Thomas Hardy - Broadview Press

advertisement

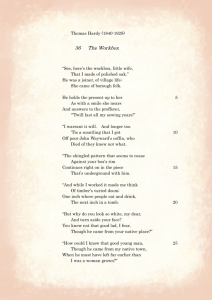

Thomas Hardy Possible Lines of Approach Hardy the Victorian Hardy as modernist poet The significance of fate Representations of women Hardy’s biography Notes on Approaching Particular Works Jude the Obscure “Hap” “The Ruined Maid” “The Convergence of the Twain” “Channel Firing” “In Time of ‘The Breaking of Nations’” “The Voice” “During Wind and Rain” Questions for Discussion Critical Viewpoints / Reception History Links Possible Lines of Approach Hardy the Victorian Hardy came to prominence as a novelist during the Victorian period. Though Hardy’s interest lay mainly in poetry, he believed fiction would be a more profitable enterprise; starting with his first successful novel, Far from the Madding Crowd, published in 1874, Hardy proved himself remarkably prolific, authoring 11 more novels and three collections of short stories, ending in the publication of Jude the Obscure in 1895. Hardy’s fiction is in the realist mode; as such, it captures the Victorian era, particularly as it is lived by the working class in rural areas. At the same time, Hardy challenges Victorian norms and mores, frequently offending Victorian sensibilities. In particular, his last two novels—Tess of the D’Urvervilles and Jude the Obscure—were the subject of scandal. (Hardy, in fact, abandoned novel writing after the Jude controversy, turning fulltime to poetry.) Jude the Obscure (an excerpt—Part 3, Chapter 4—is included in The Broadview Anthology of British Literature’s Victorian volume in “Contexts: Religion and Society”) furnishes a good opportunity for studying Hardy as a Victorian author, for it represents Victorian concerns, focusing on the lived reality of Victorian lives, all the while exposing the fundamental hypocrisy of Victorian social institutions and customs. You may wish to note that, while certainly Victorian in many respects, Jude also anticipates modernism, particularly in its frankness about sexuality, its concern with modernity, and its depiction of what Hardy termed “the ache of modernism” in Tess of the D’Urbervilles (Tess’s melancholy is described as “feelings which might almost have been called those of the age—the ache of modernism” in “Phase the Third” of Tess.) Hardy as modernist poet After the scandal caused by the publication of Jude the Obscure in 1895, Hardy abandoned novel writing and focused on poetry. He is considered by many scholars to be an important forerunner of the development of a modernist poetics. The unusual syntax and the sense of uncertainty and doubt, characteristic of much of Hardy’s poetry, anticipate and build on early twentieth-century developments in poetry. Though many of the poems deal with the past, their forms echoing the archaic ballad, Hardy’s concerns—war, a rapidly changing world, fear in the face of the unknown—evoke the excitement and the dread of modernism and modernity. In taking this approach, you should be sure to note that many critics have seen Hardy’s poetry as a reaction against modernism. In this view, Hardy is very much a poet of the past, both in subject matter and form. His interest in the rural, the agricultural, can also be understood as a repudiation of the more urban modernism. Much of the poetry is marked by simplicity, by straightforwardness, and this too stands opposed to the most common definitions of what constitutes modernist poetics, particularly as propounded and practiced by Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot. Ultimately, you may want to have students decide the case, particularly if you are teaching Hardy in the context of a survey class. How does his poetry depart from typically Victorian verse? How does it differ from high-modernist poetry? What is Hardy’s place in the tradition of British letters? The significance of fate Fate is a persistent theme in Hardy’s work. The world as depicted by Hardy is ruled by cruel chance, by randomness, by swift retribution for the guilty and the innocent. A sense of doom hovers over characters like Jude Fawley and Sue Brideshead, damned by a family history of tragic marriage; but, like the inhabitants of Greek myth, Jude and Sue’s attempts to subvert familial destiny only propel them toward their fates. But though critics have accused Hardy of pessimism, of excessive hopelessness, it is also possible to see Hardy as an astute social critic, an author ultimately interested in the social constraints and limitations that bind his characters and lead them to tragedy. Natural forces interfere, making playthings of man, but these are no match for the more powerful, more insidious forces unleashed by disapproving, hypocritical society. In “Thomas Hardy’s Tragic Hero” (Nineteenth-Century Fiction 9 [1954-5]: 179-191), Ted R. Spivey defines