Between 'what we know and what we do not yet know'

advertisement

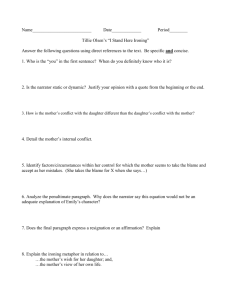

Between ‘what we know and what we do not yet know’1 Alice Munro’s ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’ Aloka Patel Narratives of growing-up or coming-of-age of a person from childhood and ignorance to the attaining of some vital knowledge about the world and the self, which have traditionally been referred to as bildungsromane, have particularly appealed to and inspired women writers of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Especially for women writers of minority and ethnic groups from former European colonies, the bildungsroman has transformed into a discursive tool to deconstruct imperialism and resist discriminations of race, class and sex, and to articulate multiple problems relating to the understanding of their identity. Carol Lazzaro Weis, in pointing out the difference between classical bildungsroman and its more modern form, also dwells upon the various ways in which postcolonial women writers find it relevant for their purpose: Nostalgic bereavement of loss, always a part of the definition of the form, takes a new relevancy in the more recent manifestation of the genre. Nostalgia, loss, home and community, and the generation gap, spoken predominantly in terms of the mother-daughter relationship rather than the father-daughter conflict of the 1970s, are all themes which characterize the more recent exploitations of the Bildungsroman tradition by women writers.2 The trope of coming-of-age in female stories invests in them possibilities of opposition to the traditional bildungsroman. Such stories make a conscious effort to show that female development involves repression of personal desires for which society, social norms and patriarchal ideologies are held responsible. The identity that emerges as a result is defined in terms of gender and race, and the woman protagonist victim is seen to be shuttling between her desire for a pre-oedipal state and coming to terms with her present ambivalent identity. Typical of such examples are Merle Hodge’s Crick Crack, Monkey (1970), Jamaica Kincaid’s Annie John (1985), Paule Marshall’s Brown Girl, Brownstones (1959), and Patricia Grace’s Dogside Story (2001) to name only a few. Such fictions by women seem to claim that women’s experience of life and reality are different from that of men. Indeed they are different, in as much as women and men differ genetically, physically and emotionally. However, even as experiences of the girl child are different from those of boys, literary representation of certain events as catalytic in the development of a child growing up in a particular culture, community, and family, are in my opinion, to certain extent similar irrespective of the gender of the writer or the protagonist. In this regard this paper will focus on Alice Munro’s short story ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’ (1968) as a narrative of the growing up of a female protagonist, not into a gendered being, but a more mature individual in relationship with her immediate family and society. Simultaneously, this essay will discuss the psychological development of the narrator’s father as perceived by his daughter, through memory and narrative, with emphasis on human relationships as primarily 1 Carolyn Kay Steedman, Landscape for a Good Woman: A Story of Two Lives (New Jersey: Rutgers UP, 1987) 141. 2 Carol Lazzaro Weis, ‘The Female Bildungsroman: Calling it into Question,’ NWSA Journal 2.1 (1990) 24. Between ‘what we know and what we do not yet know’: Alice Munro’s ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’. Aloka Patel. Transnational Literature Vol. 6 no. 2, May 2014. http://fhrc.flinders.edu.au/transnational/home.html determining an individual’s identity. Although it is the story of initiation of a young girl, and about a single incident in her life that introduces her to the adult world, her story fits into the genre of the bildungsroman, a term which according to Susan Cocalis has been traditionally defined as a ‘process by which a young [fe]male hero discovers [her]self and [her] social role through the experience of love, friendship, and the hard realities of life.’3 Considering its chief concern with the development of its protagonist, I have deliberately changed the gender terms to address the female protagonist under consideration, since, as Cocalis goes on to state, ‘the Bildungsroman is traditionally defined in terms of content rather than form and since there is no consensus on what constitutes the genre’ (399). This paper looks therefore at how Munro represents a defining moment in the life of a child and her father, and brings out, in a poignantly unexpected way, the hidden dimensions of her characters, through the narrative lens of a fairly young narrator, ‘nothing less than the child entering into the ardours and the responsibilities of her inheritance, the transmission from father to daughter of human tradition and attitude to life.’4 As the story advances we begin to understand that sex is only one among many other factors, such as complexity of human relationships, geographical location, economic status and religious faith of the individual, which determine a self-identity. The young female protagonist is seen as an ordinary human being in whom the reader identifies as sharing her or his personal experiences of everyday events, such as going out for a walk with one’s father, which when recollected in moments of calm reflection go on to take significant