Cadbury Schweppes and beyond: the future of the UK CFC Rules

advertisement

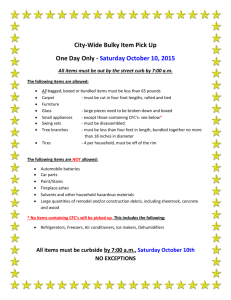

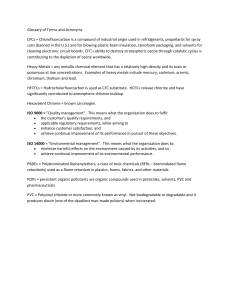

Cadbury Schweppes and beyond: the future of the UK CFC Rules Richard Wellens 25 years after the introduction of the UK’s Controlled Foreign Companies (CFC) legislation, this paper reviews its core principles, before examining the impact on the CFC rules of the Cadbury Schweppes 1 decision in the European Court of Justice (ECJ) and the Vodafone 2 2 case in the domestic courts. It then concludes by examining the likelihood of the CFC rules surviving in their current form for another quarter century. 1. History of UK CFC legislation The abolition of exchange controls in the UK in 1979 was seen to give UK resident companies the opportunity to divert and accumulate profits in so‐called tax havens and/or lower tax jurisdictions 3 ; profits which would otherwise have been subject to tax in the UK. In response to this perceived abuse of the relaxation of the exchange control system, the Inland Revenue (now Her Majesty’s Revenue & Customs or HMRC) issued a consultative document in 1981 on the introduction of proposed CFC legislation in the UK. The CFC rules were finally introduced in the Finance Act 1984, ultimately taking their place in ss. 747‐756 and sch. 24‐26 of ICTA 1988 4 . The CFC legislation was designed to bring within the charge to tax the activities of captive insurers, “dividend trap” companies and “money box” companies 5 ; it was not intended to catch UK resident companies with ordinary overseas trading activities, and, therefore, where the legislation classified a company as a CFC, it then provided certain carve outs to exempt otherwise eligible companies from incurring a CFC charge. 2. Principles of UK CFC legislation At a fundamental level, the UK CFC rules pose three questions about the characteristics of a company to determine whether or not it is a CFC. 2.1. Key characteristics Residence 1 Cadbury Schweppes plc, Cadbury Schweppes Overseas Ltd v Commissioners of Inland Revenue C‐ 196/04 [2006] ECR I‑7995 2 Vodafone 2 v The Commissioners of Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs [2008] EWHC 1569 (Ch) 3 Bramwell, Richard; Hardwick, Michael; James, Alun & Kingstone, Mark (Bramwell et al.): Taxation of Companies and Company Reconstructions. Sweet & Maxwell, 1999, p.483 4 Income and Corporation Taxes Act 1988 5 Bramwell et al., op. cit., p.483 CFC legislation only applies to companies which are not resident in the UK and if this is the case, then the next test is applied. Control In order for a non‐UK resident company to be considered to be a CFC, it must be controlled by UK residents. Subsequent revisions to the CFC legislation have to a certain extent widened the definition of control, but it was originally defined as 51% or more of those with interests in the company being resident in the UK 6 . An interest may be defined, inter alia, as share capital, voting rights or the right to receive distributions 7 . Lower level of taxation The original CFC legislation considered a lower level of taxation to be anything below 50% of the ‘corresponding UK tax’; this was increased to 75% in 1993 8 . In the event that the residence, control and lower level of taxation tests are met, the company in question will be considered to be a CFC for UK purposes. There is then a list of tests which can be applied to exclude the CFC from a charge to UK tax. 2.2. Exclusions De minimis If the profits earned in the CFC are less than £50,000 and therefore considered to be de minimis, no CFC charge arises. Acceptable distribution policy (ADP) A CFC which distributes to UK residents within an 18 month timeframe not less than 90% of its available profits within an accounting period is deemed to have made an acceptable distribution and its UK resident shareholders are not subject to a CFC charge 9 . Public quotation condition An exclusion which was repealed in the Finance Act 2007, the public quotation condition excluded from the CFC legislation companies in which at least 35% of the voting shares were held in the public domain and traded on recognised stock exchanges 10 . Exempt activities 11 This exclusion is designed to carve out from the CFC legislation those entities which can be reasonably regarded as carrying out business activities overseas where the main purpose is not to reduce UK tax. The legislation contains a 6 ICTA 1988, s. 756 (3). As referenced in Tiley, John: Revenue Law. Hart Publishing, 2008, p.1177 ibid. 8 ICTA 1988, s. 750, as amended by FA 1993, s 119(1) & (2), in Tiley, op. cit., p.1178 9 ICTA 1988, sch. 25, paras 1‐4 10 ICTA 1988, sch. 25, para 13 (2), as repealed in Finance Act 2007. 11 As defined in ICTA 1988, sch. 25, paras 5‐12 7 ICTA 1988, s. 749B (1), (3) & (4), in reasonably prescriptive set of conditions which need to be met to fall into this category. Motive test 12 A company which does not satisfy any of the above tests may still be exempt from the CFC charge if it meets the motive test. This can be split into three main tests 13 : · The reduction in UK tax is minimal; or · The main purpose of the CFC is not to reduce UK tax payable; and · The main reason for the existence of the company is not to reduce or divert profits from the UK Excluded countries In addition to these exclusion tests, a list of countries to which the CFC rules do not apply either in full or in part has been published in the form of a statutory instrument 14 . Where none of these exclusions apply, a CFC charge is levied if the profits of the CFC apportioned to the UK resident company exceed 25% of the CFC’s total chargeable profits. In short, the UK CFC legislation can be summarised at a very high level by asking the following questions 15 : · Is the company resident outside the UK? · Is it controlled by UK residents? · Is the local tax less than 75% of the UK tax? If so, the company in question is a CFC unless it can apply one of the above mentioned exclusions. Where this is not the case, there is a UK tax charge on the profits of the CFC which are apportioned to the UK resident deemed to control the non‐resident company. 