PDF copy of the chapter

advertisement

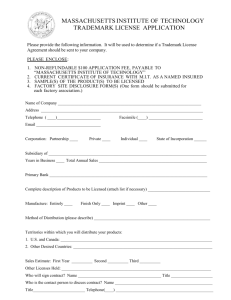

3 TRADEMARKS IN FILM, TELEVISION, WEBCASTS, VIDEO GAMES AND SONGS (JANUARY 3, 2014) Mark V.B. Partridge Daniel L. Rogna Partridge IP Law If you find this article helpful, you can learn more about the subject by going to www.pli.edu to view the on demand program or segment for which it was written. 129 130 INTRODUCTION1 A. The use of trademarks in entertainment reveals a tension between the desire to prevent consumer confusion and protect goodwill on one hand and the desire to give great latitude to artistic expression and noncommercial speech. Brand owners may desire a monopoly but that is not what the law allows. Not all uses of another’s trademark infringe. The tension between trademark protection and free speech is sometimes resolved using a traditional infringement analysis: in context if there is no likelihood of confusion there is no infringement. In other cases, the courts give added weight to the free speech interest. At the extreme, some courts have found infringement claims to be barred by the free speech interest. Recent developments in the fields of film, television, video games and songs are discussed below. B. FILM Use of trademarks in film is largely protected by the First Amendment. Despite recent trends surrounding product placement, discussed further below, “[t]he fact that [companies] can pay for control doesn’t mean they have the right to control,” the use of their marks in film. Priska Neel, Is That A Budweiser In Your Hand?: Product Placement, Booze, And Denzel Washington, NPR: Monkey See (Nov. 27, 2012), http://www.npr.org/blogs/ monkeysee/2012/11/27/165989232/is-that-a-budweiser-in-your-handproduct-placement-booze-and-denzel-washington (quoting Daniel Nazer). Take, for example, the “George of the Jungle 2” case. Caterpillar v. Walt Disney Studios, 287 F. Supp. 2d 913 (2003). There, Caterpillar sued Disney for unauthorized use of genuine Caterpillar bulldozers bearing trademarks on them with no apparent alterations. Caterpillar’s concern was not just that the marks were used without authorization in the film, but that those bulldozers were used to tear down the rainforest and were visible for eight of the film’s eighty-seven minute run time. The court found for defendant Disney, stating that the appearance of well known trademarks in cinema and television is a common phenomenon. Id. at 919. The court first found that there was no trademark infringement because Disney did not intend “to free ride on the fame of Caterpillar’s trademarks to spur the sales and awareness” of its movie, and “it appears unlikely . . . that any consumer would be more likely to buy or watch ‘George 2’ because of any mistaken belief that Caterpillar sponsored this 1. Mark V.B. Partridge is the Managing Partner of Partridge IP Law. Daniel L. Rogna is an associate with the firm. 3 131 movie.” Id. at 920. Second, the court concluded that no trademark dilution was likely because “nothing in [the film] even remotely suggest that Caterpillar products are shoddy or of low quality,” noting that Disney did not anthropomorphize the machines but rather made them the “inanimate implements” of the villain’s schemes. Id. at 923. This ruling is typical of cases involving trademark infringement in film. For example, the misuse of a Slip-n-Slide toy in the movie Dickie Roberts: Former Child Star led to a suit against the film’s producers, claiming unauthorized use and blurring. Wham-O, Inc. v. Paramount Pictures Corp., 286 F. Supp. 2d 1254 (N.D. Cal. 2003). The Wham-O court denied the request for a temporary restraining order, finding that it was obvious that the Slip-n-Slide was being misused. Similarly, Hormel, the producer of Spam, sued Jim Henson Productions over the creation of a puppet named Spa’am. Hormel Foods Corp. v. Jim Henson Prods., 73 F.3d 497 (2d Cir. 1996). There, the court concluded that, “[t]here is very little likelihood that Henson’s parody will weaken the association between the mark SPAM and Hormel’s luncheon meat. Instead, like other spoofs, Henson’s parody will tend to increase public identification of Hormel’s mark with Hormel.” Id. at 506. “In Hormel, Wham-O, and Caterpillar the courts expressly noted that moviegoers-even children-would understand that the marks were being depicted to achieve a humorous effect, and since they realize the fantastical nature of the genre, they would not be deceived into believing the plaintiffs endorsed the movies in which their marks appeared.” Robert