Defining Statehood: The Montevideo Convention and its Discontents

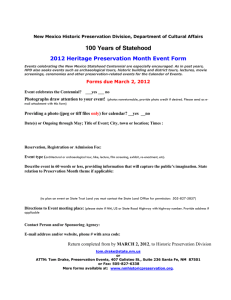

advertisement