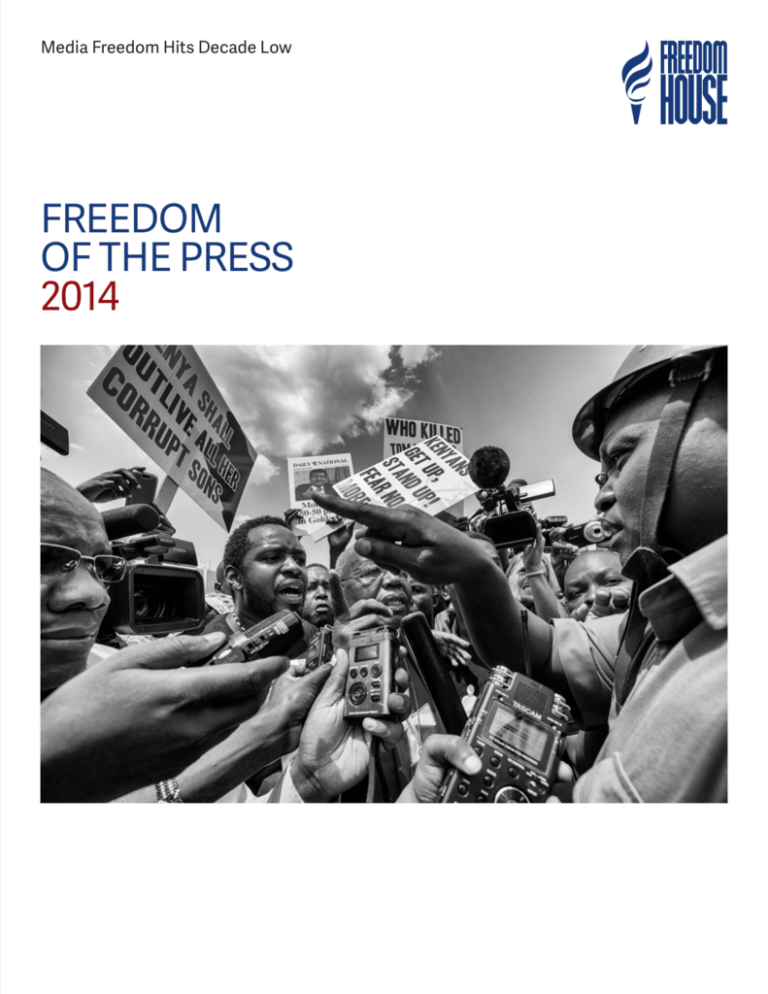

Freedom of the Press 2014

advertisement