proportions. Not a lifelong negotiation of incompatible identities but little embarrassing moments such as going to market with her mother dressed outrageously in inappropriate clothes, or meeting her father’s girlfriend; little surprises that life springs, and uneasy secrets that need to be prudently guarded, are what leave lasting impressions on the consciousness of both the protagonists, marking these different selves vis-à-vis the social space they occupy. The story reconfigures certain moments of the female protagonist’s childhood unsettling the reader’s presumption of predictable consequences as is found in more recent representation of such events. The young girls like Annie in Kincaid’s Annie John, Selina Boyce in Paule Marshall’s Brown Girl, Brownstones, or Saru in Shashi Deshpande’s The Dark Holds No Terrors would predictably grow up to be rebels against an oppressive patriarchal society serving as mouthpiece for their authors’ views on postcolonial cultural inheritance. However, ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’ does not fit in with the confirmatory agenda of some contemporary theories or narrative modes. Although critics like Coral Ann Howells have taken help from theories of feminist philosophers like Luce Irigary in order to understand the Munro story, such readings give only partial understanding of the female characters. Munro’s comments on her style of writing can be illustrative of her refusal to conform to such theories: ‘I’m not an intellectual writer. I’m very, very excited by what you might call the surface of life … It’s just a feeling about the intensity of what is there.’5 The story, in fact, is a reinscription of everyday incidents narrated with consummate skill. Set in Canada of the 1930s ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’ is about a girl and her father coming to terms with the world and its perceived difficulties in times of the Great Depression. Although the age of the girl is not mentioned the narrative suggests a precocious and perceptive 3 Susan L. Cocalis, ‘Transformation of Bildung from an Image to an Ideal,’ Monatshefte 70. 4 (1978) 399. Walter Rintoul Martin, Alice Munro: Paradox and Parallel (Alberta: U of Alberta P, 1987) 3. 5 Alice Munro, Interview. Eleven Canadian Novelists by Graeme Gibson (Toronto: Anansi, 1973) 241. 4 2 Between ‘what we know and what we do not yet know’: Alice Munro’s ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’. Aloka Patel. Transnational Literature Vol. 6 no. 2, May 2014. http://fhrc.flinders.edu.au/transnational/home.html young girl in her pre-adolescent days growing out of childhood to knowledge and experience. The father, on the other hand, in the beginning has a childlike approach towards serious emotional and financial problems hoping to ward off difficulties by trivialising them. The girl protagonist narrates the story in first person; however, her keen analytical power and the mature tone of her recollections of the era may be ascribed to the intellectual faculties of an older woman. This doubling of perception reconstructs not only the father’s identity but also focuses with hindsight on the malleable persona of her own younger self, highlighting the ‘getting of wisdom’ or ‘initiation’ as the central trope of the writing. Revealing her complex emotional relationship with her parents, which impinges upon the psychological development of the girl, the narrator begins by pointing out the difference between her father and mother. While the father speaks the language of the child: ‘Want to go down and see if the Lake’s still there?’, and instinctively relates to her, the mother in opposition to her husband, is concerned more about her child’s education. The narrator’s inclination towards her father could therefore be a result of her presumption of a shared ignorance and denial of the hardships of life. The possible outing with her father is juxtaposed against the narrator’s distancing from her mother: ‘We leave my mother sewing under the dining-room light making clothes for me against the opening of school’ (3). These first lines also draw out a difference between two forms of knowledge: one, gained through empirical experience, and the other more oppressive academic form of knowledge whose source lies in books and schools – the two forms represented respectively by the father and mother. One of these the narrator will accept and the other reject. The mother, with her ‘old suit and old plaid wool dress’ which she has ripped up, making her daughter ‘turn for endless fittings,’ is, so to say, tied to deep-rooted customs and tradition, becoming a symbolic personification of ideologies that she imposes on the girl making her feel uncomfortable: ‘sweaty, itching from the hot wool, ungrateful’ (3). The beginning, therefore, anticipates things to follow – a more intimate sharing of knowledge between father and daughter and a rejection of traditional knowledge through formal education. True to the vein of Munro’s story-telling strategy which makes no use of traditional ‘intellectual’ methodologies, unquestioning conformity to any kind of formal education, for the narrator, undoubtedly entails ‘endless fittings’ (3) by regulating one’s life/writing to suit the social/intellectual order and adopting its ‘moral’ values which, in most cases, are out of sync with individual needs. While the mother keeps the children close at home, the father opens the girl’s eyes to the world outside the front yard and to the need for compassion towards those less fortunate. Her escape for the evening