study aid

advertisement

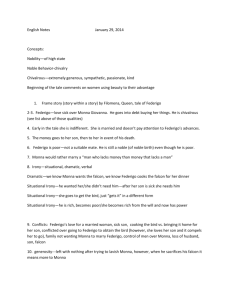

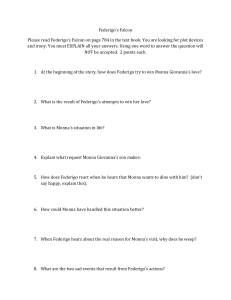

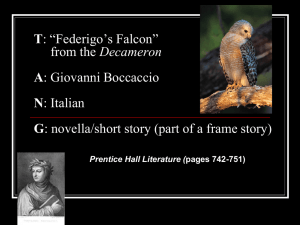

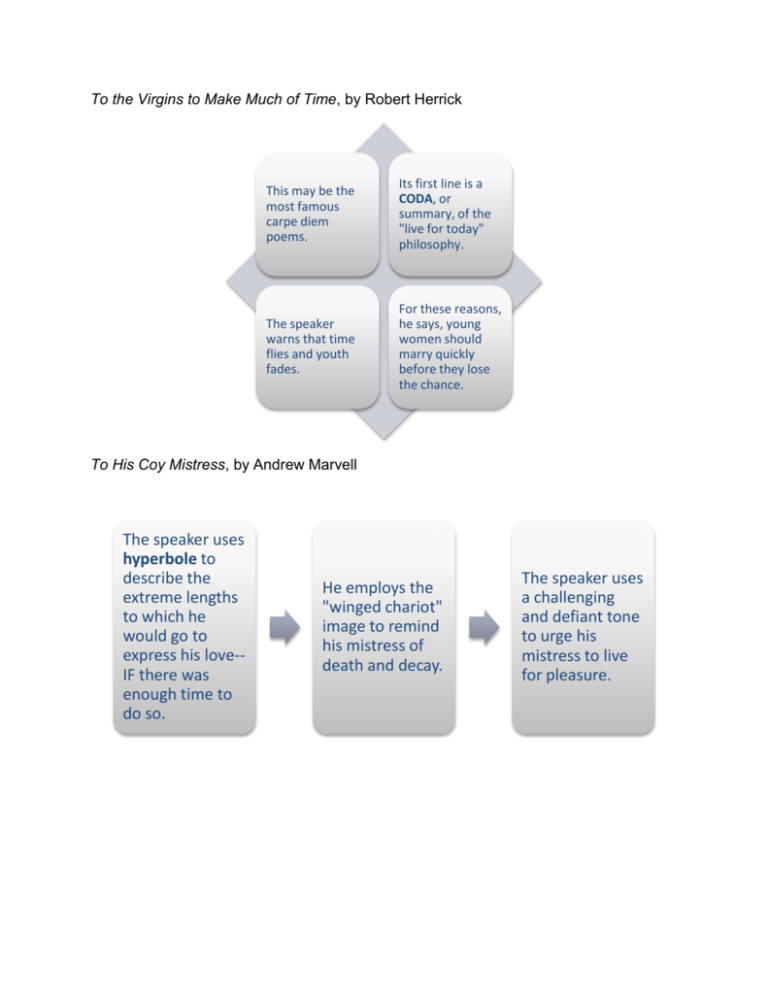

To the Virgins to Make Much of Time, by Robert Herrick This may be the most famous carpe diem poems. Its first line is a CODA, or summary, of the "live for today" philosophy. The speaker warns that time flies and youth fades. For these reasons, he says, young women should marry quickly before they lose the chance. To His Coy Mistress, by Andrew Marvell The speaker uses hyperbole to describe the extreme lengths to which he would go to express his love-IF there was enough time to do so. He employs the "winged chariot" image to remind his mistress of death and decay. The speaker uses a challenging and defiant tone to urge his mistress to live for pleasure. Porphyria’s Lover, by Robert Browning This dramatic monologue opens with a description of the setting (according to the speaker): a violently windy/rainy night. The speaker waits for Porphyria; then describes her entrance and her loving embrace. He strangles her to make her his forever, imagining she welcomes this as a release from unwanted bonds. The speaker notices God has not reacted to the deed. Still, he complains that although she worships him, she is too weak to commit herself to him totally. The Passionate Shepherd to His Love, by Christopher Marlowe In this pastoral, the Shepherd urges his love to "Come live with me and." He describes some of the pleasures of the countryside that he and his love will enjoy, and he lists things he will make for her, including a cap of flowers and slippers with golden buckles. He promises shepherds will dance and sing for her delight each morning. The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd, by Sir Walter Raleigh The clever nymph says not every shepherd is honest. She resonds to the pleasures and gifts that were offered by speaking of reality. She ends by saying she might be persuaded IF youth and love lasted forever. For example, she says rivers rage; they are not always calm. Flowers fade; they are not always beautiful. Ozymandias, by Percy Bysshe Shelley This sonnet is a haunting reflection of the transience of earthly power. The first speaker quotes a desert traveler who came upon the ruins of a monument to Ozymandias, a pharaoh in ancient Egypt. The traveler, in turn, quotes the ruler's boastful inscription on the monument's pedestal. Amid the ruins, the inscription becomes an ironic comment on the vanity of human ambition. The only powerful thing that remains is the expression the scuptor captured on the statue's face, but even that the sand and wind are in the process of destroying. The last line suggests the irony of the situation: "The lone and level sands" will eventually erase the artist's, as well as the pharaoh's, bid for immortality. Ah, Are You Digging on My Grave, by Thomas Hardy The speaker, a dead woman, asks if the digger on her grave is her lover, but she is told he has just married another. She asks if her kin are digging, but she is told they see no point in tending her grave. She asks if it's her enemy who digs, but she is told her enemy no longer thinks about her. She finally learns the digger is her dog, merely buring a bone. Holy Sonnet 10, by John Donne The speaker taunts Death, asserting Death itself will die-because death is the soul's deliverance into eternal life. Death is also described as a slave of "fate, chance, kings, and desperate men." Therefore, Death can inflict only a temporary "sleep"; the soul will awaken, live eternally, and defeat Death. Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night, by Dylan Thomas The speaker urges his father not to submit quietly to death, contending that people near death should struggle against it. He asserts those with true wisdom, even though they know death is inevitable, rage against dying. He looks for a sign that his father, at the end of his life, will challenge death, whether through cursing, blessing, or crying. Federigo’s Falcon, by Giovanni Boccaccio The nobelman Federigo is so in love with Monna Giovana, a virtuous married woman, that he impoverishes himself trying to win her and is forced to move to a small farm w/ one one "valuable" possession, a falcon. After Monna Giovanna's husband dies, she and her son move near Federigo, where the boy grows fond of the falcon. When the boy becomes ill, he asks his mother for the falcon. Monna Giovanna reluctantly goes to Federigo and offers to dine with him. Honored, Federigo kills the falcon to serve as a meal worthy of her. The mood is elevated later when Monna Giovanna marries Federigo, whose noble gesture has won her heart. Monna Giovanna makes the request. Federigo, devastated, explains the situation. The sad irony of the event is intensified when Monna Giovanna's son dies.