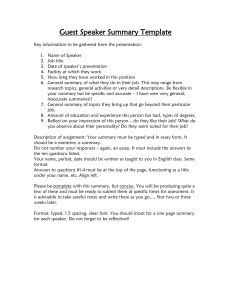

Speaker's meaning

advertisement