3. UK CFC legislation in the dock With the exception of ABTA v IRC 16 , in which the motive test exclusion within the CFC legislation was tested (and in which the Special Commissioners found that ABTA did not meet the requirements of the exclusion provided for under the 12 ICTA 1988, s. 748 (3) 13 Bramwell et al., op. cit., p.485 14 The Controlled Foreign Companies (Excluded Countries) regulations 1998 (SI 1998/3081) 15 Bramwell et al., op. cit., p.485 Association of British Travel Insurers v Inland Revenue Commissioners, SpC 359 (2003) STC (SCD) 194 16 motive test) the first key challenge to the UK’s CFC legislation came in the form of Cadbury Schweppes 17 . In 1987, the Irish government established the International Financial Services Centre (IFSC) in Dublin to encourage investment in the region. Qualifying companies 18 which established operations in the IFSC benefited from a corporation tax rate of 10% 19 . Cadbury Schweppes plc incorporated two new entities in the IFSC; Cadbury Schweppes Treasury Services (CSTS) and Cadbury Schweppes Treasury International (CSTI). These entities were established with the business purpose of raising and providing finance for the Cadbury Schweppes group. 4. The view of the domestic courts As recorded in the UK Special Commissioners’ order of reference 20 to the ECJ, the Inland Revenue believed that these newly established group companies served to replace existing corporate structures within the Cadbury Schweppes group, and were established in Ireland solely to benefit from the IFSC tax regime for group treasury companies, such that the profits generated would not be taxed in the UK 21 . The Inland Revenue asserted that neither CSTS nor CSTI met any of the exclusion tests contained in the CFC legislation 22 . Of particular relevance, it concluded that the main purpose of CSTS and CSTI was to achieve a reduction in UK tax and that if the companies had not existed, their profits would have been taxable in the UK, and therefore the Irish companies also failed the motive test in the CFC legislation 23 . Accordingly, the Inland Revenue regarded these entities as CFCs and raised a corporation tax assessment against the first UK resident company in the ownership chain, Cadbury Schweppes Overseas Limited in the amount of £8.6m (profits in Ireland were £34.6m, on which UK corporation tax at 33% was levied in the amount of £11.4m, less Irish tax paid of £2.8m). 17 There is a large body of material on the Cadbury Schweppes case. For a detailed discussion of the Cadbury Schweppes case, see, in particular, O’Shea, Tom: The UK’s CFC rules and the freedom of establishment: Cadbury Schweppes plc and its IFSC subsidiaries – tax avoidance or tax mitigation? EC Tax Review, 2007‐01, pp.13‐33 18 For example, banking operations, specialised insurance companies, fund management companies and corporate treasury services. 19 As legislated in the Finance Act 1987. This rate increased for newly incorporated companies to the standard corporation tax rate in Ireland of 12.5% in 2002 with grandfathering provisions for existing entities. Since 2006, all companies in the IFSC have been subject to the standard corporation tax rate. 20 SpC 415, issued 1 June 2004. As referenced at: www.financeandtaxtribunals.gov.uk (last visited 3 March 2009) 21 This is also cited as being common ground in para 18 of Cadbury Schweppes, although this fact was disputed by Cadbury Schweppes in schedule 3 of the decision on application for direction, SpC 512 22 Schedule 7 (1) – (4) in the order of reference, SpC 415 23 Schedule 7 (5) in ibid. Cadbury Schweppes appealed the assessment to the Special Commissioners, claiming that the application of a CFC charge was in direct breach of the freedom of establishment in Article 43 of the EC Treaty, of the freedom to provide services under article 49 and the freedom of movement of capital under article 56. The Special Commissioners considered a number of issues to be sufficiently uncertain as to warrant guidance from the ECJ, including: 24 · Was the use of Ireland to benefit from a preferential tax regime a legitimate application of the freedom of establishment, or an abuse of that freedom? · Is the UK’s CFC legislation discriminatory or merely restrictive? · In terms of being restrictive, is it relevant that the rules for calculating the tax payable by CSTS and CSTI are different from those which would be used for a UK resident subsidiary, and that there is no group relief available for the Irish resident entities? · When determining discrimination, what comparison should be made? Is the comparator a UK plc establishing a subsidiary in the UK, or one establishing a subsidiary in a non‐low tax jurisdiction · Whether or not the restriction/discrimination can be justified on the basis of preventing tax avoidance and whether or not the legislation (in particular the motive test element) is proportionate in achieving that aim. With these points in mind, the question referred to the ECJ by the Special Commissioners was the following: “Do articles 43, 49 and 56 of the EC Treaty preclude national tax legislation such as that in issue in the main proceedings, which provides in specified circumstances for the imposition of a charge upon a company resident in that Member State in respect of the profits of a subsidiary company resident in another Member State and subject to a lower level of taxation?” 25 5. Advocate General Léger’s opinion The Advocate General (AG) concluded that the UK CFC rules were compatible with articles 43 and 48 of the EC Treaty, in situations where “that legislation applies only to wholly artificial arrangements intended to circumvent national law” 26 . He based this conclusion on three separate streams of analysis 27 : 24 Schedule 10 in ibid., and also O’Shea, op. cit., p.14 Cadbury Schweppes 26 See para 151 of Advocate General Léger’s opinion (the “Opinion”) 27 See para 38 of the Opinion 25 See para 28 of · Did the establishment by Cadbury Schweppes of the Irish subsidiaries in order to take advantage of a more favourable tax rate in Ireland constitute an abuse of the freedom of establishment? · If not an abuse, did the UK’s CFC rules restrict the freedom of establishment? · If the rules were restrictive, could they be justified? 