C. Welsh and Pratheepan Gulasekaram, Protecting Products that Go Hollywood, Daily Journal MCLE, http://www.dailyjournal.com/ cle.cfm?show=CLEDisplayArticle&qVersionID=133&eid=589011& evid=1. In November 2012, Anheuser-Busch asked Paramount Picture Corp. to obscure or remove all Budweiser logos from the Denzel Washington film Flight. See Budweiser Seeks Removal of its Logo from ‘Flight’, Entertainment Weekly (Nov. 6, 2012), http://insidemovies.ew.com/ 2012/11/06/flight-budweiser-denzel-washington/. Anheuser-Busch did not grant permission for the use of Budweiser products in the film and was concerned with the negative implications of Budweiser in the film. In contrast, Heineken signed a $45 million partnership to have its beer featured in the most recent James Bond movie, Skyfall. Neel, Is That Budweiser, NPR. Flight depicts beer in a negative light, and Skyfall depicts it positively. From the trademark owner’s perspective, it is understandable why in one case you would want to get your mark in to a movie, and in the other you would want to get it out. How the product is 4 132 portrayed makes a huge difference for trademark owners, but it does not require film makers to seek consent for every use of a mark in a film, as discussed above. However, the fact that any company would be willing to pay such a substantial sum as Heineken raises the possibility that consumers may not be able to tell the difference. As Mark Partridge suggested, “with the explosion of product placement in recent years, a company might try to make an argument that by the brand appearing in a film, the audience assumed it had granted permission.” Budweiser Seeks Removal, Entertainment Weekly. However, there is an inconsistency inherent in a plaintiff alleging both confusion and tarnishment claims. If a trademark is placed in a negative context through a defendant’s depiction, the reasonable consumer is correspondingly less likely to be fooled into thinking that any trademark owner would sponsor or endorse such a negative portrayal. See Mattel, Inc. v. MCA Records, Inc., 296 F.3d 894 (9th Cir. 2002), cert. denied, 537 U.S. 1171 (2003). Regardless of this conundrum, the continued use and enhanced visibility of product placement in films raises the concern that consumers will be confused by any use of a trademark in film, whether it is a positive or negative depiction. So, although the law currently favors the use of marks as artistic expression, there is potential for change. Parody raises interesting issues, as discussed in Anthony V. Lupo and Anthony D. Peluso, A Survey of the Case Law On Copyrights snd Trademarks in Film snd Television: Part II, Bloomberg Law (2012), http://about.bloomberglaw.com/uncategorized/copyrights-andtrademarks-in-film-part-ii/: [I]n GTFM, LCC v. Universal Studios, Inc., the plaintiff brought trademark infringement and dilution claims against the defendant for its parodic use of the plaintiff’s registered mark FUBU (i.e., “For Us, By Us”) in its film How High. Rather than displaying FUBU, the film’s protagonist wore a t-shirt with the mark “BUFU,” which, according to the protagonist, stood for “By Us, F*** You.” In granting summary judgment in favor of the defendant, the SDNY ruled that its use of the mark was intended to be a parody, “entitled to the full protection under the First Amendment,” as indicated by the parody’s similarity to the original mark and the film’s comedic context. The court further reasoned that the defendant “was not acting as a competitor of plaintiff’s by attempting to sell products or services under the name ‘BUFU,’” which was important because “[i]n trademark infringement cases, parodies are protected where the mark is being used to lampoon or comment upon the trademark owner or the mark itself, in which expression, and not commercial exploitation of another’s trademark, is the primary intent, and in which there is a need to evoke the original work being parodied.” Finally, the court rejected the plaintiff’s dilution argument because its “FUBU marks appear nowhere in the film, and thus, 5 133 plaintiffs have no claim that FUBU was used in a manner injurious to the mark and to its reputation and good will.” C. TELEVISION 1. Product Placement “Consumers who watch television sitcoms and see product placements through covert marketing have better memories of the products and better attitudes toward the brands, according to three joint studies led by the University of Colorado Boulder.” Covert product placements in TV shows increase consumers’ memories and