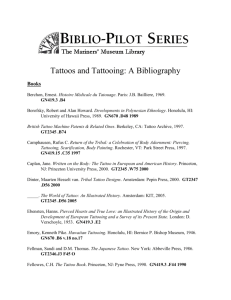

Brief - Thomas Jefferson Center

advertisement

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF VIRGINIA LASTING BEAUTY, L.L.C. and DENISE HUMPHRIES, Petitioners / Appellants, v. RECORD NO.: Chesapeake Circuit Court No.: 04-626 CITY OF CHESAPEAKE and JAMES T. DAVIS, CZA, Zoning Administrator, Respondents / Appellees. AMICUS CURIAE MEMORANDUM OF SUPPORT FOR PETITIONERS / APPELLANTS PETITION FOR APPEAL ASSIGNMENT OF ERROR1 The trial court erred in failing to determine that the City’s zoning scheme governing tattooing unconstitutionally burdens free speech and expression rights guaranteed by the United States and Virginia Constitutions. QUESTION PRESENTED Did the trial court err in failing to determine that the City’s zoning scheme governing tattooing unconstitutionally burdens free speech and expression rights guaranteed by the United States and Virginia Constitutions? (Assignment of Error A). 1 Although the Petition for Appeal lists five separate Assignments of Error, this Memorandum will only address one and the corresponding Question Presented. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ASSIGNMENT OF ERROR .....................................................................................................1 QUESTION PRESENTED ........................................................................................................1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ...........................................................................................................2 TABLE OF CITATIONS ..........................................................................................................3 STATEMENT OF THE CASE..................................................................................................4 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................................................................................4 ARGUMENT .............................................................................................................................4 CONCLUSION ..........................................................................................................................8 2 TABLE OF CITATIONS Cases Pages City of Chesapeake, et. al., v. Lasting Beauty, LLC, et. al., Chancery No. 04-626 Memorandum Opinion p. 5 (Chesapeake Cir. Ct. March 23, 2006) ................................. 4, 5, 7 Commonwealth v. Lanphear, 50 Mass. App. Ct. 1107 N.E.2d 1281 (2000) .............................6 Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Group of Boston, 515 U.S. 557 (1995) ................................................................................................................................................7, 8 Lanphear v. Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Mass. Superior Court Slip Opinion 99-1896B (October 20, 2000) .................................................................................................................6 MacNeil v. Bd. App. Boston, No. 02CV01225, 2004 WL 1895054 (Mass. Super. Aug. 8, 2004) ..........................................................................................................................................6 Minneapolis Star Tribune v. Minnesota Comm’r of Revenue, 460 U.S. 575 (1983) .................5 Satellite Broad. & Commc'n Ass'n v. FCC, 257 F.3d 337 (4th Cir. 2001) ................................7 Spence v. Washington, 418 U.S. 405 (1974)..........................................................................7, 8 State v. White, 560 S.E.2d 420 (S.C. 2002) ...........................................................................5, 6 United States v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968) ......................................................................7, 8 Other: Levins, Hoag. "The Changing Cultural Status of Tattoo Art" Tattooartist, 1998. August 2, 2006 (http:/www.tattooartist.com/history.html) ........................................................................6 Muhammad II, Lawrence, “Tattoo You,” Chicago Tribune, Nov. 4, 1997, ONLINE EDITION, pg. ZONE .................................................................................................................6 3 STATEMENT OF THE CASE Amicus adopts the Statement of Facts and the Statement of the Case and Summary of Material Proceedings Held in the Trial Court presented in the Petitioners / Appellants’ Petition for Appeal. SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT Although this case raises a number of issues worthy of this Court’s consideration, the question of whether tattooing is an art form deserving of First Amendment protection by itself justifies granting the Petition for Appeal. As the lower court recognized, ‘[n]either the United States Supreme Court, nor the Supreme Court of Virginia has addressed this issue.” City of Chesapeake, et. al., v. Lasting Beauty, LLC, et. al., Chancery No. 04-626, Memorandum Opinion p. 5 (Chesapeake Cir. Ct. March 23, 2006) (hereinafter “Memorandum Opinion”). Thus, this case presents an opportunity for this Court to provide definitive direction where none currently exists. Moreover, this case has implications not only for tattooing in the City of Chesapeake, but potentially for regulating other forms of expression by localities throughout the state. Amicus respectfully urges this Court to grant the Petition for Review in order to determine whether it is constitutionally permissible for localities (and their courts) across Virginia to emulate the City of Chesapeake in regulating artistic expression. ARGUMENT Amicus believes that review of this case is amply warranted by several errors in First Amendment analysis by the court below. In determining that the Chesapeake ordinance did 4 not implicate the First Amendment, the court below relied heavily on a decision of the South Carolina Supreme Court that upheld a state law permitting only licensed physicians to apply tattoos. Memorandum Opinion pp. 5-7 (citing State v. White, 560 S.E.2d 420 (S.C. 2002)). This reliance is misplaced for several reasons. First, the reasoning of White is fundamentally flawed in that, for First Amendment purposes, it distinguished the “process” of tattooing from the tattoo itself. White, 560 S.E.2d at 423 (“Appellant has not made any showing that the process of tattooing is communicative enough to automatically fall within First Amendment protection.”). In dissent, Justice Waller recognized that such a distinction represented a departure from traditional First Amendment jurisprudence. “In my view, this is akin to saying that an author who is paid a commission to write a book by a publisher, or an artist commissioned to paint a rendering, does not engage in speech, but that the publisher, and purchaser of the painting do engage in speech. I find such an analysis completely untenable.” Id. at 425 n.9 (Waller, J., dissenting). Indeed, the process of creating many an expressive work involves no intent to convey a message until the work is completed. In order to protect the creation of expressive works, the lower court’s reasoning would require that the process of creating be a performance in its own right, apart from the creation. A logical conclusion of this reasoning is that government could make a law unreasonably restricting use of the printing press without implicating the First Amendment. Yet, such a conclusion was rejected by the U.S. Supreme Court when it held that a tax applied only to ink and paper used by newspapers placed an undue burden on the First Amendment rights of the press. See Minneapolis Star Tribune v. Minnesota Comm’r of Revenue, 460 U.S. 575 (1983). 