LAW & ECONOMICS RESEARCH PAPER SERIES Sponsored by

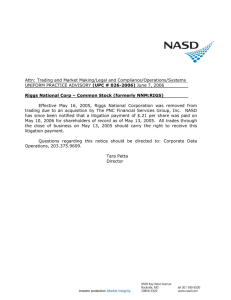

advertisement