tragedy in Hardy’s novels as “the defeat of the romantic hero’s desire to reach a higher spiritual state. The drives of Hardy’s characters to achieve states of love and ecstasy are powerful enough to make his chief characters among the most passionate in English literature.” Spivey further posits that Hardy’s protagonists defiantly struggle against their fates, but are ultimately forced to accept doom, although they are also granted insight into their downfalls . Thus, in discussing Jude the Obscure, you may wish to ask students to consider the extent to which Jude is fated to tragedy and the extent to which his own actions bring it about. What insights is Jude granted at the end? “Hap” might serve as a fitting introduction to the importance of fate as an aspect of Hardy’s work. You may also want to stress Hardy’s loss of faith—as well as the more general phenomenon of the “loss of God”—as a potential key to understanding Hardy’s vision of a world ruled by inexorable, implacable chance, doling out misfortune, of life determined by “Crass Casualty” (11) and “purblind Doomsters” (13). Representations of women Perhaps the most notorious portrait of a woman in Hardy’s work is to be found in Tess of the D’Urbervilles, whose eponymous heroine caused a scandal. Hardy’s insistence that Tess remains pure—he subtitled the novel “A Pure Woman” and used an epigraph from Shakespeare’s Two Gentlemen of Verona (“Poor wounded name! My bosom as a bed / Shall lodge thee”) as a testament to Tess’s “good name”—did little to assuage the outrage of most reviewers, who found the novel’s frankness shocking and its heroine immoral. More recently, scholars have tended to focus on Tess’s physical appearance, the repeated descriptions offered by the narrator, who seems, at times, fascinated by Tess’s red mouth and her bosom. Tess’s beauty quickly reveals itself as her downfall, her burden, her fatal flaw; in one particularly notable scene, Tess attempts to mutilate herself, to undo her attractiveness, a source of much pain to her. The case of Tess suggests the complexity of Hardy’s depictions of women: on one hand, he is a sympathetic, sensitive voice, a defender of women, a champion of their rights and causes; on the other, his female characters are often most notable for their physical charms, the very attractiveness that seems to threaten them. In this way, they seem even more menaced by fate, more doomed to unhappiness and misery and suffering than their male counterparts. Jude the Obscure is particularly instructive here: ask students to carefully consider the portrayal of Jude and Sue; how might their respective representations, their feelings, thoughts, and actions, be gendered? Also of interest here is the question of Sue’s “New Woman” status. Is she ultimately a New Woman? A feminist ideal or a stereotype, an embodiment of late-nineteenth century fears about degenerate femininity? What is to be made of her fear of sex, her revulsion at intimacy? Consider as well “The Ruined Maid”: what does the poem suggest about sexuality, about women, about social views of the two? Hardy’s biography Much critical writing about Hardy has focused on his biography, attempting to connect personal experience to ideas and style, to establish parallels between Hardy’s life and recurrent themes in his writing. For example, Hardy’s frequent depictions of ill-matched, unhappy marriages, as between Jude and Arabella, have been viewed as arising from his own difficult, disintegrating marriage to Emma Gifford. It is tempting, too, to see Jude Fawley as a surrogate figure for the author, who also dreamed of a university education but was not able to attain it. Jude’s frustrations suggest a nightmare parallel life of thwarted intellectual ambition and passion; although it would be misguided to read the novel—indeed, any of the work—as strictly autobiographical, Hardy seems to have been very deeply invested in Jude, and the harsh reviews that greeted the novel strongly contributed to his decision to cease writing fiction. In taking this approach, you might also want to focus on the poetry, for many of Hardy’s best poems are deeply personal, but not necessarily autobiographical. Though Hardy’s first marriage seems to have been a difficult one in many respects, after Emma’s death he wrote several poems inspired by his life with her. Some critics have also noted that Hardy’s turn to poetry came as the difficulties in his marriage intensified, and his increasing estrangement from Emma (as well as an apparently unrequited attachment to Florence Henniker, a married writer whom Hardy advised) appears to have contributed to his decision to abandon novel writing. Notes on Approaching Particular Works Jude the Obscure Form: Novel. Background/Approaches: Jude the Obscure represents, in