Sarah Clinch

advertisement

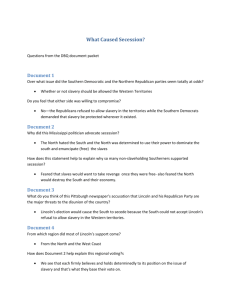

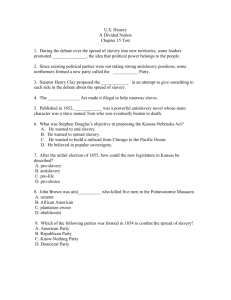

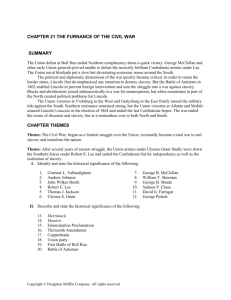

Sarah Clinch CAP 225/ What is Good Dr. Ethan Lewis 11/30/2007 Three Generations of Change “Coming generations will learn equality from poverty, and love from woes” (Gibran). Patriotism, or love of country, more often than not defines America and its citizens as a whole. My favorite poet, Kahlil Gibran, has spoken (quite unknowingly, I’m sure) for every black freed from slavery to walk the path of Reconstruction into the land of equality. The pivotal Civil War era became a turning point for the nation in many ways, and the three generations who dealt with that period: the slaves of the time before the War, the slaves during the war, and the freed blacks in the generation maturing during Reconstruction, all rode the roller coaster of the Civil War to the end. Two great examples, and novels which I will use to showcase these times and the people who lived them, is Howard Fast’s Freedom Road, and Octavia Butler’s Kindred (which I read for another of my classes this semester and found to help me in my understanding of the PreCivil War era). The book chronicling Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Douglas in their debates before the war, The Crisis of the House Divided by Harry Jaffa, helps us delve into the mind of the great leader of the Union during the War itself. Both novels, as well as Jaffa’s book, deal with the concept of slavery, though in very different ways. Fast’s novel deals with the time of Reconstruction after the War, and how the former slaves dealt with their newfound freedom. Butler’s novel deals with the concept of slavery before the Civil War, juxtaposed with the modern 20th Century. Jaffa’s book deals with Abraham Lincoln in a record of his debates with Franklin Douglas, analyzing his political philosophy, therefore dealing in part with his views of slavery and his methods during the Civil War. By examining each work through Gibran’s quote, aka “equality from poverty” and “love from woes” (Gibran), we can perhaps come to a better understanding of how much the African-Americans were affected by the Civil War. Gideon Jackson and the other blacks living on the bankrupt plantation, in Howard Fast’s Freedom Road, deal daily with the issue of poverty. As newly freed slaves, they receive rights as free men, but no possible means of attaining a life off the plantation. Since every black on the plantation received their freedom in the same time, each black on the plantation received their poverty in the same moment. These men, women, and children, a microcosm of the rest of the black population at the start of the Reconstruction era, live through devastation; and yet, they never quite lose their hopes. Gideon Jackson, the main character of the novel, becomes a representative for the Convention held to discuss the New Constitution. He leaves the plantation he has lived on for perhaps his entire life, and stays away for the better part of six months (Fast). The estrangement from his loved ones, while terrible in its extremity, nevertheless strengthens Gideon’s feelings toward his family and friends, and becomes his hardship to bear throughout his time with the Convention. The strengthening of his feelings alludes to the “love from woes” Gibran mentions, and gives Gideon the heart to continue on his path. In the Reconstruction era, equality among blacks exists, even if the equality rests in the poverty they share. Almost impossible to move up, the blacks’ social status remained as the lowest of the low, yet somehow they found the strength to carry on, and to get things done, and eventually, to beat the social constructs formed against them to move up in the world. Where did this strength come from? The love they held for the people they cherished brought the former slaves strength in the dark times of the Reconstruction era. Dana, a modern black woman working in a “casual labor agency” (Butler 52), leaves her comfort zone, not to mention her “time” zone, when a distant ancestor of hers pulls her back through time so she can save his life. The science fiction novel explores the “grandfather paradox,” in which a character affects her life by changing events in the past. The ancestor, Rufus, who brings Dana to his own time, happens to live in the Antebellum South in 1815. This pre-Civil War era still has slavery, and