5.1. Abuse of the freedom of establishment The AG began by arguing that the establishment of a company to benefit from a more favourable tax regime in another member state is not, in itself, an abuse of the freedom of establishment 28 . He went on to say that “it is the exercise of economic activity in the host Member State which is the raison d’être of establishment” 29 . The AG cited 30 the ECJ jurisprudence in Centros 31 and Inspire Art 32 , both cases in which companies chose to establish themselves in the UK to avoid the otherwise greater regulatory burden in Denmark and the Netherlands respectively, and where the refusal to acknowledge this incorporation was held as contrary to the freedom of establishment. He inferred from this case law that when the objective pursued by the freedom of establishment has been fulfilled, the motivation behind the exercise of that freedom cannot be a reason for not affording the protection guaranteed under the EC Treaty 33 . In the context of alignment of the member states’ tax systems, the AG concluded that since there is no harmonisation of direct taxes at the Community level, it must be accepted that there will be a certain degree of competition between the tax systems of the member states. However, the AG stressed that this is a political matter and does not impact on the rights conferred on companies exercising their right to freedom of establishment 34 . On the basis of these arguments, the AG concluded that the establishment of the Irish subsidiaries by Cadbury Schweppes in order to benefit from a more attractive tax regime does not, in itself, constitute an abuse of the freedom of establishment 35 . 5.2. Restriction on the freedom of establishment 28 See para 40 of the Opinion 29 See para 42 of the opinion 30 See paras 44‐48 of the Opinion 31 Centros Ltd v Erhvervs­ og Selskabsstyrelsen, C‐212/97 [1999] ECR I‐1459 32 Kamer van Koophandel en Fabrieken voor Amsterdam v Inspire Art Ltd, C‐167/01 [2003] ECR I‐ 10155 33 See para 49 of the Opinion 34 See paras 55 & 57 of the Opinion 35 See para 60 of the Opinion Having concluded that there was no abuse of the freedom of establishment, the AG then went on to analyse whether or not the UK CFC rules constituted a restriction on the freedom of establishment. Submissions from various governments of the member states supported the argument that the UK CFC legislation is not discriminatory, because the additional tax charged puts the parent company and its subsidiaries economically in the same position as if the subsidiaries had been incorporated and tax resident in the UK, and therefore the legislation is fiscally neutral 36 . The AG rejected these arguments on the basis that i) the legislation applied only to subsidiaries established in “low tax” jurisdictions and ii) the parent company is potentially taxed on the profits in the subsidiary at the moment they arise. The AG regarded these features of the legislation as disadvantageous, both in respect of UK parent companies with UK subsidiaries and UK parent companies with non‐UK subsidiaries in non‐“low tax” jurisdictions 37 . The fact that the tax claimed would not be any more than that due if the subsidiaries had been established in the UK “does not eliminate the unequal treatment at the level of the parent companies” 38 , and the AG cited 39 the case law of Eurowings 40 and Barbier 41 in support of this viewpoint. As a result, the AG concluded that the UK CFC legislation constituted a restriction on the freedom of establishment 42 . 5.3. Justification of the restriction The AG accepted that tax avoidance is one of the public interest reasons for which a restriction on the fundamental freedoms can be justified 43 . However, the AG qualified this statement by reaffirming existing case law in which states that: “a hindrance to freedom can only be justified on the ground of counteraction of tax avoidance if the legislation in question is specifically designed to exclude from a tax advantage wholly artificial arrangements aimed at circumventing national law.” 44 In the AG’s view, the legislation in question must be targeted and cannot be used as a blanket method of justifying tax avoidance; it must afford the possibility for a national court to take a case‐by‐case approach to individual situations, when 36 See paras 68‐69 of the Opinion 37 See paras 72‐74 of the Opinion 38 See para 76 of the Opinion 39 See para 82 of the Opinion 40 Eurowings Luftverkehrs AG v Finanzamt Dortmund­Unna, C‐294/97 [1999] ECR I‐7447 The heirs of H. Barbier v Inspecteur van de Belastingdienst Particulieren/Ondernemingen buitenland te Heerlen, C‐364/01 [2003] ECR I‐15013 42 See para 83 of the Opinion 43 See para 86 of the Opinion 44 See para 87 of the Opinion (author’s emphasis) 41 assessing whether or not a taxpayer has employed artificial arrangements to avoid tax and thus should not benefit from Treaty protection 45 . On this basis, the AG outlined a proposed set of objective tests which could be used to ascertain whether or not a transaction is a wholly artificial arrangement intended to circumvent national tax law 46 : · Genuine establishment in the host state. Does the subsidiary have the necessary premises, staff and equipment to carry out the services deemed to be provided to the parent company? · Genuine nature of services provided. What level of competence and control over its activities does the subsidiary’s staff demonstrate? · Value added by the subsidiary. The AG considers that this test could be relevant in establishing the amount of economic substance behind the subsidiary’s activities 47 . The AG accepted that the CFC legislation should be able to presume a certain level of tax avoidance and in so doing shift the burden of proof on to the taxpayer 48 . However, he asserted that it is important for the taxpayer to be able to rebut the presumption of tax avoidance and therefore that the legislation be limited to wholly artificial arrangements 49 . In the context of the UK CFC legislation, it is the ‘motive test’ which must allow for a case‐by‐case analysis of the facts 50 . 