a number of significant ways, the culmination of Hardy’s career as a novelist. Jude deals with several concerns central to many of Hardy’s earlier novels; in particular, the sense of doom, of lives determined by cruel fate, the constraints of class and of religion within a rapidly modernizing society arguably reach their apotheosis in this, the last of Hardy’s novels. That Jude coupled these thematic elements with a frank depiction of sexuality and a scandalously unwed couple caused a controversy; in perhaps the most glaring example of the disapproval the novel met with, the book was publicly burned by the Bishop of Exeter shortly after its publication in 1895. (You may wish to note here that Jude was first serialized in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine from December 1894 until November 1895, appearing simultaneously in England and America. Running first under the title The Simpletons, and then Hearts Insurgent, the novel was, as Hardy’s preface to the first edition of the novel indicates, “abridged and modified,” extensively bowdlerized at the insistence of the magazine’s editors who wanted a number of revisions—some minor, others significantly altering the plot—to make the work morally acceptable; the volume version of the novel appeared in November 1895, restoring [for the most part, though not entirely] Hardy’s original vision of the novel.) The harsh reception—one reviewer referred to the novel as “Jude the Obscene”—seems to have been at least partially responsible for Hardy’s decision to stop writing novels; indeed, for the rest of his life, Hardy focused on poetry writing. Jude the Obscure is the story of Jude Fawley and his thwarted attempts to become a scholar and to find love. A village stonemason, Jude dreams of studying at Christminster (modeled on Oxford), but abandons the dream after he is manipulated into marrying Arabella. The marriage is unhappy, doomed by Arabella’s vulgarity; two years into the miserable union, Arabella deserts her husband. The abandoned Jude returns to his home village, where he meets his cousin, Sue Brideshead, and falls in love with her. Sue, however, soon marries her former schoolteacher, Mr. Phillotson, though she is in love with Jude. The marriage is undone by Sue’s revulsion toward sexual relations with her husband, and she eventually leaves her husband to live with Jude. That relationship remains chaste for a period of time, but Jude eventually persuades Sue to sleep with him, and they soon have two children. Haunted by a history of tragic marriages in the family, afraid that the institution of marriage will corrupt their love, Jude and Sue simply live together, alongside their children, as well as Jude’s son from his marriage to Arabella. Their relationship is seen as scandalous: Jude is repeatedly dismissed from the jobs he finds, and the family is frequently evicted by the landlords who learn the truth about the situation. Overhearing Jude and Sue argue one night, Jude’s oldest son strangles the two younger children and then kills himself. This causes Sue to suffer a religious crisis, and she returns to Phillotson. Jude, distraught and broken, re-encounters Arabella, who again tricks him into marrying her. Attempting to see Sue one last time, Jude goes out in terrible weather, becomes gravely ill, and dies, while his wife is out courting his doctor. The very brief summary above is of course woefully inadequate in suggesting the complexity and the scope of Hardy’s achievement in Jude the Obscure. Here we see the working of fate, that seemingly random yet inexorably unstoppable doom binding the life of our hero. Try as he might, Jude cannot and will not succeed; his lot is a tragic one, trapping him at every turn. But the novel makes clear that “fate” is not simply an outside force, the cruel hand of an unfeeling deity or the mystical workings of a supernatural order; rather, Jude is doomed by the constraints of class, by the conventions of social mores, by the demands of religion, by Victorian attitudes about sex and love and marriage and family. Jude’s dream of scholarship is unattainable, and his striving after Christminster is tragic from its very inception. His mistake in marrying Arabella cannot be undone, even after she has abandoned him, while his relationship with Sue is doomed not only by family history, but also by Sue’s feelings about sex and her religious bent. The love Jude and Sue share is undone by its existence in a world full of judgment, which in turn propels their children to their deaths. Given the sense of inevitability, of unavoidable doom, how are we to read Jude and Jude? Ask students whether they view Jude Fawley as a tragic hero. What might be his tragic flaw? Is he a victim of his society? Of the women he loves? Or is he complicit in