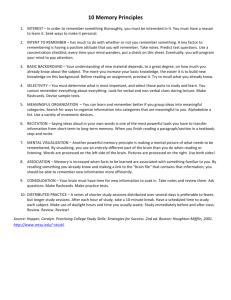

An Essay on Existentialism Yavor Stoychev In this

advertisement

An Essay on Existentialism Yavor Stoychev In this essay, I will investigate two contrasting ideas about the nature of human existence and its meaning. I will start by presenting the ideas of Thomas Nagel, who believes that life is fundamentally absurd. I will list the three common, but according to Nagel, false views on the origin of absurdity. I will then present Nagel's own idea about the source of absurdity in life, and explain why, according to him, there is no way out of it. I will also clarify why Nagel believes that the absurd occurs only in the life of a human being. I will continue by examining Richard Taylor's views on the meaning of human existence. I will explain why he believes that most people lead lives that are as meaningless as the life of Sisyphus. I will then present a modified version of the myth of Sisyphus, in which, according to Taylor, Sisyphus still does not lead a fully meaningful life. I will conclude this part of the essay by expanding on Taylor's ideas about bringing meaning to human life, and explain why he believes that most people cannot lead meaningful lives. Afterwards, I will determine whether I find Susan Wolf's criticism of Nagel and Taylor accurate. To do so, I will present the features that bring meaning to life according to Wolf. I will then examine the case of the modified myth of Sisyphus and explain why Wolf believes that Sisyphus's life is not meaningful in this scenario. To conclude, I will present my own opinion on whether Wolf's arguments show that life is neither absurd, nor meaningless. In his article “The Absurd”, Thomas Nagel argues that human existence is ultimately absurd. To make his point, he first presents three different misconceptions (in his opinion) about the origin of the absurd. He presents the idea that none of our deeds matter if we look far enough into the future. He states that this line of thought is wrong, because our present concerns are absurd regardless of whether our deeds matter a million years from now. Nagel then examines a second argument – that “we are tiny specs in the infinite vastness of the universe”, and that our lives are mere instances on a cosmic scale. He argues that even if we lived forever, and were big enough to fill the universe, that wouldn't make our life any more meaningful. The third argument that Nagel discusses claims that life is an elaborate journey leading nowhere, and even if one's life has an effect on other people, that effect will end with their deaths. Nagel states that life is not just a sequence of activities, which has its purpose somewhere later in the sequence, and these chains often break within a lifetime. He also claims that things in life that we consider self-justified, lead to a chain of justification that is never complete, and in reality these justifications do not transcend the human lifespan. Although he disproves these explanations for the absurdity of life, Nagel does not dispute absurdity, but rather wants to start off with a clear ground on which he wants to build his own arguments. In Nagel's terms, absurd refers to a “conspicuous discrepancy between pretension or aspiration and reality”, and gives us some examples of absurd situations – a complicated speech in support of a motion that has already been passed, a notorious criminal made president of a major philanthropic foundation, and two others. In any case, once an absurd presents itself, people might not necessarily be willing or able to bring their aspirations and pretensions in line with reality. According to Nagel, human do not act solely on instinct. He believes that we can view ourselves from two distinct perspectives – the lived perspective, and, by stepping back and looking through the eternal perspective (which Nagel calls the “sub specie aeternitatis”). This perspective lets us realize that we can regard everything in this world as arbitrary and open to doubt and, nevertheless, we take our lives seriously, and we feel a sense of reward for doing so. Nagel states that these two viewpoints collide in us, and this is the origin of absurdity in human life. He argues that we cannot help viewing ourselves seriously, even though we realize that we have every reason to be skeptical. He points out that we take ourselves seriously because we care about our own survival, regardless of whether we have any higher pursuits, and that this is inescapable. Nagel continues by examining the idea that one might escape from the absurd by seeking broader ultimate concerns in terms of a function in something larger. He gives examples of people serving society, God, or the empty stomach of a human-eating creature, and points out that any such larger purpose can be put in question much the same way as the aims of an individual life. He claims that we can step back and doubt God, society, science, in much the same way as we doubt our instincts and personal goals, and that the only thing that “ultimate concerns” change is the scale on which we look at things, but all of the conclusions made earlier still hold. Before addressing the question of how we should “deal with” the absurd, Nagel presents us with two entities, whose existence is not absurd – the life of a mouse, and the orbit of the moon. The orbit of the moon has nothing absurd to it, because “it involves no strivings or aim at all”, while human beings strive to survive, at least. A mouse, just like a human being, fights for its survival. However, it does not possess