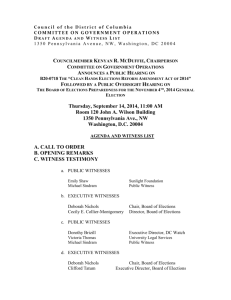

Evaluation of young witness support: examining the impact on

advertisement