his own suffering? What is the role of sex and sexuality in the novel? How does the interaction of sexual repression and sexual desire lead to tragedy? What is the role of class? (Make sure to note that Jude is the first major British novel with a working-class hero, a protagonist who is decidedly not genteel.) Finally, let students know that Hardy seems to have drawn on his own experiences in composing Jude the Obscure; how might this fact alter our reading of the novel, our perception of its depiction of doomed destiny? You may also want to address the form and style of the novel. While most critics and Hardy scholars in the 1970s were inclined to view Jude the Obscure as the last major Victorian novel, in the past 30 years many have come to see it more properly as a modernist enterprise. Ask students to locate the novel within a tradition, a literary period; where does it seem to belong? How might it be understood as a transition, a text that observes Victorian conventions while anticipating modernism? What about the novel seems particularly Victorian? What seems modernist? Connections: Jude the Obscure is a strikingly allusive novel, referencing Shakespeare, Milton, and Bunyan, as well as Hardy’s contemporaries Browning and Swinburne, notes Norman Page (see the Norton Critical Edition of Jude the Obscure, 1978); you may find it productive to trace some of these references, to consider Jude’s place in the context of English literature. The literary references certainly seem to have significance, to particularly resonate in a novel so concerned with the thwarted desire for education. Consider as well teaching the novel alongside Hardy’s poetry. There are clear parallels to a poem like “Hap,” which also emphasizes the role of fate, the lack of a benevolent force, and the inevitability of misfortune. A still richer connection to the poetry exists beyond thematic parallels, for Hardy’s novelistic technique is often notably lyrical, often quite poetic. Have students consider the use of poetic tropes in Jude; how do certain formal elements common to Hardy’s poetry function in the novel? “Hap” Form: Shakespearean sonnet; that is, the rhyme scheme is abab cdcd efefgg. Background/Approaches: Though written around 1866, “Hap” was not published until 1898, when it was included in Wessex Poems and Other Verses. You may want to begin by asking students to comment on the poem’s title; what is the meaning of “hap”? It may be useful to have students consult the Oxford English Dictionary, to track the meaning of the word, especially as it would have been used at the time of the poem’s composition. How do the connotations of “chance” and “misfortune” illuminate and emphasize the poem’s themes? It may be particularly useful to consider “Hap” as a key to understanding Hardy’s worldview, the vision embodied within his work, particularly novels like Tess of the D’Urbervilles and Jude the Obscure. Ask students, too, to consider the poem’s form. “Hap” is a sonnet, dependent on a strict use of rhyme and meter, yet its themes, its bleakness, its unremitting refusal of meaning in a world ruled by mere chance seem at odds with the order and sense of the sonnet form. To what ends does Hardy use the traditional form? What does his use of the sonnet suggest about the meaning of “Hap”? How “traditional” is “Hap” as a sonnet? Where, for example, do students locate the sonnet’s volta, its turning point? How well does the concluding couplet resolve or illuminate the sonnet’s themes? In discussing the poem’s concerns, make sure students are familiar with the concerns current at the time of the poem’s composition. J.O. Bailey, for example, has suggested that “Hap” represents Hardy’s reaction to his reading of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, first published in 1859 (The Poetry of Thomas Hardy: A Handbook and Commentary, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1970). How does Darwin’s vision of natural selection, of the survival of the fittest, inform “Hap”? “The Ruined Maid” Form: 24-line poem, in six stanzas of four lines. Each stanza is rhymed aabb; the last line of each stanza ends in “said she.” The poem suggests a dialogue between two young women, with the first three lines of each stanza spoken by one, and the last line spoken by the other. Background/Approaches: You may want to begin by making sure that students understand what is meant by “ruined” in the context of this poem and in the context of the time of its writing (c.1866, at the height of the Victorian period) and publication (in 1901). Note that women could be considered “ruined” or “fallen” for any perceived infraction against propriety, any departure from respectability; indeed, the Victorians often held prostitutes and rape victims in similar regard. Given such a