self-consciousness and self-transcendence, and thus it does not realize it is only a mouse. Thus, a mouse is not absurd, because it cannot view itself from the eternal perspective, and there's no clash. If, however, a mouse were able to view itself from the eternal perspective, it would be absurd. This begs the question whether humans can avoid the absurd by refusing to view themselves from the eternal perspective, and the Nagel concludes that this cannot be achieved by the will. The questions remains: how to deal with the clash between the eternal and the lived perspective, and the absurd it represents? Nagel believes that philosophical skepticism should not make us stop eating or breathing. It should not make us denounce who we are, but rather bring a “peculiar flavor” to our ordinary beliefs, while we go back to our small and meaningless pursuits. Nagel's idea of how to deal with the absurd is radically different from Camus's because it doesn't treat absurdity as a problem and a threat to our dignity, but rather “a manifestation of our most advanced and interesting characteristics”. Nagel regards the “defiance or scorn” proposed by Camus as pointless and dramatic. In his article “The Meaning of Human existence”, Richard Taylor argues that most people live meaningless lives. He starts by saying that simply being alive is not meaningful, He believes that animals do not lead meaningful lives, because they are driven by instincts, and humans are only superficially different. Taylor describes a meaningless life as a life that is repetitive and lacks purpose. He gives the example of Sisyphus, who would push a stone up a hill forever just to see it fall down again. He continues by pointing out that meaning has nothing to do with justice and happiness. He claims that, as far meaningful life is concerned, most people are just like Sisyphus. Richard Taylor opposes Camus's view that believing that what we do is meaningful brings meaning into our lives. Rather, he believes that most people live in constant self-deception, linking meaning to happiness, romanticizing their lives, and escaping boredom in ways that are as meaningless as a good party or a fun weekend in the mountains. Taylor provides us with three concrete criteria for leading a meaningful life: one should pursue goals in a self-directed and creative fashion; one should pursue goals that a real, and achieve them. According to Taylor, if one is just doing their part without any kind of creativity and self-direction, this does not make their lives meaningful, because one is just a tool in the hands of their master. To demonstrate the concept of creativity, we can use a version of the myth of Sisyphus, in which Sisyphus would push countless stones that would stay up and become a foundation for a magnificent indestructible temple. In this universe, Sisyphus still does not lead a truly meaningful life. He does not push the stones because he really wants to, but because the Gods want him to – he lacks creativity, which Taylor thinks of in terms of a state of mind. But even if one pursues goals with all their creativity and zeal, this is till not enough. According to Taylor, the goals pursed must be real. He gives the example of nuns, who really believe in God, but God does not exist. In this scenario, the nuns still do not live a meaningful life, because, although they might be self-directed, and might believe they are doing something great and beautiful, this is clearly wrong if there is no God. But even if God existed, if the nuns kept praying and praying, and the result of their prayers never came, their life would still not be meaningful. Why? Because, according to Taylor, the goals must be achieved. The very idea of pursuing goals that can never be achieved makes the whole exercise meaningless, as there is no real result, and this is as close as the definition of meaninglessness as we can get. Pursuing a goal that can be achieved, but falling short of it is also meaningless. Under these criteria, Taylor reaffirms his position that very few people live meaningful lives. He observes that often the happiest people lead the most meaningless of lives. And most people strive for happiness. Many people do not do what they want in life, but just blindly follow the commands of their boss, team lead, or manager, or are just prevented by fate from achieving the goal they so eagerly fought for. A scientist can lose the meaning of their life's work if somebody makes that amazing discovery before they do. Taylor believes there is much we can do to bring meaning to our lives, but sometimes fate might not give us a chance to do so. In her essay “The meaning of lives” Susan Wolf presents a different view of what makes life meaningful. Her criteria are not as “harsh” as Taylor’s and Nagel’s and she argues that there are more ways in which we can make our lives meaningful. Much like Nagel, she starts here essay by first arguing what makes life meaningless. She presents us with four examples of a life that lacks meaning – the life of “The Blob”, “The Useless”, “The Bankrupt”, and “The Bored Housewife”. “The Blob” is a person who puts a lot of effort in his job, and comes home to relax by watching TV and drinking beer. Wolf considers this a typical example of a meaningless life – a life that is passive, unconnected, and leading nowhere. “The Useless”, a company executive that works tirelessly for the sole purpose of acquiring wealth, is just as meaningless – while there is a clear dominant activity, Wolf argues that it is pointless and empty. “The Bankrupt” – a