is her visit to Lake Huron with her father. At the edge of the water, above the beach, her father rolls a smoke and speaks to her of the awesome powers of nature that shaped the landscape long ago: All where Lake Huron is now, he says, used to be flat land, a wide flat plain. Then came the ice, creeping down from the North, pushing deep into the low places ... And then the ice went back, shrank back towards the North Pole where it came from, and left its fingers of ice in the deep places it had gouged, and the ice turned to lakes and there they were today. (4) Indeed, as Walter Rintoul Martin notes, the daughter here ‘is being initiated, naturally enough … into an awareness of history and the human condition, especially its precariousness and possible terror’ (2) by claiming that ‘his affection tempers the fright for his lamb … the father makes the 3 Between ‘what we know and what we do not yet know’: Alice Munro’s ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’. Aloka Patel. Transnational Literature Vol. 6 no. 2, May 2014. http://fhrc.flinders.edu.au/transnational/home.html drama not altogether horrifying, but meaningful, manageable and stimulating for the daughter.’6 However, Martin overlooks the fact that the daughter is not suitably impressed by her father’s narration and doubts his ability to recount historical or geographical events. Questioning historical memory and any form of knowledge that is gained second-hand, and emphasising the experience of the here and now, the narrator observes: I try to see that plain before me, dinosaurs walking on it, but I am not able even to imagine the shore of the Lake when the Indians were there, before Tuppertown. The tiny share we have of time appals me, though my father seems to regard it with tranquillity. Even my father, who sometimes seems to me to have been at home in the world as long as it has lasted, has really lived on this earth only a little longer than I have, in terms of all the time there has been to live in. He has not known a time, any more than I … He was not alive when this century started. I will be barely alive – old, old – when it ends. I do not like to think of it. I wish the Lake to be always just a lake, with the safe-swimming floats marking it, and the breakwater and the lights of Tuppertown. (4-5) The narrator suggests that her father cannot comprehend the immensity of time. In biological terms he is not much older than she is and ‘has not known a time, any more than [her].’ After all the life-spans of men and women are hardly a century, and a superficial knowledge of history along with the unreliable nature of memory gives only a partial vision of truth. Philosophers like Michel Foucault have explicated on the fallibility of any kind of knowledge and the impossibility of arriving at fixed and stable answers: And the great problem presented by such historical analyses is not how continuities are established, how a single pattern is formed and preserved, how for so many different, successive minds there is a single horizon, what mode of action and what substructure is implied by the interplay of transmissions, resumptions, disappearances, and repetitions, how the origin may extend its sway well beyond itself to that conclusion that is never given – the problem is no longer one of tradition, of tracing a line, but one of division, of limits ... In short, the history of thought, of knowledge, of philosophy, of literature seems to be seeking, and discovering, more and more discontinuities, whereas history itself appears to be abandoning the irruption of events in favour of stable structures.7 Ajay Heble also points out that by beginning her story with a ‘peculiar lack of assertion’ – ‘Want to go down and see if the Lake’s still there?’ – Munro ‘is already questioning the assumption that reality is stable and fixed – that it is something we can ever fully know.’8 Since there is no resolution to the complexities of time, nor are there easy solutions to problems that life poses, and although her father claims to possess the panacea to all ills: ‘And have all liniments and oils,/ For everything from corns to boils …’ (5), the narrator doubts the legitimacy of such easy answers. The mother, on the other hand, ironically takes solace in memories of happier times when they lived in the silver-fox farm at Dungannon which, like many farms of the time had suffered the blow of the Great Depression: ‘My mother tries … to imitate the conversations we used to have at Dungannon, going back to our earliest, most leisurely days … “Do you remember when 6 Martin, 3 Michel Foucault, Archaeology of Knowledge (New York: Routledge, 2002) 5-6. 8 Ajay Heble, The Tumble of Reason: Alice Munro’s Discourse of Absence (London: U of Toronto Press, 1994) 20. 7 4 Between ‘what we know and what we do not yet know’: Alice Munro’s ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’. Aloka Patel. Transnational Literature Vol. 6 no. 2, May 2014. http://fhrc.flinders.edu.au/transnational/home.html we put you in your sled and Major pulled you?”… “Do you remember your sandbox outside the kitchen window?”’ (6). She even pretends to be a lady and wishes to mould her daughter in her image, which the daughter resists. Neil Sutherland in his article ‘When You Listen to the Winds of Childhood, How Much Can You Believe’ refers to a passage in the story which registers the narrator’s acute sense of embarrassment triggered by the idiosyncratic behaviour of her mother who tries to make her daughter conform to the mores of a bygone time: She wears a good dress … a summer hat of white straw, … and white shoes … I have my hair freshly done in long damp curls which the dry air will fortunately soon loosen, a stiff large hair ribbon on top of my head … We have not walked past two houses before I feel we have become objects of universal ridicule … She walks serenely like a lady shopping, like a lady shopping, past the housewives in loose beltless dresses torn under the arms. With me her creation, wretched curls and flaunting hair bow, scrubbed knees and white socks – all I do not want to be. I loathe even my name when she says it in public, in a voice so high, proud, and ringing, deliberately different from the voice of any other mother on the street. (6) Ildikó de Papp Carrington describes the girl’s overdressing as ‘the child’s costumed public identity.’9 Her shame is revealed by her refusal to identify publically with her name enunciated the way her mother says it in a pathetic attempt to make the family stand out as being better than the common townspeople. In fact, the narrator never reveals her name in the course of the storytelling, denying a traditional identity marker. One’s identity like one’s name appears to be something personal and intimate, not to be put on public display. She would suggest that there is nothing unique about her experiences; that she is like any ordinary girl growing up in a particular social setup. Whether it be the father’s discreet dramatisation of a geographical past or the mother’s desperate attempts to ‘fix’ or place the daughter in a glorious familial past, the daughter rejects both. What she sees, especially in her mother’s desperate attempts to recover the past and pretensions to being a ‘lady’, is a pathetic enactment of the impossibility of reconstructing the past through an act of narration, which nevertheless she herself is also engaged in. Resisting the oppressive presence of the past even while she finds it impossible to disengage herself from the act of narration, the narrator points to the unreliability of any kind of narration since memory would always already be selective: ‘I pretend to remember far less than I do, wary of being trapped into sympathy or any unwanted emotion’ (6). In fact the entire narration involves an overlapping of past over the present and is an expression of how the past impinges upon the present. What knowledge of the past the narrator chooses to accept will have a greater import on the development of her personality. Similarly, a conscious acceptance of the present will be the crucial defining moment of her father’s life. Foucault reflects on the moment of self-awakening: The question of how the knowledge of things and the return to the self are linked … appears around that very old, ancient theme which Socrates had already evoked in the Phaedrus when, as you know he said: Should we choose the knowledge of trees than the knowledge of men? And he chose the knowledge of men … [W]hat is interesting, important, and decisive is not knowing the world’s secrets, but knowing man himself … Demetrius distinguishes between what is and what is not worth knowing … with 9 Ildikó de Papp Carrington, Controlling the Uncontrollable (Illinois: Northern Illinois UP, 1989) 23. 5 Between ‘what we know and what we do not yet know’: Alice Munro’s ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’. Aloka Patel. Transnational Literature Vol. 6 no. 2, May 2014. http://fhrc.flinders.edu.au/transnational/home.html knowledge of the world, of the things of the world on the side of useless knowledge, and knowledge of man and human existence on the side of useful knowledge.10 Both, the narrator and her father reject the ‘knowledge of trees’ and accept ‘knowledge of man and human existence’ as useful knowledge. The story is neatly divided into two parts to demonstrate the point. The first part gives us a view of traditional knowledge that is handed down but fails to leave any impression on the narrator’s mind. Although geographical upheavals ‘had gouged’ and ‘left fingers of ice’ on the landscape, such knowledge is of no use to her. The second part of the story is a narrative of events that lead her father to a stoic acceptance of reality, at the same time initiating the narrator into workings of the adult world. The first part of the story develops the setting by describing the father’s failure in business and the mother’s psychological depression. It also gives us a glimpse of the narrator’s relationship with both of them. While the father shares lighter moments of his evening with her the mother is engaged more in her household chores and initiates the daughter into lady-like etiquettes and feminine behaviour which to the girl appear uncalled for and artificial. In the spirit of the traditional bildungsroman where the path to self-awareness involves a journey that the protagonist undertakes, in the second half of ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’ the narrator with her father goes out on a symbolic journey towards knowledge and a mature understanding of the realities of life. The girl is given a glimpse of the professional hazards that her father faces in his work and also something is revealed of his past personal life when she is taken with her brother on a field trip. Her father has been forced by circumstances to accept a job as a travelling salesman. The narrator reports on the bluff romantic air he enacts in relation to the job which he perhaps never enjoyed. The outing turns out to be a revelation of her father’s vulnerability opening a new dimension of his life