Business Law Chapter 11 Slide Number Text 1 Welcome to Chapter

advertisement

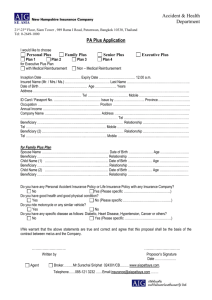

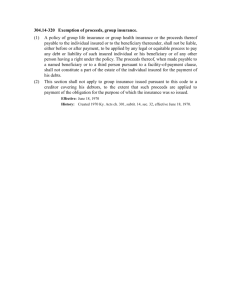

Business Law Chapter 11 Slide Number 1 Text 1 Sometimes the parties will begin contract performance only to discover that they each had a different expectation about the meaning of something in the contract. Their "meeting of the minds" was not identical. If the parties cannot resolve their differences, the court must interpret what the contract really means. As we will see, trying to determine what the parties intended is not always easy, so the legislature has established some guidelines. We will also consider issues involving a third party and the contract. So far, our contracts have been between two parties. We will look at situations where a third party was in the contract from the beginning and where the third party was added after the contract was made. For example, you contract with a well-known plastic surgeon for a "nose job." On the day of the surgery, you are in the operating room and discover a different surgeon is going to do the operation. The new surgeon says the surgery was "assigned" to her by your surgeon. Can this be done without your permission? This chapter starts with interpretation of contracts, followed by contracts involving third parties, including assignments and beneficiaries. 1 Please click on the slide to advance the presentation. 2 The parties to a contract expect that performance of the contract will be in compliance with the terms and conditions of the contract. But sometimes the terms and conditions are not perfectly clear. They are open to different interpretations by the parties to the contract. 3 If the parties cannot resolve their differences, it becomes necessary for the court to interpret what the contract means. 3 In eighteen seventy-two the legislature enacted numerous Civil Code sections to assist with interpretation of contracts. Many of the rules regarding interpretation can be learned from the selected code sections in your text. 4 The Code of Civil Procedure also contains several helpful sections for interpreting terms. You will also want to review the code sections addressed in your book. 4 After covering these sections, you will have a better idea of the legislature's approach to interpretation of contracts as of 1872. But what has happened since then? Bringing this material current, the courts in California, in searching for the intent of the parties to a contract, use an objective as opposed to a subjective standard. This analysis was discussed Welcome to Chapter 11 of the Business Law class, where we will discuss contract interpretation and the rights and responsibilities of third parties to a contract. in Chapter 7: Contracts: Concepts, Terms, and the Agreement. 4 Basically, using the objective standard, intention is found by what a "reasonable person" would determine that intention to be, considering the words and surrounding circumstances. What a party truly intends, the subjective intention, is not considered. Keep in mind that these rules of interpretation are for the purpose of determining the meaning of the words used in the contract when those words are not clear. Although Civil Code section 1642 refers to "several contracts," the courts have construed this to mean other writings, not necessarily contracts, which indicate that they are part of one transaction. 4 There are several cases in your text that address these issues. 5 Using the code sections mentioned in your text, particularly Civil Code section 1641 and Civil Code section 1642, it may be necessary to determine whether the contract is a whole (entire) contract or is a divisible (severable) contract. 5 If the contract is determined to be a "whole contract," then all of the performances within that contract are required in order to accomplish full performance. 5 The breach of any of the material provisions of the contract will allow the nonbreaching party to terminate the contract. On the other hand, a divisible contract is a contract in which separate performance obligations are given in exchange for separate performance obligations by the other party. Therefore, if one party fails to perform one of the divisible contract obligations, the victim of that breach may recover for the part breached but may not cancel the contract as the other divisible portions can be independently performed. 5 Whether the contract was whole or severable was a very important issue to the parties in Arrow Gas Company of Dell City, Texas v. Lewis, also in your text. 6 An "Incorporation by Reference" clause might appear in a contract you are reviewing prior to signing. What an "Incorporation by Reference" clause means is discussed in Republic Bank v. Marine National Bank, in your book, where the issue involved collection of attorney fees. 7 "Terms set forth in a writing intended by the parties as a final expression of their agreement ... may not be contradicted by evidence of any prior agreement or of a contemporaneous oral agreement". This is generally referred to as the 7 Parol evidence rule. 8 The purpose behind the parole evidence rule is to prevent a party to a written contract having to deal with the other party's "Yeah but" argument. 8 It is very annoying to a party in a contract to have to listen to the other party claiming "Yeah I know what the contract says—but this is really what we agreed to." 8 Parol evidence consists of any oral agreement or evidence the parties may have made prior to the written contract or at the time of entering into the written contract. 8 This evidence could consist of other writings, photographs, notes, letters, memorandums, or an oral agreement. How does the parol evidence rule work? It prevents the "Yeah but" evidence from coming into court. For the parol evidence rule to apply, there are two requirements. First, the terms of the written contract must have been the final expression of the agreement. Second, this parol evidence may not modify, alter or vary the terms of the written contract. 