Dana, as a black woman, succumbs to the slave life to save her own skin. The juxtaposition of the poor 20th Century Dana, basically working as slave-labor for the “casual labor agency” (Butler 52), with the 19th Century Dana, working as an actual slave for the Wainwright plantation, offers interesting insights into Dana’s personality as well as the relationship between the agency and the plantation. How much better is 1976 America compared to the dismal, abysmal 1815 Southern America? Are blacks treated any better a hundred fifty years later? Through Dana’s story, I was more inclined to answer in the negative. While blacks are not the only group of people working in the agencies in the 1970s, they constitute a large number of the workers. The conditions these people work in, while maybe slightly better than those of slavery, are certainly sub-human; no one deserves to work in those settings. Dana’s poverty ends when she meets her husband, Kevin, a white man struggling to be an author. Dana (ironically also a writer after she leaves the agency), through her love for Kevin and his love for her, escapes her woes and poverty and leads quite a successful life in the 20th Century. When she loses herself to the Antebellum South, accidentally bringing Kevin along with her, she experiences the hardship of having a mixed marriage in a setting where slavery is accepted. The woes experienced by Dana and Kevin while living in the past help them in the end to come closer together in their love for each other. Dana forges her identity through what happened in the past. As a “coming generation” (Gibran), Dana experiences poverty, thereby finding equality with her fellow workers and fellow slaves, and also through the various hardships, rediscovers her love for her husband, Kevin. Harry Jaffa’s account of the Lincoln-Douglas debates allows us as readers to delve into the mind of Abraham Lincoln, discovering his wiles and ways in regards to the Civil War and his views on slavery. While Lincoln was certainly not black, he was born to a very poor family and lived out his life with the bare minimum. He understood how hard it would be for the blacks to move up in society if indeed they ever achieved freedom. Through his own poverty, Lincoln reaches an equality of understanding with the blacks. Lincoln himself states his “eternal fidelity to the just cause, as [he deems] it, of the land of [his] life, [his] liberty, and [his] love…” (Jaffa 43), and when such a man confesses such unconditional love of an idea, an ideal, or a cause, he “choose[s] nobly to oppose the ‘tide’ of events” (Jaffa 43). Nonconformism breeds change, and so Lincoln takes a mighty step by going against the flow of events and choosing to oppose slavery. From slavery, the unconditional love of the idea of freedom is born, and Lincoln drives hard with his campaign of universal freedom throughout the United States. “Equality through poverty” and “love from woes” are phrases especially poignant to Lincoln, and his leadership role during the Civil War was vital in implementing his ideal cause he held so firmly to. Martin Luther King, Jr., a man of the “coming generation” (Gibran) after the Reconstruction period was long past, once said, “The sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality” (King). He could not have been more right, and while the African-American population of the United States may not have the equality with the whites in as total a way as was imagined, each day brings the gap closer together. While the Civil War might be called the Dark Ages of the United States for the African-American population, they pulled through and have made it to the other side, and I predict a Golden Age for the African-Americans within the near future. Works Cited Butler, Octavia. Kindred. 25th Anniversary Ed.. Boston: Beacon Press, 1979. Fast, Howard. Freedom Road. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1995. Gibran, Kahlil. "Kahlil Gibran Quotes." Brainy Quote. 2007. Brainy Quote. 30 Nov 2007 <http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/k/kahlilgibr101593.html>. Jaffa, Harry V.. A Crisis of the House Divided: An Interpretation of the Issues in the Lincoln-Douglas Debates. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982. King, Jr., Martin Luther . "Martin Luther King, Jr. Quotes." Brainy Quote. 2007. Brainy Quote. 30 Nov 2007 <http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/m/martinluth162495.html>.