which the girl hitherto had not perceived. She is forced to reassess their lives, involuntarily pushed towards greater self-awareness. The fieldtrip stands as a metaphorical marker for a point in time when the girl confronts the real world beyond the security of the family circle. Patricia Reis discusses the role of father in the development of a daughter’s personality: Despite the changes occurring in gender roles, fathers are still experienced by daughters as a symbolic link to the outside world. It is well understood, both objectively and subjectively, that a daughter’s relationship to her father can make or break her feelings of self-esteem and self-confidence, her understanding of herself as a woman, her belief in herself and her own authority as she enters into the world.11 Unlike the little walks with her father after supper where she witnessed the utter poverty of farmers and the degenerating downtown industrial areas, in this trip she symbolically passes through her father’s ‘territory’ of deserted farmyards and gloomy lanes to have a glimpse of his personal love-life before his marriage. Unlike her brother who is ‘too young to spell’ (9) and ‘does not notice enough’ (15) the protagonist is at an age when she is beginning to ‘notice’ her father’s desperate attempts at a decent living, and also his heroic but ironic romanticisation of present misfortunes. Wondering about his duties as a salesman and his dealings with mysterious 10 Michel Foucault, The Hermeneutics of the Subject: Lectures at the College De France 1981 1982 (New York: Palgrave, 2001) 230-32. 11 Patricia Reis, Daughters of Saturn: From Father’s Daughter to Creative Woman (New York: Continuum, 1997) 22. 6 Between ‘what we know and what we do not yet know’: Alice Munro’s ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’. Aloka Patel. Transnational Literature Vol. 6 no. 2, May 2014. http://fhrc.flinders.edu.au/transnational/home.html clients the narrator is undoubtedly in awe of her father’s heroism in turning even his misfortunes into ‘a comic calamity’ (7). But her opinion undergoes a change when she becomes witness to her father’s humiliation in a client’s house where in response to his ‘hulloring’ the contents of a chamber pot are poured down. The father barely escapes the ‘pee’, but his sense of humiliation is quite apparent, and the daughter perceives his discomfiture. The incident reveals to her another aspect of her father’s character: she sees him as an ordinary human being with flaws and foibles of common men, and that his stoic exterior hides a frail and sensitive nature. The experience is the beginning of an awareness of others that initiates the narrator into the harsh realities of the outside world. In a move that is best described as impulsive the father steers his car towards a lane with which his children are not familiar. The narrative suggests not only an unfamiliar geographical landscape but also an unfamiliar psychological landscape in which the father discloses a hidden dimension to his personality as a lover. In what appears to be a random drive he takes his children to a house where they meet a ‘short, sturdy woman’ and her blind mother. They too are apparently victims of the Depression and are struggling to make ends meet. What strikes the young narrator most about this woman is her cheerful exterior like her father’s, and her stoic resignation to adverse circumstances. She also notices that her father communicated better with the lady than he does with his wife, who, as her father says, ‘isn’t liable to see the joke,’ and he doesn’t want the children to tell her about the ‘chamber pot’ incident for fear of her unsympathetic response. However, Nora, the father’s girl friend, ‘laughs almost as hard as [her] brother did at the time’ (13), making the burden of the humiliation much lighter to bear. With Nora, a romantic denial of reality never becomes a necessity. She is an example of a woman who accepts the hardships of life without suppressing the fleeting and short-lived joys that come her way. The narrator had earlier commented upon her mother’s hard nature, ironically remarking on her constant complaints after the failure of business in the silver-fox farm: ‘(it did not matter that we were poor before; that was a different sort of poverty), and the only way to take this, as she sees it, is with dignity, with bitterness, with no reconciliation’ (5). The mother refuses to see and take comfort from the little joys that life offers and, which to a child are a luxury: No bathroom with a claw-footed tub and a flush toilet is going to comfort her, nor water on tap and sidewalks past the house and milk in bottles, not even the movie theatres and the Venus Restaurant and Woolworths so marvellous it has live birds singing in its fan-cooled corners and fish as tiny as fingernails, as bright as moons, swimming in its green tanks. My mother does not care. (5) Nora, on the other hand, like her namesake in Ibsen’s path-breaking play A Doll’s House, has a childlike simplicity that makes the most of whatever is available. She offers her lover whisky and would not even save the last bottle, like he warns, ‘in case of sickness’ (13). She drinks to his luck and even transfers some of her warmth and joviality to the children. While she would play the gramophone for the boy, she would teach a few steps of dance to the girl. The narrator feels the warmth of the woman’s comforting presence but she is also ‘embarrassed’ by her mature and gross physicality. She is left ‘breathless’ at the speed with which her