discourse of feminine ruin, ask students to think about how “ruin” seems to be defined in the poem. To what extent does Hardy seem to be working with the conventional definition? Where does he seem to be departing from the convention? Insofar as “The Ruined Maid” has been read as a satire, what might Hardy be satirizing here? Ask students to consider the form of the poem: how does it relate to the contents? What might be the significance of rendering a serious subject in singsong rhyme? What is to be made of the repeated refrain? How does the repetition of “ruined” function here? Connections: Perhaps the most obvious connection is to be made with Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles (1891), a novel very much concerned with the issues briefly satirized in “The Ruined Maid.” The tragic Tess is “ruined” by her association with Alec D’Urberville, an association thrust on her by her greedy, meddling family, and the rest of her life is irrevocably shaped by her experience with Alec. As in “The Ruined Maid,” Hardy questions and challenges the prevailing morality, the conventions that label a woman “fallen” or “ruined,” though she may, like Tess, remain pure, loving, and virtuous in spirit. The fallen woman was an important (and popular) subject in Victorian art, though certainly one that was usually represented in veiled terms; for a more conservative—more stereotypical—depiction than the one offered by Hardy, you could draw students’ attention to William Holman Hunt’s The Awakening Conscience (1853-54), an illustration—albeit a coded one—of a kept woman coming to the realization of her ways. (A reproduction is included in the preface to “The Victorian Era” volume of The Broadview Anthology of British Literature.) You may also want to have students take a look at “The Great Social Evil,” a Punch cartoon by John Leech, which depicts the scenario of Hardy’s poem. Though the cartoon predates the poem by some nine years, and Hardy’s awareness of it is debatable, it is of interest in representing a humorous Victorian perspective of female disgrace. (The cartoon appeared in Punch 33 [10 January 1857]: 114; it can be easily found on the Victorian Web [http://www.victorianweb.org/periodicals/punch/49.html].) “The Convergence of the Twain” Form: 33-line poem, in 11 numbered stanzas; each stanza is rhymed aaa. “Channel Firing” Form: 36-line poem, in nine four-line stanzas; each stanza is rhymed abab. “In Time of ‘The Breaking of Nations’” Form: 12-line poem, in three numbered stanzas; each stanza is rhymed abab. Background/Approaches: “The Convergence of the Twain,” whose subtitle—“Lines on the Loss of the ‘Titanic’”—indicates its commemoration of the drowned Titanic, described before its maiden and final voyage as unsinkable, “Channel Firing,” which notes the preparations for the coming war, and “In Time of ‘The Breaking of Nations,” written during World War I, showcase Hardy as a poet very much engaged with contemporary affairs, with the larger political world. In discussing “The Convergence of the Twain,” you may first want to make sure students are familiar with the story of the Titanic; how does the poem seem to represent both the triumph and the tragedy associated with the doomed ship? What seems to be the speaker’s attitude toward the event? How does the last line of each stanza—significantly longer, disrupting the singsong quality of the rhyme scheme—contribute to the poem’s effect? In approaching “Channel Firing” and “In Time of ‘The Breaking of Nations,’” you might want to begin by asking students about their expectations for “war poems.” How do the two meet these expectations? How do they defy them? Are these clearly poems about specific wars? As you begin addressing these questions, you should have students draw distinction between the two poems: what is each poem’s respective attitude? What does each one suggest about war and about humanity? What is to be made of the techniques Hardy uses in each? How do these techniques—the use of humor in “Channel Firing,” for example—contribute to the overall effect? What is to be made of the use of a simple abab rhyme scheme in poems about war? Connections: A number of war poems, particularly poems dealing with the First World War, could be discussed in conjunction with “Channel Firing” and “In Time of ‘The Breaking of Nations.’” Some possibilities are Siegfried Sassoon’s “They” and “Everyone Sang,” Rupert Brooke’s “The Dead” and “The Soldier,” Isaac Rosenberg’s “Break of Day in the Trenches,” and Wilfred Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est” and “Anthem for Doomed Youth.” “Contexts: War and Revolution” in The Broadview Anthology of British Literature might also be useful in discussing Hardy’s war poems. “The Voice” Form: 16-line poem, in four four-line