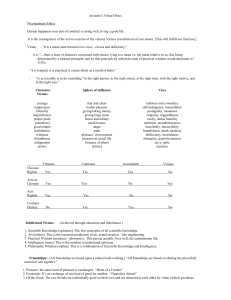

the twelve virtues of a good teacher

advertisement