5.4. The AG’s conclusions The AG finalised his analysis by concluding that it is not possible to clearly ascertain whether or not the purpose element of the ‘motive test’ enables the taxpayer to exempt itself by proving that the services provided were genuine. Furthermore, the AG did not find it clear whether or not the second part of the test relates to the taxpayer’s subjective motives or if it is enough to prove that the subsidiary is genuinely established in the host state 51 . On this basis, the AG recommended that it is for the national court to decide if the ‘motive test’ can be interpreted in such a way that it is possible to limit its application to artificial arrangements intended to circumvent national tax law 52 . 6. The ECJ’s decision 45 See para 92 of the Opinion 46 See paras 112‐114 of the Opinion It is important to highlight that only the first test outlined in the AG’s opinion subsequently appears in the ECJ’s judgment on the case. 48 See para 136 of the Opinion 49 See para 144 of the Opinion 50 See para 146 of the Opinion 51 See para 149 of the Opinion 52 See para 150 of the Opinion 47 The ECJ followed a similar line of reasoning to that presented by Advocate General Léger, but there were some exceptions. It examined the general concept of establishment and abuse of the freedom of establishment, before ruling on the facts of the case and considering to what extent any restriction on the freedom of establishment can be justified. 6.1. Concept of establishment Although the original question referred by the Special Commissioners also made reference to articles 49 and 56 of the EC Treaty, the ECJ confirmed that the relevant freedom in the case at hand is that of establishment, on the basis that the legislation refers to parent companies in the UK with overseas subsidiaries, over which they have a controlling holding 53 . Furthermore, the ECJ went on to explore what is meant by the concept of establishment. It concluded that the objective of establishment is: “to allow a national of a Member State to set up a secondary establishment in another Member State to carry on his activities there and thus assist economic and social interpenetration within the Community … To that end, freedom of establishment is intended to allow a Community national to participate, on a stable and continuing basis, in the economic life of a Member State.” 54 The ECJ also ruled that the freedom of establishment “presupposes actual establishment … in the host Member State and the pursuit of genuine economic activity there.” 55 6.2. Abuse of the freedom of establishment In the context of what it viewed to be the concept of the freedom of establishment, the ECJ held that, whilst nationals of a member state cannot use Treaty protection as a means of improperly circumventing national legislation 56 , it is settled case law that where a Community national seeks to profit from a tax advantage in another member state, this cannot of itself deprive the national of the rights granted under the EC Treaty 57 . Equally, the ECJ cited Centros and Inspire Art as examples of legitimate regulatory arbitrage between the domestic legislation of two member states and reiterated that such arbitrage does not constitute an abuse of the freedom of 53 See para 32 of Cadbury Schweppes Cadbury Schweppes 55 See para 54 of Cadbury Schweppes 56 See para 35 of Cadbury Schweppes 57 See para 36 of Cadbury Schweppes 54 See para 53 of establishment 58 . As such, Cadbury Schweppes was entitled to rely on the freedom of establishment in the case at hand. 6.3. Restriction on the freedom of establishment On the basis that the ECJ found no abuse of the freedom of establishment, it moved on to examine to what extent the UK CFC legislation represented a restriction on the freedom of establishment. All parties in the case agreed that the CFC legislation conferred different treatment on comparable UK resident parent companies. However, it was the contention of the UK government 59 that UK resident parent companies with CFC subsidiaries paid no more tax than would have been the case if these parent companies had had non‐CFC subsidiaries 60 . This point was argued on the basis that, had the subsidiaries been resident in the UK, they would have paid tax on their profits at the UK corporation tax rate, whereas the CFC legislation sought only to “top up” the amount of tax paid by the parent company to a level equal to that which would have been paid by the group as a whole if the subsidiary had been UK resident. The ECJ rejected this argument entirely. In the view of the ECJ, it is clear from the legislation that the parent of a CFC subsidiary is charged to tax on the profits of another legal entity; a tax charge which is never levied on the parent of a UK resident subsidiary or on that of a subsidiary in a non‐“low tax” jurisdiction 61 . On this basis, the ECJ concluded that the UK CFC legislation does constitute a restriction on the freedom of establishment, stating: “the separate tax treatment under the legislation on CFCs and the resulting disadvantage for resident companies which have a subsidiary subject, in another Member State, to a lower level of taxation are such as to hinder the exercise of freedom of establishment by such companies, dissuading them from establishing, acquiring or maintaining a subsidiary in a Member State in which the latter is subject to such a level of taxation.” 