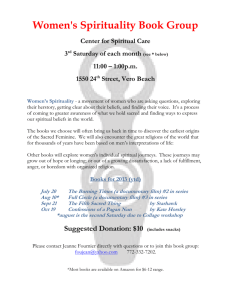

Life Cycles and Spirituality

advertisement