corporations incorporated for the sole purpose of producing community channel content, which have

repeatedly requested to be independently licenced. The F

édétvc renews its request for independent licencing for its members today.

Our argument in the current brief that no community channel should be simply “part of” a BDU licence. Communities are not being served under this system, because BDUs are no longer resident in most communities nor can be responsive to their needs. All communities should have the opportunity and the financial support (from BDU funds ear-marked for this purpose) to apply to the CRTC for separate licencing, as occurs in the community radio sector.

72) We thank the Commission for the opportunity to comment in this process.

* END OF DOCUMENT * *