person who passionately pursue a goal, just to see his project fail at the last moment – also leads a meaningful life, because, according to Wolf, they spent too much time on a failed project. The last example – the “Bored Housewife” is an example of somebody who is active, but not “actively engaged” – she simply goes through the motions, without pursuing any kind of inner calling. After summing up her arguments for the lack of meaning in these examples, Wolf provides us with a definition of what she would consider a meaningful life as characteristics that are not present in any of the four examples of meaninglessness – “a meaningful life is one that is actively and at least somewhat successfully engaged in a project (or projects) of positive value. Wolf recognizes that the terms used in these proposals are rather broad, and tries to refine them. She starts by defining “projects” as activities that are not necessarily goal-directed, but can also refer to relationships and other activities that we might not take on deliberately. Then Wolf focuses on the definition of “positive value”. She does not give criteria that determine objective goodness, but she believes that there must be objective standards on which we can base our judgment. She agrees with Taylor, that believing that something is meaningful doesn’t make it so, because allowing this will remove the difference between striving to lead a meaningful life and striving to lead a life that seems meaningful. She also claims that if one suspects their life might not be meaningful, merely changing their opinion, but continuing to lead their life in the same fashion will not bring meaning into their lives. In this respect, Wolf would disagree that if Sisyphus were injected with a substance that makes him feel great about rolling stones up a hill, his life gets any more meaningful, because adopting an attitude that transforms an objectively meaningless act into a meaningful one does not bring true meaning to one’s life. Wolf’s views of meaning are quite different from those of Nagel and Taylor. Nagel believes that life is utterly meaningless and absurd, and there is no escape, but it’s ok, and we can all have a good laugh about it, and then keep going. Taylor believes that there is a way to live a meaningful life, but most people don’t try, don’t care, do it wrong, or never get the chance. He believes that very few people do it right, and bringing meaning to one’s life requires a complete and single-minded devotion to a “real” goal and achieving it. He thinks of meaning as something that stems from a truly spectacular achievement, and that as long as there is active participation and creativity involved, the attitude of the person doesn’t matter. Wolf thinks that attitude does matter. In fact, she thinks that meaning cannot exist if the person does not truly think that what they do is meaningful. She also thinks that life has moments of meaning, as opposed to a final pass/fail grade in the end, and that if you had meaning at least once, your life is meaningful. After reviewing the three essays, I must say that I do not find Wolf’s arguments against Nagel’s views on absurdity and Taylor’s views on meaning convincing enough. Wolf herself acknowledges the existence of the absurd, as defined by Nagel, and her proposal for dealing with it does not significantly differ from Nagel’s “ironic” approach – both of them agree that the absurd is not a real problem, and that we should not panic or get disappointed, but rather acknowledge it and continue to live our lives unaffected. But Wolf tries to argue that both Nagel and Taylor are “harsh graders” when it comes to the meaning of life. Taylor and Nagel would argue that the only objective measure we have is the perspective of eternity. Wolf, however, believes that a community can bring objectivity to an action and thus make it meaningful. Yet I fail to see how, if a person’s opinion can be subjective, a community of individuals can be relied on to be objective. From a more “mathematical” perspective, this might be true if the community is infinitely large, and has infinite diversity. But real communities are not like that. They are a rather homogeneous group of people with similar tastes who think alike. Sometimes intense communication can occur inside a community, while it remains relatively isolated from the rest of the world. I believe that in such a case, a community becomes closer to what we regard as a “sect”, and no objectivity can be expected from it. In this essay, I presented the two perspectives that, according to Thomas Nagel, clash to cause the absurd in human life, and shown why this clash does not occur in other animals and inanimate objects. I also pointed out what Nagel believes to be the appropriate response to this absurd. Next I presented Richard Taylor’s idea about the meaning of human existence, and, through discussion and alteration of the myth of Sisyphus, showed what the two main characteristics of a life that is not meaningful, and then listed the three features that must be present to bring meaning to life and explained why each of them is necessary according to Taylor. Finally, I discussed Wolf’s criticism of Nagel and Taylor. I presented the features that Wolf finds necessary for a meaningful life. I examined her views on the modified myth of Sisyphus, and explained why his life is not meaningful according to Wolf’s criteria. Finally, I provided my own arguments against Wolf’s idea of objectivity, and concluded that her analysis fails to see that a community can be subjective.