62 6.4. Justification of the restriction The UK government’s justification for its CFC legislation was that it was designed to prevent a specific type of tax avoidance where a subsidiary is established in a 58 See para 37 of Cadbury Schweppes 59 Supported by the Danish, German, French, Portuguese, Finnish and Swedish governments 60 See para 45 of Cadbury Schweppes 61 Ibid. 62 See para 46 of Cadbury Schweppes low‐tax jurisdiction in order to artificially transfer profits from the member state in which they were derived 63 . The ECJ was clear that it was not permitted under the EC Treaty to offset any tax advantage obtained by establishing a subsidiary in a low‐tax jurisdiction by granting less favourable tax treatment of the parent company; prevention of the reduction of tax revenues is not a matter of public policy 64 . In one example of a contrast to the AG’s opinion, the ECJ found that the establishment of a subsidiary in another member state cannot predicate a presumption of tax evasion 65 . However, it qualified this statement by highlighting that a national measure could be justified where it “relates to wholly artificial arrangements aimed at circumventing the application of the legislation of the Member State concerned” 66 . On this basis, and taking into account its view on the concept of establishment, the ECJ concluded that any restriction which is designed to prevent abusive practices must be limited to such situations where i) wholly artificial arrangements are used and there is no economic substance and ii) there is a desire to escape the tax ordinarily due 67 . 6.5. Proportionality of the legislation The ECJ confirmed that the UK CFC rules achieved the objective of preventing tax avoidance in situations where wholly artificial arrangements are put in place (i.e. circumstances in which a restriction would be justified), but it then considered to what extent the legislation goes beyond what is necessary to achieve that purpose 68 . The ECJ ruled that in order to demonstrate a wholly artificial arrangement, it is necessary to consider the subjective factors (i.e. what was the motive behind the establishment of the subsidiary) and also the objective factors – in particular the extent to which the CFC has a physical presence in terms of premises, staff and equipment 69 . In this context, the ECJ included in its judgment only one of the three tests outlined by the AG in his opinion 70 , preferring to set the bar for the level of artificiality quite high with its references to “letterbox” or “front subsidiaries” 71 . 63 See para 48 of Cadbury Schweppes Cadbury Schweppes 65 See para 50 of Cadbury Schweppes 66 See para 51 of Cadbury Schweppes 67 See para 55 of Cadbury Schweppes 68 See paras 59 ‐ 60 of Cadbury Schweppes 69 See paras 64 & 67 of Cadbury Schweppes 70 Namely, physical presence, competence of local employees and value added by the subsidiary 71 See para 68 of Cadbury Schweppes 64 See para 49 of 6.6. Ruling of the ECJ 72 Ultimately, the ECJ referred the matter back to the national court to decide. If the national court can interpret the motive test in the UK CFC legislation as excluding from taxation overseas subsidiaries except in circumstances where wholly artificial arrangements arise, then the UK’s CFC rules are compatible with the freedom of establishment. However, where the motive test has to be interpreted as meaning that: · None of the exceptions to the UK's CFC rules applies; · The intention to obtain a reduction in UK tax is central to the reasons for incorporating the CFC; and · The UK parent company comes within the scope of the CFC rules, despite the absence of objective evidence to indicate that a wholly artificial arrangement exists then the UK CFC legislation must be considered to be incompatible with the freedom of establishment. 7. The UK’s response to Cadbury Schweppes 7.1. Description of the legislation The UK’s response to the ECJ’s ruling was a swift one. The ECJ’s decision was published on 12 September 2006; in the pre‐budget report on 6 December 2006, the UK government introduced s 751A ICTA 1988, which provides for a reduction in chargeable profits for certain activities of business establishments within the European Economic Area (EEA). This reduction is only available to CFCs in an EEA territory which has employees in that territory and in which a UK resident company has a relevant interest 73 . The legislation is not an additional exemption test for EEA resident companies. Rather, it permits EEA resident companies to request from HMRC an adjustment 74 of apportionment to which they are liable under s747(3). In other words, if a company is deemed to be a CFC and does not meet any of the existing exemption tests, the UK resident company that controls it can apply for a reduction (down to zero) of the charge, which would otherwise be apportioned to it. HMRC’s discretion to reduce the apportionment charge is limited to amounts equal to chargeable profits which represent the “net economic value” generated by the “appropriate body of persons” in the CFC through “qualifying work” 75 . 72 See paras 72‐74 of Cadbury Schweppes and O’Shea, op. cit., p.20 73 ICTA 1998, s751A (1), as introduced by sch. 15, Finance Act 2007 74 Ibid., s751A (2) 75 Ibid., s751A (4) “Net economic value” is deemed to exclude any value which derives from the reduction or elimination of any liability of any person to any tax imposed in any territory 76 . The new legislation defines an “appropriate body of persons” as either the CFC itself and persons with an interest in it, or in the case of a group of companies, the CFC and any other person within the group of companies. “Qualifying work” is defined as work carried out within any EEA territory by individuals working for the CFC in that EEA territory 77 . Finally, the legislation stipulates that individuals are only regarded as working for a company in the territory if they are employed by the company in the territory or are otherwise directed by the company to perform duties on its behalf in the territory 78 . Furthermore, the legislation imposes time limits upon UK resident companies with CFCs for claiming a reduction of the apportionment; any claim must be filed before the date on which the company is required to file its tax return for the “appropriate accounting period” 79 . Finally, Schedule 25 of ICTA 1988 was amended to include the definition of “effectively managed” within the EEA as follows: “The condition in paragraph 6(1)(b) 80 above shall not be regarded as fulfilled in relation to a company which is resident in an EEA territory unless there are sufficient individuals working for the company in the territory who have the competence and authority to undertake all, or substantially all, of the company's business.” 