brand attitudes, says CU-Boulder study, University of Colorado Boulder (Sept. 23, 2013), http://www.colorado.edu/news/releases/2013/09/23/ covert-product-placements-tv-shows-increase-consumers%E2%80% 99-memories-and-brand. However, disclosure of paid product placements “decreased the influential effects, especially when the disclosure occurred after the consumer was exposed to the marketing.” Id. This study comes only a few months after the General Accountability Office “urged the Federal Communications Commission to revise standards for disclosing TV product sponsorships . . . for product placement,” noting that “FCC guidance for the sponsorship identification requirements has not been updated in nearly 50 years” and that the FCC’s 1992 revisions provided “little useful information.” FCC Urged to Revise Standards for TV Product Disclosure, The Wrap (Feb. 28, 2013), http://www.thewrap.com/tv/article/fcc-urgedrevise-standards-tv-product-disclosure-79751. This report was requested in January 2013 by House Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi and Rep. Henry Waxman, who “questioned whether DVR and commercialskipping were prompting sponsors to switch to alternative forms of advertising that wasn’t always being fully disclosed.” Id. A major concern is the extent to which consumers are unaware of “embedded advertising.” Currently, “[f]or commercial content, such as advertisements, embedded advertisements, and video news releases, the [disclosure of content aired in exchange for money, services, or other inducement] must be aired when the content is broadcast and can be either a visual or an audible announcement.” Gov’t Accountability Office 13-237, Broadcast and Cable Television, at 6-7 (January 2013). Ultimately, the GAO recommended an update of the law to reflect current technologies. Id. at 31. The GAO Report explores 6 134 what kind of embedded advertisements may or may not require sponsorship disclosure: a sponsorship announcement is not required every time a product appears in a program. For example, FCC’s guidance describes scenarios in which a manufacturer provides a car to a television show for a detective to chase and capture the villain, and states that the use of the car alone would not require a sponsorship announcement. In this scenario the use of the car could be considered “reasonably related” to its use in the show. However, in the same scenario, if a character also made a promotional statement about the specific brand—such as its being fast—FCC requires a written or verbal sponsorship announcement sometime during the program. According to FCC’s guidance, in this second scenario, the specific mention of the brand may go beyond what would be “reasonably related” to its use in the show. Id. at 10-11. These examples reveal subjective line between what does and does not require disclosure. I would argue that today’s producers and companies would prefer the “reasonably related” option as a vehicle to advertise products. For example, compare recent episodes of FOX’s sitcom “New Girl,” both using Ford SUV’s. First, in the October 23, 2012 episode “Models,” main character Jess must fill in for her friend Cece, a model, who is unable to do her job of modeling with a new Ford SUV. Not only does Jess appear on a rotating stage with the Ford, a Ford executive discusses talking points about the new car throughout that minute of the show. “The dialogue on the show during that scene was literally written by the Ford Motor Co.” Ford product placement runs over episode of Fox’s ‘New Girl’, The L.A. Times (Oct. 29, 2012), http://articles.latimes.com/2012/oct/29/entertainment/la-et-ct-fordnew-girl-promo-20121029. Arguably, this goes beyond what is “reasonably related” to use in the show, despite the Ford being specifically worked in to the plot of the episode. So, it would require a sponsorship announcement. In contrast, a Ford appears in both the April 4, 2013 “First Date” and November 12, 2013 “Menus” episodes. In both episodes, the characters utilize the Ford’s “hands-free liftgate” technology, in which an individual can tap the underside of the car’s rear fender to automatically open the trunk. In both episodes, the characters have objects in their hands and “need” to utilize the technology to open the trunk without their hands. See Product Placement: The TV Ads Consumers Can’t Skip Or Hop, Marketing Land (May 28, 2013), http:// marketingland.com/product-placement-tv-ads-45729. These episodes almost perfectly recreate the Ford commercials themselves. See, e.g., 