9 During a trial, after a writing has been admitted into evidence by one party, the second party may encounter a parol evidence objection with regard to evidence the second party is attempting to get admitted into court for consideration. The court must now determine whether the previously admitted writing was intended by the parties as a final expression of their agreement and "a complete and exclusive statement of the terms of the agreement". A court can make this determination by using one of three approaches: 9 1. "The four corner" test in which the court looks only within the four corners of the writing itself to determine whether it is the final expression of the agreement; 9 2. "The four corner-plus" test in which the court reviews not only the writing itself but other evidence as well, or 9 3. "The integration clause" test in which the court finds an integration clause in the writing that typically states, "The parties to this agreement hereby declare that this writing is the full and final expression of the bargain and includes all the terms of their agreement." 10 By using an Integration Clause, the court knows that the parties intended the writing as the final expression of their agreement, unless evidence can be introduced that the integration clause was included by fraud, duress or mistake. 10 Many standard forms, such as rental agreements, vehicle purchase contracts and franchise agreements, contain an integration clause. 10 If, by using one of these three tests, the court determines the writing is the final 0 expression of the parties' agreement, we move to the second requirement. If the court concludes the writing is not the final expression of the parties' agreement, the evidence comes into court for consideration. 10 Let’s assume the court has concluded that the writing is a final expression of the parties' agreement. The court then determines whether the parol evidence will contradict the terms of the writing. If it does, the evidence is inadmissible. If it does not, the evidence is admissible for court consideration. 10 Even though the court found the writing is the final expression of their agreement, parol evidence may still be admitted for a variety of different purposes discussed in your text. 10 EPA Real Estate Partnership v. Kang, also in your book, shows how a lack of understanding of the parol evidence rule can be very costly. 11 What we have seen so far, generally speaking, has been a contract between two parties. Sometimes a third party becomes involved. It may be that the two parties at the time of contracting intended a benefit to go to a third party. Those situations are cases involving third party beneficiaries. 12 In other situations, one of the parties to a contract transfers his or her rights in the contract or his or her duties in the contract to a third party after the contract has been formed. These are situations involving assignments of rights or delegation of duties. A simplistic way to differentiate the two would be generally: 12 If there are three parties in the contract from the beginning, it is a third party beneficiary situation; or If there are two parties in the contract from the beginning and a third party is added at a later date, it is an assignment situation. 13 A party to a contract may transfer his or her rights in the contract to another. This is called an Assignment of Rights. In the alternative, if a party to a contract transfers his or her duties in that contract to another, this is called a Delegation of Duties. A party to a contract may make an assignment of rights and a delegation of duties to different third parties or to the same third party. 14 The term "assignment" is generally used to cover both an assignment of rights and a delegation of duties. 14 Assignments may be made verbally, except when a written assignment is required if the subject matter of the contract is one which must be in writing under the statute of frauds, or a statute requires the assignment to be in writing. However, having come this far in the contracts area you would, of course, put the assignment in writing and have it signed. 14 When an assignment is made, depending on the nature of the contract the assignment may either be a "partial assignment" or a "total assignment." 14 On a contract to repay money loaned, the creditor to a contract cannot make a partial assignment of a claim against the debtor without the debtor's consent. The debtor may not like the idea that the creditor has unnecessarily increased the debtor's burden by splitting the claim up into multiple pieces assigned to different assignees. 15 Whether or not a contract is assignable will depend upon the nature of the contract and the terms and conditions contained therein. 15 As a general rule, contracts, whether bilateral or unilateral, are assignable without the permission of the other party, but there are two major exceptions. One is when a clause in the contract prohibits assignments and the other is when an assignment changes a parry's duty or risk. 15 The contract may contain a provision providing that there can be no assignment of rights or delegation of duties involving the contract, or permission must be given by the other party before such an assignment can be made. These prohibitions are generally enforceable in court. On occasion, the court has chosen to disregard or modify the contractual prohibition against assignment. For example, an assignment may be made of money due or to become due in a contract even though the contract contains a prohibition against assignments. Additionally, once a party to a contract has a valid claim for damages for breach of contract, that claim, as well as any judgment resulting from the breach, may be assigned. 15 However, an individual who has a claim against another for a personal wrong, such as a claim for money damages as a result of a tort committed by another, cannot assign that claim. Damage amounts for personal wrongs, unlike damage amounts for breach of contract, are too individualized or "personal" to be assigned to others. 15 Contracts that are personal in nature are not assignable without consent. 