the panas-x - University of Iowa

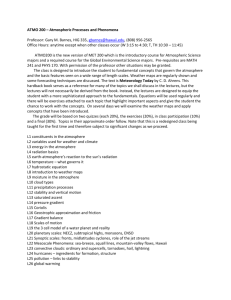

advertisement