stanzas; each stanza is rhymed abab. Background/Approaches: Though not published until 1914, “The Voice” was written in December 1912, about a month after the death of Hardy’s wife Emma. Though Hardy and Emma had become estranged, her death grieved him, and he mourned Emma by writing a number of poems about their marriage and his guilt at its unraveling; poems which attempt to celebrate, eulogize, and atone. “The Voice” is representative of such endeavors; here, the speaker—presumably Hardy—hears the woman he once loved—presumably Emma—call to him, and he implores her to appear to him as she once had been, to appear as she appeared during their courtship, only to realize that she is “no more” (12), only a voice he imagines calling him. Because the poem seems to echo Hardy’s feelings, to reflect the circumstances of his life at the time of its writing, try to focus the discussion not on what the poem is about, but rather on the ways it goes about conveying Hardy’s emotions. Ask students to pay attention to Hardy’s use of meter. Why does the regularity of the first three stanzas give way to the awkward, irregular meter? How does the poet use syntax to first evoke hope that the woman may be speaking, only to convey disappointment? “During Wind and Rain” Form: 28-line poem, in four seven-line stanzas. Each stanza is rhymed abcbcda. Background/Approaches: “During Wind and Rain” depicts Hardy’s first wife, Emma, in her childhood, while repeatedly acknowledging the inevitability of death and the destruction wrought by time. The mixture of innocent happiness and its decay evokes the relationship of the Hardys, the happy years of their courtship, followed by the misery and disappointment of the later years of their marriage. As with “The Voice,” the subject of the poem is not likely to inspire much debate. Rather, you will want to direct students’ attention to Hardy’s technique, particularly his use of form and rhythm. “During Wind and Rain” employs a precise pattern, with the first five lines of each stanza depicting a moment of family happiness and the last two lines bemoaning “the years” and their passing. What does the pattern suggest in terms of the poem’s theme? Note, too, Hardy’s use of alliteration: “garden gay” (11), “blithely breakfasting” (15), “clocks and carpets and chairs” (24). What might be the technique’s significance here? Ask as well what students make of the repetitions in the poem, its use of refrain. Questions for Discussion 1. Discuss the significance of fate in Hardy’s work. What is the role of fate in Jude the Obscure? Is Jude condemned to his destiny? To what extent is he free? 2. Discuss Hardy’s depiction of women. Do you see Hardy as a feminist? 3. How do social conventions, social mores and beliefs, function in Hardy’s work? What relationship does Hardy posit between “fate” and the restrictions and demands of society? 4. Discuss Hardy as a Victorian. 5. Discuss Hardy as a modernist. 6. In what ways does Hardy provide transitions between the Victorian and the modernist periods? 7. In what sense is Hardy a “public poet,” a poet engaged with the world around him? In what ways is he a “personal poet”? 8. What poetic techniques, what formal elements, does Hardy make use of? To what end? 9. Discuss the connections between Hardy’s life and his work. 10. How does Hardy make use of intellectual developments of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries? What is the influence of Darwin? Of Freud? Critical Viewpoints / Reception History “Nobody disputes the station of Hardy among the prophets. It is likely that, as a novelist, Hardy will be regarded as our greatest; that, among dramatists, he will be accorded rank as the true successor, but not the copyist, of Shakespeare …; that the unimitative and frequently harsh music of his verse will give him lasting place among English poets.” Such was Edward B. Powley’s opinion of the matter in A Hundred Years of English Poetry (Toronto: Macmillan, 1933, 100). Powley’s assessment suggests not only Hardy’s place in English letters but also articulates the astonishing range of his accomplishments. Novels, short stories, plays, poems: Hardy wrote them all and wrote them all well. How he came to do so and what lies beneath the surface of astounding accomplishment will be the main focus of this review. Originally intending (and preparing for) a career in architecture, Hardy instead devoted himself to writing; though he thought of himself as primarily a poet, he viewed the writing of fiction as more financially practical. His first novel, The Poor Man and the Lady, completed c.1867, failed to find a publisher, but Hardy was encouraged by the advice of George Meredith, a prominent Victorian poet and novelist, who persuaded Hardy to keep writing. His next two works—Desperate