81 7.2. Analysis The approach taken by the UK government to its obligation to comply with the ECJ’s ruling in the Cadbury Schweppes case seems to be one of making the bare minimum of changes to the CFC legislation in order to bring it in line with the ECJ’s judgment. The new rules do not represent an additional exemption from the CFC charge and therefore require the UK resident parent company to apply for a reduction in its apportionment after having gone through the process of determining whether or not it does in fact have a CFC. However, since the application for a reduction in the apportioned income has to be made by the date on which it is required to file its tax return for the 76 Ibid., s751A (5), author’s emphasis 77 Ibid., s751A (7) 78 ICTA 1988, s751A (9) 79 ICTA 1988, s751B (2) ICTA 1988, sch. 25, para 6(1)(b), which reads “that, throughout that accounting period, its business affairs in that territory are effectively managed there” 81 ICTA 1988, sch. 25, para 8 (5) 80 appropriate accounting period, there exists the possibility that the company could miss the deadline for filing such a claim whilst it was still waiting to learn whether or not HMRC considered it eligible for one of the existing exemption tests 82 . On the other hand, the legislation makes no provision for HMRC having to respond to applications under s751A(2) within a defined time period. Therefore, whilst waiting to hear of HMRC’s decision on the claim for a reduction in the apportionment of profits, the UK resident company with a CFC may have to make a dividend payment under the acceptable distribution policy in order to ensure that it does not otherwise fall into the CFC legislation 83 . If this is the intended consequence of the legislation, it is clearly trying to act within the letter of the ECJ judgment, rather than its spirit. Furthermore, the legislation introduced in ICTA 1988, s751A/B refers heavily to the physical presence of individuals in the EEA territory, and the implication that an EEA company cannot be effectively managed and controlled unless it has sufficient individuals working in the territory with sufficient competence and authority to undertake the company’s business. As we have seen already, the ECJ judgment in Cadbury Schweppes refers only to genuine economic activity, and it is difficult – at first glance – to see from where the reference to the number of individuals and their level of competence comes. Furthermore, HMRC has already been defeated in the domestic courts on the question of management and control, and competence. In Wood v Holden 84 , a tax structure was established to dispose of shares from one non‐UK resident company to another non‐UK resident company (“Eulalia”, incorporated in the Netherlands) and in so doing avoid any charge to UK capital gains tax. The scheme was devised by an accountancy firm, which subsequently set out the steps to be followed in the scheme. HMRC argued that, since the purchase of the shares by Eulalia was effectively orchestrated by the UK resident accountancy firm advising on the structure, and that the steps required to be executed by Eulalia were minimal, it should be regarded as a UK resident and thus capital gains tax on the disposal would be triggered under the relevant provisions in the UK tax code. The Court of Appeal rejected lower court judgments that Eulalia should be considered as a UK resident, since although the management and control required were minimal, they were still exercised by the directors of Eulalia in the Netherlands. Furthermore, the Court of Appeal made a distinction between the 82 Luder, Sara: PBR 2006: CFCs – Must try harder!, as referenced at www.slaughterandmay.com/media/39015/pbr_2006_‐_cfcs_‐_must_try_ harder.pdf (last visited 7 March 2009) 83 Ibid. 84 Wood and another v Holden (HMIT) [2006] EWCA Civ 26 role of the advisor and the actions taken by the Dutch resident directors of Eulalia and therefore confirmed Eulalia’s residence as being in the Netherlands 85 . The idea that in some way a CFC can only be generating “net economic value” if it has a sufficient number of individuals working for it has a certain Orwellian ring to it; “labour good, capital bad” 86 . This is a surprising distinction, given that the ECJ ruling in response to which this legislation was drafted concerned companies which provided capital in the form of treasury services to the Cadbury Schweppes group, and there was no suggestion in the judgment that certain types of activity are incapable of benefiting from EC Treaty protection 87 . If one analyses the AG’s opinion in the Cadbury Schweppes case, it seems clear that the UK legislators were drafting in response to his three proposed objective tests 88 , and not really focusing on only those elements of the AG’s opinion which were incorporated into the subsequent ruling by the ECJ. This is further evidenced by the relatively short period of time between the ECJ judgment (12 September 2006) and the announcement of the proposed legislation in the pre‐ budget report (6 December 2006). The period between delivery of the AG’s opinion (2 May 2006) and the new legislation appears to be an altogether more likely period over which the new legislation would have been drafted, reviewed and amended in preparation for the pre‐budget report. However, the ECJ ruling does not include these tests in its analysis of what constitutes genuine economic activity; it refers only to “the extent to which the CFC physically exists in terms of premises, staff and equipment” 89 , and therefore the amendments to the CFC legislation would appear to legislate in a way which is inconsistent with the ECJ judgment, preferring instead to take their cue from the AG’s opinion. This over‐reliance on the AG’s list of tests in the new legislation, contrasted against the existing jurisprudence in the UK which is quite clear on the required threshold for “management and control” suggests, at best, a misunderstanding of the interaction between EC and domestic law. As worst, it could be seen as a method of playing off the domestic judiciary against its European counterpart by using ECJ jurisprudence as an excuse for tightening the domestic definition of “management and control”. HMRC may argue that the use of “effective management and control” is consistent with the judgment in Smallwood 90 , but the facts of the case which Nathan, Aparna: Determining company residence after Wood v Holden from http://www.taxbar.com/documents/Company_Residence_Wood_v_Holden_AN_000.pdf (last visited 11 March 2009). 