7 135 Ford Escape Hands-Free Liftgate Commercial, YouTube (Aug. 29, 2012), http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I1V_rm645S0. In the second set of episodes, the use of the Ford is arguably “reasonably related” to the plot of the episodes and arguably would not require disclosure by FOX of the paid endorsement. The point is not to call out FOX or “New Girl” for use of embedded advertisements, but rather to show how arbitrary the current guidelines regarding such advertisements can be. In a time when commercials are being skipped with greater frequency, producers will look to integrated advertisement as a method to maintain revenue streams from big budget advertisers. Even if producers and networks do disclose these advertisement, how much use is it to the consumer if the disclosure comes in rapidly scrolling credits at the end of a TV show? Eric Goldman, Think You Want To Be Told About Product Placements In Movies? Think Again, Forbes (July 9, 2013), http://www.forbes.com/sites/ericgoldman/ 2013/07/09/think-you-want-to-be-told-about-product-placements-inmovies-think-again-2/. This developing area is of great importance to trademark law in entertainment because product placement is significantly more commercial than the artistic, protected speech that trademarks are otherwise used for in various media. 2. Reality Television Reality TV adds a wrinkle to this situation. In 2011, retailer Abercrombie & Fitch offered “Jersey Shore” cast member Mike “The Situation” Sorrentino cash to stop wearing its clothing and introduced its own line of clothing – “Fitchuation” – seemingly as a way to mock him. In response, Sorrentino filed a $4 million lawsuit alleging trademark violations, deceptive advertising and misappropriation of his publicity rights. A Florida court eventually found for Abercrombie and Fitch. Eriq Gardner, ‘Jersery Shore’ Star Loses ‘Fitchuation’ Lawsuit to Abercrombie & Fitch (July 3, 2013), http://www. hollywoodreporter.com/thr-esq/jersey-shore-abercrombie-fitch-situationlawsuit-273667, and http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/thr-esq/jerseyshore-star-loses-fitchuation-579759. For some trademark owners, the concern may that that the public will falsely believe that a reality “star” is endorsed by the company to wear or use a certain product. As in the Abercrombie & Fitch situation, the company will be concerned with a sullied public impression of its mark and goods because of unwanted use in a reality show. 8 136 D. VIDEO GAMES The seminal case for trademark use in video games is the Grand Theft Auto case. E.S.S. Entertainment 20002, Inc. v. Rockstar Videos, Inc., (9th Cir. 2008). In that case, the court found that Rockstar’s use in its vide game of the virtual strip club the “Pig Pen” did not infringe E.S.S.’s trademarks for its flesh and blood strip club the “Play Pen.” Because Rockstar’s use was artistically relevant to creating a look and feel of East Los Angeles and there was no likelihood of confusion, the court found that Rockstar’s use was acceptable under the Rogers test. More recently, game producer Zynga has filed suit against another app maker for use of “With Friends.” Shawn Knight, Zynga Files Suit Against Bang With Friends over Trademark Infringement, TechSpot (July 31, 2013), http://www.techspot.com/news/53452-zynga-files-suitagainst-bang-with-friends-over-trademark-infringement.html. Zynga, the maker of the widely popular “Words with Friends” game, took umbrage when a new app called “Bang With Friends” was introduced. Billed as a service that allows users to anonymously hook up with their Facebook friends, “Bang With Friends” upset Zynga not because of the racy content, but because of the exploitation of its trademark. The case eventually settled, and Bang With Friends stated that “[a]lthough he terms of the settlement are confidential, Bang With Friends Inc. acknowledges the trademark rights that Zynga has in its with friends marks and will be changing its corporate name and rebranding its services in the near future.” Karen Gullo, Zynga Settles Trademark Suit Against ‘Bang With Friends’, Bloomberg Technology (Sept. 30, 2013), http://www. bloomberg.com/news/2013-09-30/zynga-settles-trademark-suit-againstbang-with-friends-.html. In contrast to E.S.S., “Bang with Friends” seemed to clearly free ride on the goodwill of Zynga’s “With Friends” mark. Consumer confusion was likely and certainly could have led to tarnishment of Zynga’s reputation for family-friendly games. E. MUSIC The “Barbie Girl” case is important