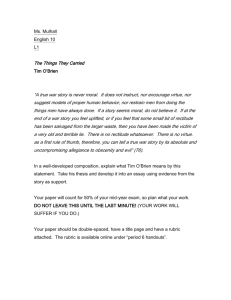

Three Languages in Tim O'Brien's The Things They Carried

advertisement