acquaintance with Nora flings her into the adult world of unrequited love and unsatisfied desires. Nora becomes a learning experience, the turning point in the narrator’s life. The whole experience has the effect of a ritual of initiation. Mordecai Marcus writes that ‘[t]he formalized behavior of so-called civilized people will appear ritualistic in fiction, chiefly under two circumstances: when it involves a response to an 7 Between ‘what we know and what we do not yet know’: Alice Munro’s ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’. Aloka Patel. Transnational Literature Vol. 6 no. 2, May 2014. http://fhrc.flinders.edu.au/transnational/home.html unusually trying situation in which a person falls back on socially formalized behaviour, or when an individual pattern of behaviour results from powerful psychological compulsion.’12 It is Nora’s psychological compulsion that transfers the young narrator to a ritualistic plane: Round and round the linoleum, me proud, intent, Nora laughing and moving with great buoyancy, wrapping me in her strange gaiety, her smell of whisky, cologne and sweat. Under the arms her dress is damp, and little drops form along her upper lip, hang in the soft black hairs at the corners of her mouth. She whirls me around in front of my father – causing me to stumble, for I am by no means so swift a pupil as she pretends – and lets me go, breathless. (14) Compared to the artificiality of her mother’s ‘lady-like’ clothes and manners which is a deliberate denial of reality, the narrator perhaps realises that Nora’s crude physicality with the ‘smell of whisky, cologne and sweat’ is more ‘natural’, stimulating yet comforting. Although at first the narrator feels strange and out of place in Nora’s company – after all, the woman is a catholic – she gradually accepts her as a warm and loving individual. Nora stands in as a mothersubstitute, prepared to initiate the young girl into knowledge of her own femininity and the world at large. The ‘embarrassing’ but intimate physical proximity during the dance with Nora also serves as a reminder to the young narrator of her own not very distant, future physical maturity. Reis notes with reference to the myth of Peresphone: Oftentimes, women, particularly women who have been father’s daughters, will feel themselves to be what [Adrienne] Rich has called ‘wildly unmothered.’ This unmothered condition sets up a longing and yearning for a special kind of touch and holding. Many women, of course, seek it in men, looking to their husbands or mates for that which only another woman can offer. This can be a source of deep and secret dissatisfaction. Men can give women many things, but they can never give the kind of touch, warmth, nurturance that connection with another woman’s body can provide. In order to love oneself fully, physical cherishing from another woman must occur as a registered knowing in our body cells. If we do not get this from our personal mother, we may seek it in dreams, find it through our daughters or sisters, or receive it from another woman. However it happens, happen it must. Until a woman knows this experience, she will never be able to feel herself united body and soul.13 She realises that like herself, her father too must feel bound by her mother’s rigid moral and social values that aimed at converting her into ‘all I do not want to be’ (6). It perhaps also dawns on the narrator that among the many losses that her father had suffered is also the loss of Nora’s love. Perhaps in a convergence of their assessment of her mother’s ideals as oppressive and ridiculous a tacit partnership begins to gradually build between the adolescent narrator and her father. The narrative seems to be building up symbolically on the ambiguity regarding who in fact of all the characters is blind. To her mother’s query of ‘Is that company?’ (10) Nora, without any reference, simply replies ‘Blind.’ All of them in fact are blind. While Nora’s aged mother is literally blind, ‘Her eyes are closed, the eyelids sunk away down’ (11), the narrator’s mother 12 Mordecai Marcus, ‘What is an Initiation Story?’ (Short Story Theories ed. Charles E. May. (Athens: Ohio UP, 1976) 190. 13 Reis 123-24 8 Between ‘what we know and what we do not yet know’: Alice Munro’s ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’. Aloka Patel. Transnational Literature Vol. 6 no. 2, May 2014. http://fhrc.flinders.edu.au/transnational/home.html chooses ‘to lie … with [her] eyes closed’ (7). The narrator too has been blind to her father’s need for love and security. Similarly, he also has been blind to Nora’s suffering by deliberately refusing to acknowledge the pain that her apparently happy exterior betrayed. Nora’s dressing up and her dance before Ben, the narrator’s father, so full of ‘buoyancy’ and whirling around before they finally bid each other goodbye, which Howells describes as her ‘flirtatiousness’14 but to me recalls the wild dance of self-sacrifice of her earlier fictional counterpart in A Doll’s House, just before she thought she was going to part from her husband for good. Performance in this case also becomes an act of resistance. All readings of A Doll’s House present Nora as the New Woman who slams the door on her husband and walks out of their marriage. However, we fail to notice the New Woman’s tragedy: her craving for love and acceptance; that if financial misfortunes had not followed, and her husband’s rigid religious biases not prevailed, Nora would have continued to live as her husband’s doll. Nora, in this case also, is a victim