not just for its application to entertainment law but for the protection of artistic free speech rights. Mattel, Inc. v. MCA Records, Inc., 296 F.3d 894 (9th Cir. 2002), cert. denied, 537 U.S. 1171 (2003). Mattel’s claim was based on the blurring of its mark from use by Aqua in its song “Barbie Girl,” which characterized Barbie as a bimbo and sex object. Judge Kozinski determined that the 9 137 song was protected as parody under the doctrine of nominative fair use and the First Amendment. Essentially, it was not likely that consumers would confuse the song with Mattel’s Barbie doll. Rather, the song made a social comment about the Barbie doll as a figure, which was protected as fair use. F. INTERMEDIARIES Aside from the “safe harbor” of the First Amendment for creative expression, courts have also recognized a safe harbor for intermediaries. A leading example is Tiffany, Inc. v. eBay, Inc., 600 F.3d 93 (2d Cir. 2010), in which the jeweler brought suit against the online marketplace for trademark infringement, trademark dilution and false advertising in response to counterfeit products being sold through defendant’s website. The Second Circuit held in part that eBay was not liable for contributory trademark infringement because Tiffany failed to show that eBay had more than a general knowledge that its services were used to sell counterfeit goods. Id. at 107, citing Inwood Laboratories Inc. v. Ives Laboratories, Inc., 456 U.S. 844 (1982). Further, eBay was not wilfully blind to the infringing activity and took active steps to prevent the sale of counterfeit products, including the removal of potentially counterfeit listings. Tiffany, 600 F.3d at 110. So, the courts have created a safe harbor for intermediaries from trademark infringement claims that mirrors the safe harbor provision from copyright infringement under the DMCA. See 17 U.S.C. § 512. Trademark owners must police their own marks and when appropriate, an intermediary must actively stop trademark infringement occurring on its site. This raises the question of what other laws may provide safe harbor provisions for unfair competition and trademark infringement actions. The Communications Decency Act (“CDA”), 47 U.S.C. § 230(c)(1), provides that “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” This provision has been used to protect intermediaries from defamation and criminal claims. See, e.g., Chi. Lawyers’ Comm. for Civ. Rights Under Law, Inc. v. Craigslist, Inc., 519 F.3d 666 (7th Cir. 2008) (finding that Craigslist was protected by the safe harbor of the CDA from postings that violated the Fair Housing Act because Craigslist transmits, not publishes, third party content); Hollis v. Cunnignham, Case No. 2007-cv-23112 (S.D. Fla. 2007) (website 10 138 “www.dontdatehimgirl.com” applying CDA safe harbor as a defense to defamatory content posted by users) . However, it is questionable whether these CDA protections extend to intellectual property infringement. See, e.g., Gucci Am., Inc. v. Hall & Assocs., 135 F. Supp. 2d 409 (S.D.N.Y. 2001) (finding that no immunity for contributory liability for trademark infringement exists under the CDA). G. CONCLUSION The analysis of current cases concerning the use of trademarks in entertainment media involves consideration of several key principles. First, trademarks are not a monopoly right or a right in gross. The law does not permit the brand owner to control all use of its mark; only those uses that are infringing. Second, if the defendant’s use of the mark is for the purpose of selling a product or service, it is unlikely to receive any heightened free speech protection and is likely to be subjected to a traditional trademark likelihood of confusion analysis. Third, if the defendant’s use of the mark is for the purpose of artistic expression, it is likely to received added First Amendment protection and therefore less likely to be considered an infringement. In some cases, the First Amendment interest may be sufficient to bar relief. Finally, the evolving nature of brand placement and sponsorship may in the future alter consumer perceptions about the brand owner’s relationship to the appearance of the mark in entertainment media. If the public comes to believe that the appearance of a mark in entertainment media is indeed controlled by the brand owner then the Courts may follow by more readily finding a likelihood of confusion as a result. That potential is suggested by the trends discussed above, but is not yet prevalent in the issued decisions. 11 139 NOTES 140