Remedies (1871) and Under the Greenwood Tree (1872)—were published anonymously, but by 1873, Hardy was able to publish A Pair of Blue Eyes under his own name. It was the publication of his next novel, Far from the Madding Crowd, in 1874 that began to establish Hardy’s reputation as a writer, allowing him to fully abandon his architectural work in order to pursue a literary vocation. Far from the Madding Crowd is widely considered to be Hardy’s first mature work; it is also the first to introduce “Wessex,” the setting for all of Hardy’s major novels. (The fictional “Wessex” refers to an area in the southwest of England; Hardy chose the name of the medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom that existed in that part of the country before the Norman conquest.) Hardy married Emma Lavinia Gifford in 1874, a match that, at least in the beginning, made Hardy very happy. The next 12 years were a time of great professional success; Hardy was incredibly productive, writing and publishing six novels—including The Return of the Native and The Mayor of Casterbridge, widely considered two of his most important novels—in the period between 1875 and 1886. The list of Hardy’s publications in this period also includes a number of short stories, which were published regularly, beginning with “The Distracted Young Preacher” (1879). But Hardy’s professional triumphs appear to have contributed to problems in his marriage; the deteriorating relationship with Emma is typically viewed as having been profoundly influential in Hardy’s development as an author. Certainly Hardy’s last two novels represent a break of sorts, both in terms of their style and in terms of their reception. Tess of the D’Urbervilles, published in 1891, first as a serial in Graphic and subsequently in three volumes, presented a number of difficulties with editors, who demanded revisions and excisions, and with reviewers, who protested the novel’s “immorality.” Jude the Obscure, serialized from 1894 to 1895 in New Monthly Magazine and published as one volume in November 1895, reignited the controversy, generating a series of harsh reviews. “I do not know … for what audience Mr. Hardy intends his last work,” Margaret Oliphant wrote in Blackwood’s Magazine, labeling the book’s “tendency … shameful” and terming the novel “grotesque” and a “nauseous tragedy” (“The Anti-Marriage League,” January 1896; Oliphant’s review also includes commentary on Grant Allen’s controversial novel The Woman Who Did). In a letter to the Yorkshire Post, the Bishop of Wakefield described himself as “so disgusted with [the novel’s] insolence and indecency that I threw it into the fire” and noted that he considered the work “a disgrace to our great public libraries”; the Bishop’s letter came a day after the Post had published a lengthy denunciation of Hardy on 8 June 1896. Still, a number of critics defended both Tess and Jude as artistic achievements. Edmund Gosse, writing in Cosmopolis (January 1896), called Jude an “irresistible book,” noting censure to be the business of the moralist rather than the critic. D.F. Hannigan, a prominent reviewer and translator, pronounced Jude the Obscure “the best English novel which has appeared since Tess of the D’Urbervilles,” and placed Hardy in the company of “Fielding, Balzac, Flaubert, Turgenev, George Eliot and Dostoievsky” (Westminster Review, January 1896), while Havelock Ellis called Jude “a singularly fine piece of art” which “deals very subtly and sensitively with new and modern aspects of life” (Savoy Magazine, October 1896). It should be noted as well that both Tess and Jude sold well, becoming popular with the reading public in spite of the controversies they generated. Nonetheless, the difficulties Hardy encountered, first in finding publishers, then in the hostility of some reviewers, took their toll, coinciding with an increased strain in Hardy’s marriage and confirming his decision to give up the writing of novels. Hardy’s writing career, however, was far from over. He now (re)turned to poetry, publishing Wessex Poems in 1898. The volume contained about 50 poems, most written in the 1860s, before Hardy became a full-time writer, and the 1890s. Poems of the Past and the Present was published in 1901; the collection was reviewed well and established Hardy as a poet. Hardy devoted some time to revising earlier work, overseeing the publication, in 1912, of the collected “Wessex Edition,” containing the definitive versions of his novels, but poetry writing was clearly his main professional preoccupation in the twentieth century. In 1909, he published Time’s Laughingstock, his third poetry collection. The following year, he was awarded the Order of Merit; he also succeeded his friend George Meredith as President of the Society of Authors. Satires of