of her lover’s financial position and conventional religious biases. Of course, she has not walked out of the prospective marriage with Ben. It is Ben who walks out on Nora, exactly as he does at the end of this story, the narrative making a future meeting unsustainable. Nora’s grief at the parting is palpable in her quiet appeals to Ben to visit again, and the ‘unintelligible mark’ (15) she makes on the fender of the car with her touch. We cannot fail to note that the narrator has been silent about her father’s name until we meet Nora. Only after she meets Nora does her father gain an identity as an individual – other than a father, or a tolerant husband. Like the narrator we can sense the reasons for Ben and Nora’s separation, and attribute it to religious differences between Catholics and Baptists in contemporary Canada. The narrator refers to what she sees in Nora’s house: ‘There is … a picture of Mary, Jesus’ mother…. I knew that such pictures are found only in homes of Roman Catholics, and so Nora must be one’ (12). She also makes a mental note of the antipathy of her father’s family, who were obviously Baptists, against Catholics: I think of what my grandmother and Aunt Tena, over in Dungannon, used to always say to indicate that somebody was a Catholic. So-and-so digs with the wrong foot, they would say. She digs with the wrong foot. That was what they would say about Nora. (12-13) Parental opposition, therefore, must have been the cause of Ben’s separation from Nora. But it is not until we meet Nora, and know of his secret love, that we and the narrator understand Ben’s ironic denunciation of Baptists in the rhyme which he had coined: Where are the Baptists, where are the Baptists, Where are all the Baptists today? They’re down in the water, in Lake Huron water, With their sins all a-gittin’ washed away. (7) Although nothing is stated in clear terms, the narrator’s articulation of her father’s mockery of a religious order challenges orthodox values upon which a society rests. Social rules, it appears, be they religious or political, are in general apathetic to individual happiness. Such knowledge undoubtedly leads to a questioning by the subject of the factors that determine human existence and the place of the individual in the social scheme. Her understanding of her father’s life will definitely have an impact on the narrator’s understanding of her own ontological self. The narrative does not attempt to find solutions to the complexities of human identity, rather it 14 Coral Ann Howells, Alice Munro (Manchester: Manchester UP, 1988) 18. 9 Between ‘what we know and what we do not yet know’: Alice Munro’s ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’. Aloka Patel. Transnational Literature Vol. 6 no. 2, May 2014. http://fhrc.flinders.edu.au/transnational/home.html problematises the whole issue by remaining silent about the effect of the incident upon the young girl. It is up to the intelligent reader to draw conclusions from the permanence in memory of such experience. The only information given to the reader is that there is an unsaid agreement between father and daughter to keep the entire incident a secret from her mother. It is apparent that the daughter has grown up in the process. Instead of buying icecream or pop for the children the father buys a package of licorice: ‘a sweet, chewy, aromatic black substance made by the evaporation from the juice of a root and used as candy and in medicine’ (OED). It is pertinent to note that licorice is an acquired taste, a delicacy meant for grown-ups, and at times used to disguise the smell of whisky. By buying licorice for his children the father treats them as grownups. The secret tie between the father and daughter would, in Freud’s terms, be related to the ‘acquisition of femininity.’ Referring to Freud as her guide Reis writes: ‘a daughter’s relationship with her mother was the earlier and more intense attachment while the relationship with her father only assumes major significance in relation to the daughter’s later “acquisition of femininity.”’15 In the spirit of the initiation story which, in Marcus’ words, shows ‘its young protagonist experiencing a significant change of knowledge about the world or himself, or a change of character, or of both, and this change must point or lead him towards an adult world,’16 the female narrator here has had a rebirth through her experience in the company of her father. The reflective mechanics of telling the story gives the narrator not only some insight into the truth of her father’s superficial joviality, it also serves as an insight into the truth about the human condition. As the narrator reflects upon her father’s life she becomes more and more aware of the ambiguities and subtle reversals in mood and perception flowing back from our car in the last of the afternoon, darkening and turning strange, like a landscape that has an enchantment on it, making it kindly, ordinary and familiar while you are looking at it, but changing it, once your back is turned, into something you will never know, with all kinds of weathers, and distances you cannot imagine. (15) She is obviously touched by her father’s struggle to negotiate his past and present. Symbolically, as they approach home during their return to Tuppertown, the ‘sky’ too ‘becomes gently overcast’ (15). A sense of nostalgia prevails as the narrative ends with taking us back to ‘summer evenings by the Lake’ (15). Nicola King claims that memory and nostalgia are innate parts of narratives of growing up: All narrative accounts of life stories, whether they be ongoing stories which we tell ourselves and each other as part of the construction of identity, or the more shaped and literary narratives of autobiography or first-person fictions, are made possible by memory; they also reconstruct memory according to certain assumptions about the way it functions and the kind of access it gives the past. There are moments when memory seems to return us to a past unchanged by the passing of time; such memories tend to be suffused with a sense of loss, the nostalgia out of which they may be at least in part created. We long for a time when we didn’t know what was going to happen next – or, conversely, to relive the past with the foreknowledge we then lacked. But memory can only be reconstructed in 15 16 Reis 26. Marcus 192. 