86 Cussons, Peter: Magical mystery tour, or quo vadis?, Tax Adviser – August 2008, p.23 87 Ibid. 88 See paras 112‐114 of the Opinion 89 See para 67 of Cadbury Schweppes 90 Smallwood (trustees of The Trevor Smallwood Trust) v Revenue and Customs Comrs [2008] STC (SCD) 629, 10 ITLR 574. This case centred on the “place of effective management” test in the UK/Mauritius double tax treaty. The UK Special Commissioners found that the change of residence from the UK to Mauritius in the transaction was part of a pre‐ordained set of steps, and 85 prompted the introduction of s751A (i.e. Cadbury Schweppes) lend themselves more towards a Wood v Holden analysis. 8. Vodafone 2 – the death knell for UK CFC legislation? At the same time as HMRC was challenging the CFC position of the Cadbury Schweppes group in Ireland, it was also raising enquiry notices against Vodafone plc in respect of its CFCs in Luxembourg. The outcome of this case could be the final nail in the coffin for the UK’s CFC legislation as it currently stands. 8.1. The facts A UK resident company in the Vodafone group (“Vodafone 2”) had established an overseas subsidiary in Luxembourg (Vodafone Investments Luxembourg SarL – “VIL”) as part of the acquisition of a rival telecommunications company in Germany. The balance sheet of VIL had equity investments of c. €38bn and debt investments of c. €35bn. HMRC contended that the interest income earned by VIL should be apportioned to Vodafone 2 under the UK CFC legislation 91 . As such, upon receiving Vodafone 2 tax return for the period ending 31 March 2001, it raised an enquiry notice. Vodafone accepted that VIL did not fall within any of the usual exceptions as prescribed in the CFC legislation 92 . However, it contended that VIL did meet the requirements of the ‘motive test’ and therefore should not be considered to be a CFC for the purposes of the legislation. Furthermore, Vodafone asserts that s748(3) of ICTA 1988 is not compatible with articles 43 and 48 of the EC Treaty and, as such, should be disapplied 93 . In addition, Vodafone contended that the administrative burden of producing the documentation required to comply with the enquiry notice was contrary to article 43 of the EC Treaty, since it would not have had to shoulder this burden in respect of a UK subsidiary 94 . Therefore, Vodafone applied for an enquiry closure notice to be issued. At an initial hearing, the Special Commissioners confirmed that the enquiry notice had not been properly issued and therefore Vodafone was not obliged to respond to it. They also sought to refer questions to the ECJ. In the interim, the ECJ delivered its verdict on the Cadbury Schweppes case, and the Registrar of the European Court asked the Special Commissioners whether or not they would still like to refer their questions to the ECJ. The Special Commissioners agreed that the submission would be withdrawn, and therefore since the top level management remained in the UK, the place of effective management was always the UK. 91 See para 3 of Vodafone 2 92 See para 9 of Vodafone 2 93 See para 11 of Vodafone 2 94 See para 13(b) of Vodafone 2 would only concentrate on whether or not the CFC legislation was compatible with EC law 95 . The Special Commissioners ruled (on the basis of the Presiding Commissioner’s casting vote) that the motive test in the UK CFC legislation could be interpreted as to apply only to wholly artificial arrangements and therefore was compatible with EC law 96 . It is this judgment that was appealed by Vodafone and was ruled upon by Evans‐Lombe J in the High Court. 8.2. The ruling In the Vodafone 2 case, Evans‐Lombe J’s essentially answered the question put to the national court by the ECJ’s judgment in Cadbury Schweppes, and in so doing gives his interpretation of the compatibility of the UK CFC rules with EC law. Evans‐Lombe J first considered to what extent the rulings of the ECJ are binding on the UK Courts in the context of s2 of the European Communities Act 1972 97 . He concluded that, following the principle of “conforming interpretation”, the duty of the UK Courts can be summarised as: “where legislation can be reasonably construed as to conform with the United Kingdom’s Community obligations, the English Courts must do so, even if this involves a departure from the strict and literal interpretation of the words in the legislation.” 98 In spite of this apparent requirement to interpret the UK legislation as conforming with judgments handed down by the ECJ, Evans‐Lombe J ruled that the UK CFC rules (and in particular the motive test in s748(3) ICTA) cannot be interpreted such that the application of the CFC rules is restricted to companies which form part of a wholly artificial arrangement. He confirmed that: “the Cadbury case establishes that an intention to avoid tax does not, by itself, render a transaction involving a CFC resident in a Member State, an artificial arrangement and so abusive” 99 Stating further: “The provisions of subsection (3) are unambiguous and its purpose is plain, namely, to defeat tax avoidance by parent companies resident for tax purposes in the UK… There are no words in subsection (3) which, using conventional rules of construction, are capable of being 95 See para 18 of Vodafone 2 Vodafone 2 97 See para 40 of Vodafone 2 98 See para 42 of Vodafone 2 99 See para 73(v) of Vodafone 2 96 See paras 22‐24 of construed as limiting the operation of the subsection so as to comply with Article 43 as explained in the Cadbury case.” 100 Evan‐Lombe J did not see it as the role of the judiciary to add further conditions to the application of the legislation so as to remedy what would otherwise be a statutory provision which did not comply with EC law 101 ; rather its role is to interpret the legislation as drafted. Furthermore, although not directly related to the Vodafone 2 case, Evans‐Lombe J took the opportunity to comment on the newly added s751A ICTA, expressing “doubt” as to whether or not the legislation is compatible with EC law 102 . Evans‐Lombe J ended his judgment by highlighting that “all UK taxpayers, including Vodafone, are entitled to be told by legislation, of which the meaning is plain, what the tax consequences for them will be if they decide to incorporate a CFC in a Member State” 103 . Since, in his view, the legislation is no longer clear when viewed against the background of article 43 of the EC Treaty, it must be disapplied pending the introduction of amending legislation or executive action. Thus, it is the view of Evans‐Lombe J that the enquiry raised by HMRC against Vodafone 2 should be closed, since there is no basis in law for the application of a CFC charge 104 . 