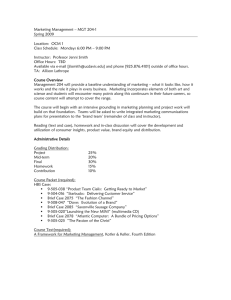

The Role of Visuals in Defining Fashion Lifestyle Brand Identity

advertisement