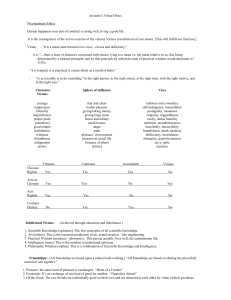

the epistemology of linda zagzebski pamplona 2004

advertisement