9. The future of UK CFC In the absence of any other alternative, one would assume that the combined impact of Cadbury Schweppes and Vodafone 2 would have been a fatal blow to the UK CFC legislation in its current form. Indeed, the limited changes as introduced by s751A ICTA seem to be designed to be transitory, and acknowledge the fact that UK CFC as we know it is to be consigned to the history books. As Vodafone 2 was heading through the Special Commissioners hearing, on its way to the High Court, HMRC had already published a discussion document outlining its proposals for the next generation of CFC legislation 105 . The document acknowledges the changing nature of the business and technological changes since the introduction of the first CFC rules in 1984 and that the current “all or nothing” approach leaves potential risks to taxation for some companies 106 . 100 See para 73(ii) of Vodafone 2 Vodafone 2 102 See para 73(vii) of Vodafone 2 103 See para 89 of Vodafone 2 104 See para 90 of Vodafone 2 105 HM Treasury & HMRC: Taxation of companies’ foreign profits: discussion document, as referenced at: http://www.hm‐treasury.gov.uk/d/consult_foreign_profits020707.pdf (last visited 7 March 2009) 106 See para 4.3 in ibid., p.17 101 See para 73(iii) of The UK government defends its implementation of amendments to the CFC legislation after the Cadbury Schweppes judgment, suggesting that subsequent rulings by the ECJ (e.g. on thin capitalisation 107 ) have vindicated its viewpoint. However, the UK government did appear to concede that any reform of the CFC legislation would need to be drafted in such a way as to apply to both UK and foreign controlled companies in order to avoid future issues of compatibility with EC law 108 . The proposed Controlled Companies regime is designed to target “mobile” income and moves away from an entity‐focused approach towards an income‐ focused application of the rules. The proposal seeks to target passive income such as dividends, interest and royalties, but also includes any active income which would otherwise ordinarily be classified as passive income 109 . This is in line with the approach currently adopted by the German CFC legislation; rules which the German Finance Ministry sought to clarify as falling within the scope of EC law immediately after the ruling in Cadbury Schweppes was handed down by the ECJ 110 . However, perhaps most tellingly, one of the sources of passive income which would be excluded from the proposed regime is group treasury activities; in the eyes of this author, a tacit admission by HMRC that the current CFC legislation was wrong to go after Cadbury Schweppes for implementing its group treasury function outside the UK, regardless of its underlying motive for doing so. 10. Conclusions The UK CFC rules celebrated their 25 th birthday in 2009; the wonder is how they managed to last for so long without any meaningful challenge to their legitimacy. Taking his lead from Lord Nolan, Evans‐Lombe J in Vodafone 2 stated: “in enacting the CFC legislation in 1984, Parliament simply and understandably failed to anticipate the effects upon it of the [European Communities] Act of 1972” 111 . Ignorance of the law cannot be an excuse for not abiding by it – even in the case of parliamentary draughtsmen. You can be sure that HMRC would not accept this as a meaningful defence when it issues an enquiry notice to a UK taxpayer. Cadbury Schweppes sent a shockwave through the CFC legislation in the UK which, hitherto, had survived largely unscathed. Instead of accepting that a See Test Claimants in the Thin Cap Group Litigation v Commissioners of Inland Revenue, C‐ 524/04 [2007] ECR I‑2107, in which the ECJ ruled that the UK’s thin cap rules did constitute a restriction on the freedom of establishment, but that this restriction was justified as an appropriate means of preventing the artificial transfer of profits. 108 HM Treasury & HMRC, op cit., p.19 109 See paras 4.20 & 4.21 in HM Treasury & HMRC, op cit., pp.20‐21 110 Whitehead, Simon: Practical implications arising from the European Court’s recent decisions concerning CFC legislation and dividend taxation. EC Tax Review 2007‐04, p.181 111 See para 73(iv) of Vodafone 2 107 mistake had been made in the original drafting of the legislation and amending it to reflect the obligations of being a member state of the EU (something which could have been forgiven), the UK government stood between its CFC legislation and the ECJ like an over‐protective parent and refused to admit that it had done anything wrong, opting instead to tinker around the edges in the vain hope that this would deflect attention from the deep rooted problems. This defence was short lived. When Evans‐Lombe J delivered his damning verdict in Vodafone 2 of the manifest inadequacies of UK CFC legislation in light of the ECJ’s judgment in Cadbury Schweppes, the game was up. There is of course the option to appeal, but at least the UK government (to its credit) had seen the writing on the wall and was in the process of constructing an alternative system; one which would put UK and foreign companies on an even footing. Time will tell how successful the proposed changes will be, but one point is certain; the draughtsmen are on notice – any replacement that so much as looks like a restriction on the freedom of establishment will be joined by cases such as Cadbury Schweppes and Vodafone 2 in the UK CFC legislation’s “hall of shame”.