Circumstances (1914) contains some of Hardy’s most personal poems, addressing his relationship with Emma, who had died in November 1912. Though she and Hardy had been long estranged at the time of her death, Hardy’s grief took him to the places of their courtship, leading him to produce a series of elegiac poems, collectively known as “Poems of 1912-13,” and subtitled Veteris vestigia flammae, or “traces of an old fire.” Satires also includes “The Convergence of the Twain,” a reaction to the sinking of the Titanic in 1912. The collection is thus notable in showcasing Hardy as a poet equally adept at engaging with the personal and the historical, the private and the public. The historical would engage Hardy in subsequent years; during World War I, Hardy wrote a number of poems, later grouped together as “Poems of War and Patriotism,” published in Moments of Vision (1917). Hardy oversaw the publication of his Selected Poems in 1916; the Collected Poems appeared in 1919. Two more volumes of poetry—Late Lyrics and Earlier (1922) and Human Shows (1925)—followed, as did a verse drama—The Famous Tragedy of the Queen of Cornwall (1923). Winter Words (1928), Hardy’s last collection, was published posthumously, as was the fourth edition of the Collected Poems, containing 918 poems. (The poet Philip Larkin once remarked that he would not want Hardy’s Collected Poems to be shorter by even a single page [see Larkin’s Required Writing, New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1983].) In the years since Hardy’s death (on 11 January 1928), his work has been the subject of a number of critical studies. Hardy has long been considered one of the most important English novelists; more recently, his poetry is increasingly admired and studied. Hardy has been influential, an acknowledged inspiration for several important twentieth-century authors, including the novelists Virginia Woolf, Robert Graves, and D.H. Lawrence, whose Study of Thomas Hardy (1936), an unconventional look at Hardy’s influence on Lawrence’s development, remains significant, and the poets Ezra Pound, W.H. Auden, Dylan Thomas, Marianne Moore, and Philip Larkin. Certainly, one potential approach to Hardy is to consider the central role he has played in the development of a distinctly modern aesthetic, to take into account Hardy’s particular accomplishment as a novelist and a poet, a Victorian and a modernist. Another popular approach has been biographical. Biographies of Hardy tend to offer interpretation of his work, as well as background and context for doing so. Robert Gittings’s two-volume biography, Young Thomas Hardy (Boston: Little, 1975) and Thomas Hardy’s Later Years (Boston: Little, 1978), Michael Millgate’s Thomas Hardy: A Biography (New York: Random, 1982), and Martin Seymour-Smith’s Hardy: A Biography (New York: St. Martin’s, 1994) offer comprehensive portraits of the author, as well as considerable consideration of his work; indeed, Millgate is also the author of an important work of Hardy criticism, Thomas Hardy: His Career as a Novelist (New York: Random, 1971). But though it is understandably tempting to connect Hardy’s personal life to his artistic vision, Hardy has also been subjected to a number of more theoretically based studies. Of these, J. Hillis Miller’s Thomas Hardy: Distance and Desire (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1970), which takes a phenomenological approach and identifies “distance” and “desire” as the guiding tropes in Hardy’s novels, Penny Boumelha’s Thomas Hardy and Women: Sexual Ideology and Narrative Form (Totowa: Barnes, 1982), David J. DeLaura’s “‘The Ache of Modernism’ in Hardy’s Later Novels” (ELH 34 [1967]: 380-99), The Sense of Sex: Feminist Perspectives on Hardy, edited by Margaret R. Higgonet (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993), Irving Howe’s Thomas Hardy (New York: Macmillan, 1967), Dale Kramer’s Thomas Hardy: The Forms of Tragedy (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1975), and George Wotton’s Thomas Hardy: Towards a Materialist Criticism (Totowa: Barnes, 1985) are of particular interest. That Hardy continues to inspire critical studies, and that his work lends itself to a wide variety of critical approaches, is yet another testament to the power of his imagination, the extent of his accomplishment, and the place he has come to occupy in the tradition of English letters. Links The Victorian Web [http://victorianweb.org/authors/hardy/index.html] provides a great deal of useful Hardy material, including historical and social contexts, as well as interpretations and discussion questions. The publisher gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Yevgeniya Traps of Queens College, The City University of New York, for the preparation of the draft material.