15 These contracts usually involve personal skill or expertise, or are based on creditworthiness. For example, you contracted with a doctor to operate on you because of the doctor's skill. The doctor cannot assign the contract to another doctor without your consent. The reason is that the performance received from another would be something different than that for which you bargained. Most residential rental agreements contain a clause prohibiting assignment because it would change the landlord's risk. Additionally, an assignment that changes a party's duty in the contract is not allowed, as it would require performance different than that to which was agreed. For example, a contract to paint a person's portrait cannot be assigned to another without the subject's permission. See La Rue v. Groezinger, in your text, for reference. 16 There being no other objection to the assignment of a contract, its assignability is, in the last analysis, a question of the intention of the parties, to be determined by construction of its terms. It is not necessary that the parties expressly provide for assignability in order that the rights arising under a contract be assignable. You will want to explore assignments further utilizing the example outlined in your text, which looks at 16 Rights of the Assignee Against the Assignor, Competing Assignees, and Delegation of Duties 17 In third party beneficiary contracts, there are three parties mentioned in or intended to be in the contract at the time of contracting 18 Over time, necessity has caused California to classify beneficiaries into two groups: incidental beneficiaries and intended beneficiaries. 19 An Incidental Beneficiary is a third party who will benefit from the contract between the parties, but that benefit is so removed and remote that the beneficiary receives only an incidental benefit from the contract. The parties to the contract did not make the contract "expressly for the benefit" of an incidental beneficiary. 19 The incidental beneficiary has no rights in the contract and cannot sue to enforce it. 19 For example, a contract to build a football stadium would benefit an adjoining property owner who would use the property for a "bar and grill," but the property owner cannot sue to enforce the stadium contract if one of the parties backs out. 20 An Intended Beneficiary is a party that is intended to receive a benefit in the contract. The contract was made "expressly for the benefit" of this party. 20 A contract made expressly for the benefit of a third person may be enforced by him at any time before the parties thereto rescind". 20 The benefit is either payment of an obligation that is owed to the beneficiary or a gift. Typically, the third party beneficiary is identified in the contract from the beginning. For example, the classic third party beneficiary contract is life insurance. There are three parties in the contract from the beginning: the insurance company, the person paying the premium whose life is insured and the person designated as the recipient of the proceeds when the insured dies. In this case, the beneficiary is an intended beneficiary, a "donee beneficiary," as the benefit is a gift. 20 On the other hand, the intended beneficiary of a life insurance contract could be a creditor of the insured, a "creditor beneficiary." In this case, the insured owes money to the creditor and the debt will be paid from the insurance proceeds when the insured dies. The third party beneficiary is not a true party to the contract in the sense of having a performance obligation, but derives a benefit from the contract. In the example of the life insurance contract, the insured is the promisee, and the insurer is the promisor. The promisor's duty under the contract is not going to be performed to the promisee, rather it is to be performed to the beneficiary. Since the promisor owes a duty to the intended beneficiary, if that duty is not performed it may be enforced by the promisee suing the promisor to specifically perform the contract. The intended beneficiary can enforce the promise by either suing the promisor for the benefit as a third party beneficiary to the contract, or suing the promisee for the debt that is owed if the intended beneficiary is a "creditor" beneficiary. 20 In re the Marriage of Smith & Maescher, in your text, involves the problem of who can sue and for what they can sue. 20 The promisor can assert any defense or setoff against the intended beneficiary if the defense or setoff is good against the promisee. Therefore, if the promisee breaches the contract with the promisor and the promisor's damages are in excess of the amount the promisor was obligated to pay under the contract, the intended beneficiary will not be entitled to recover anything from the promisor. Once again, if the intended beneficiary has a prior valid claim against the promisee, the intended beneficiary can sue on that prior obligation. 20 Since the third party beneficiary is typically in the contract from the time of formation, can the promisee or the promisor individually or jointly change the contract so that it will limit or eliminate the benefit to be received by the third party? The answer is yes, if the promisor and promisee have a provision in the contract allowing a change that will affect the intended beneficiary. The answer is no, if there is a provision in the contract restricting or eliminating the ability of the promisor and promisee to affect the intended beneficiary. However, in the absence of any provision in the contract limiting the power of the promisor and promisee to effect the intended beneficiary, the promisor and promisee have the power to change or eliminate the benefit to the third party, unless the beneficiary has changed his or her position in reliance on the benefit to be received. See Schauer v. Mandarin Gems of California, also in your text. 21 This concludes the lecture for this chapter on Interpretation and Third Parties. We covered Interpretation and Legislation, Parol Evidence, Contracts and Third Parties, Assignment, and Third Party Beneficiary Contracts.