5 The lower court’s reliance on White is also misplaced because the South Carolina Supreme Court itself relied heavily on cases that failed to view tattooing in its proper context. As Justice Waller notes in his dissent, in the time since the cases relied upon by the majority were decided the cultural status of tattoos has increased while serious health risks have diminished. See White, 560 S.E.2d at 425 (Waller, J., dissenting). Citing the increase in mainstream popularity of tattoo art and its acceptance in respected galleries and scholarly institutions, Justice Waller concludes that, “Consistent with the more modern trend, it is my opinion that the process of tattooing is indeed a protectable form of speech.” Id. at 425.1 In addition, the White majority failed to consider the lengthy and detailed analysis provided in Lanphear v. Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Mass. Superior Court Slip Opinion 99-1896-B (October 20, 2000), aff’d, Commonwealth v. Lanphear, 50 Mass. App. Ct. 1107, 737 N.E.2d 1281 (2000) which concluded tattooing was protected by the First Amendment. See also MacNeil v. Bd. App. Boston, No. 02CV01225, 2004 WL 1895054 (Mass. Super. Aug. 8, 2004). The mere fact that there is a split among other jurisdictions on 1 In his dissenting opinion, Justice Waller quotes the following synopsis: The cultural status of tattooing has steadily evolved from that of an anti-social activity in the 1960s to that of a trendy fashion statement in the 1990s. First adopted and flaunted by influential rock stars like the Rolling Stones in the early1970s, tattooing had, by the late 1980s, become accepted by ever broader segments of mainstream society. Today, tattoos are routinely seen on rock stars, professional sports figures, ice skating champions, fashion models, movie stars and other public figures who play a significant role in setting the culture's contemporary mores and behavior patterns ... The market demographics for tattoo services are now skewed heavily toward mainstream customers. Tattooing today is the sixth-fastest-growing retail business in the United States. The single fastest growing demographic group seeking tattoo services is, to the surprise of many, middle-class suburban women. Tattooing is recognized by government agencies as both an art form and a profession and tattoo-related art work is the subject of museum, gallery and educational institution art shows across the United States. "The Changing Cultural Status of Tattoo Art" (http:/ www.tattooartist.com/history.html); See also Lawrence Muhammad II, Tattoo You, Chicago Tribune (Nov. 4, 1997)(recognizing that tattoos have begun to appeal to people from every walk of life, and that, contrary to popular belief, there is no serious health risk involved in getting a tattoo, either. In most tattoo parlors, needles and inks are single-serve, gloves are worn and other utensils are steam/autoclave-sterilized, the same method used by hospitals for surgical equipment). 6 this issue warrants this Court’s granting the Petition for Appeal in order to provide definitive direction to the localities and citizens of Virginia. This Court should also hear the case in order to insure that Virginia courts apply the analysis of United States v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. 367, 377 (1968) when determining the constitutionality of content-neutral laws that nonetheless place burdens on the exercise of expressive activity. (See Satellite Broad. & Commc'n Ass'n v. FCC, 257 F.3d 337, 355 (4th Cir. 2001) (law at issue is "a content-neutral measure that imposes incidental burdens on speech and is therefore subject to intermediate First Amendment scrutiny under United States v. O'Brien")). O’Brien holds that “a government regulation is sufficiently justified if it is within the constitutional power of the Government; if it furthers an important or substantial governmental interest; if the governmental interest is unrelated to the suppression of free expression; and if the incidental restriction on alleged First Amendment freedoms is no greater than is essential to the furtherance of that interest.” O’Brien, 391 U.S. at 377. Yet, the lower court failed to apply or even mention the O’Brien standard in assessing the Chesapeake ordinance. Instead, the lower court merely dismissed First Amendment concerns by claiming the act of creating a tattoo was pure conduct, arguing that under the holding of Spence v. Washington, 418 U.S. 405 (1974), the “Defendants were required to show how the act of tattooing or applying permanent makeup is intended to convey a particularized message and whether there is a likelihood that the message would be understood by those who viewed it." Memorandum Opinion p. 7. But this interpretation of Spence is at odds with subsequent U.S. Supreme Court holdings on the issue. For example, in Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Group of Boston, the Court stated a “narrow, succinctly articulable message is not a condition of constitutional protection, which 7 if confined to expressions conveying a ‘particularized message,’ cf. Spence v. Washington, 418 U.S. 405, 411, 94 S.Ct. 2727, 2730, 41 L.Ed.2d 842 (1974) (per curiam ), would never reach the unquestionably shielded painting of Jackson Pollock, music of Arnold Schöenberg, or Jabberwocky verse of Lewis Carroll.” Hurley, 515 U.S. 557, 569 (1995) (citation to Spence in original). Given the lower court’s complete silence both on the U.S. Supreme Court’s elaboration of its the holding in Spence, and its holding in United States v. O’Brien, amicus urges the granting of the Petition of Appeal in order to allow this Court to fill that jurisprudential void. CONCLUSION For the foregoing reasons, amicus curiae urge this Court to grant the Petition for Review filed by the Petitioners / Appellants. Respectfully submitted, ______________________ J. Joshua Wheeler VA State Bar # 36934 Counsel for Amicus Curiae The Thomas Jefferson Center for the Protection of Free Expression 8