10 Between ‘what we know and what we do not yet know’: Alice Munro’s ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’. Aloka Patel. Transnational Literature Vol. 6 no. 2, May 2014. http://fhrc.flinders.edu.au/transnational/home.html time, and time, as Carolyn Steedman puts it, ‘catches together what we know and what we do not yet know.’17 What becomes important to the narrator, therefore, is not knowledge of her father’s secret, but a reconstruction of the past that gives her a better and more mature understanding of the man himself and through him, herself. Just as there is no possibility of revival of her father’s lost love, it is a near impossibility for the narrator to regain the innocence of her childhood days of ice cream and evening walks with her father. In his Preface to The Tumble of Reason Heble writes, ‘Munro’s texts, like her characters, repeatedly insist on the abandonment of reason.’18 However, in ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’ the protagonists, far from advocating ‘abandonment of reason’, rather are guided by prudence of action. While the father nonchalantly accepts social restrictions, the daughter matures to the realities of life. Nevertheless, the narrative hints at a continuous process of search for reconstructing the past ‘with all kinds of weathers, and distances you cannot imagine’ (15). The whole process of trying to understand oneself is but an ongoing process and every narrative act is a ‘raid on the inarticulate,’ as it were. Munro points out the unstable nature of Truth: Memory is the way we keep telling ourselves our stories – and telling other people a somewhat different version of our stories. We can hardly manage our lives without a powerful ongoing narrative. And underneath all edited, inspired, self-serving or entertaining stories there is, we suppose, some big bulging awful mysterious entity called THE TRUTH, which our fictional stories are supposed to be poking at and grabbing pieces of.19 The narrator in ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’ can, to a certain degree, be identified with the author for as Carrington notes ‘[e]ven if Munro’s protagonists do not write or create art in any way … they nevertheless adopt the psychological position of the writer, splitting into two selves, the observer and the participant.’20 In another interview, to Atlantic Unbound, Munro ponders on the compulsion of writers to narrate events of childhood: I think in my case, and in the case of many writers I’ve read, childhood events are really never lost or discarded. They may be seen in many different ways, but never lost … something about writers makes them want to recall these things, even if they are quite unpleasant, devastating things. Not in the sort of way where you get free of them or make them better, but to find out about them, to see what was really going on. This is tremendously important to me. I never think in terms of making myself a better person. I mean, recalling stories is not like what you might do with a therapist. It’s just exploring, taking out the layers of things, trying to see.21 Exploring pieces of her past as a self-examining activity, therefore, becomes important for the narrator in order to gain a better understanding of her father and herself in the past, as well as of herself in her present. Every visitation to, and narration of, the past will help her to understand her life differently from the way she has known it. The process of her growing up will, therefore, 17 Nicola King, Memory, Narrative, Identity: Remembering the Self (Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2000) 2. Heble ix 19 Jeanne Mc Culloch, and Mona Simpson, ‘Alice Munro, The Art of Fiction,’ The Paris Review 137. Web 20 Carrington 31 21 Alice Munro, ‘Interviews: “Bringing to Life”,’ Atlantic Unbound (Dec 14, 2001) Web. 18 11 Between ‘what we know and what we do not yet know’: Alice Munro’s ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’. Aloka Patel. Transnational Literature Vol. 6 no. 2, May 2014. http://fhrc.flinders.edu.au/transnational/home.html be an ‘ongoing’ one of recognition and identity reconstruction, to accommodate ‘what we know and what we do not yet know’ about the world and our possible place within it. Aloka Patel teaches in the Department of English, Sambalpur University, Odisha, India. She has worked on Jamaica Kincaid and is interested in women writers in a variety of contexts. At present she is working on representation of mythical women in Indian writings. 12 Between ‘what we know and what we do not yet know’: Alice Munro’s ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’. Aloka Patel. Transnational Literature Vol. 6 no. 2, May 2014. http://fhrc.flinders.edu.au/transnational/home.html