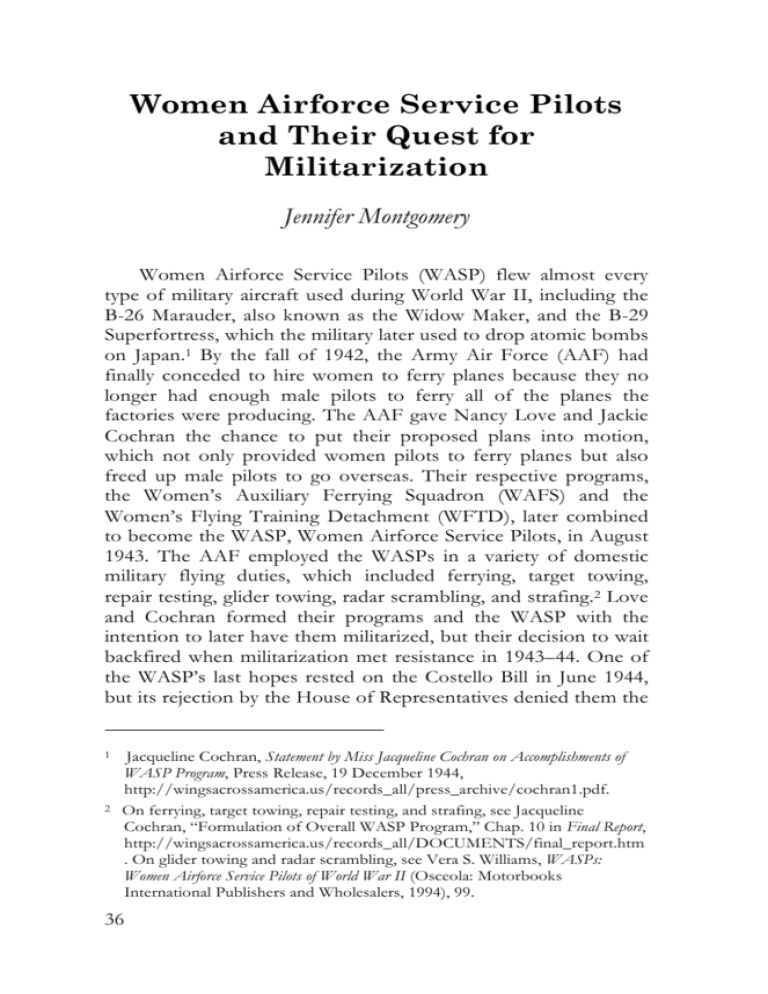

Women Airforce Service Pilots and Their Quest for

advertisement

Women Airforce Service Pilots and Their Quest for Militarization Jennifer Montgomery Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) flew almost every type of military aircraft used during World War II, including the B-26 Marauder, also known as the Widow Maker, and the B-29 Superfortress, which the military later used to drop atomic bombs on Japan.1 By the fall of 1942, the Army Air Force (AAF) had finally conceded to hire women to ferry planes because they no longer had enough male pilots to ferry all of the planes the factories were producing. The AAF gave Nancy Love and Jackie Cochran the chance to put their proposed plans into motion, which not only provided women pilots to ferry planes but also freed up male pilots to go overseas. Their respective programs, the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS) and the Women’s Flying Training Detachment (WFTD), later combined to become the WASP, Women Airforce Service Pilots, in August 1943. The AAF employed the WASPs in a variety of domestic military flying duties, which included ferrying, target towing, repair testing, glider towing, radar scrambling, and strafing.2 Love and Cochran formed their programs and the WASP with the intention to later have them militarized, but their decision to wait backfired when militarization met resistance in 1943–44. One of the WASP’s last hopes rested on the Costello Bill in June 1944, but its rejection by the House of Representatives denied them the 1 2 Jacqueline Cochran, Statement by Miss Jacqueline Cochran on Accomplishments of WASP Program, Press Release, 19 December 1944, http://wingsacrossamerica.us/records_all/press_archive/cochran1.pdf. On ferrying, target towing, repair testing, and strafing, see Jacqueline Cochran, “Formulation of Overall WASP Program,” Chap. 10 in Final Report, http://wingsacrossamerica.us/records_all/DOCUMENTS/final_report.htm . On glider towing and radar scrambling, see Vera S. Williams, WASPs: Women Airforce Service Pilots of World War II (Osceola: Motorbooks International Publishers and Wholesalers, 1994), 99. 36 military status they had hoped for and, even worse, contributed to their deactivation in December 1944 before the war was over. Nancy Love formed the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron in September 1942 with the encouragement of the Ferrying Division of the Air Transport Command within the Army Air Force. She got approval from General Henry “Hap” Arnold, head of the AAF, and sent out telegrams to the most qualified women pilots asking them to report to Dallas Love Field to ferry military aircraft.3 Originally, Love planned for the Woman’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) to commission the WAFS into their organization after a probationary period, which would then make them militarized, but Love soon realized that the WAAC’s congressional bill did not include the word pilot.4 The only way the WAACs could commission the WAFS is if Congress added an amendment to their bill, which would take time. Love and the Ferrying Division were not willing to wait on Congress because they needed to deliver the planes, so they hired the women as civilians and planned to later push for Congress to militarize them under the Army Air Force.5 The decision to organize quickly and start ferrying helped clear out the 3 Helena Page Schrader, Sisters in Arms: British and American Women Pilots during World War II (South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Aviation, 2006), 12. Conflicting information exists for where approval for the WAFS came from, but the mostly likely person it came from was Arnold. For those who say Arnold did not approve it because he was recovering from a heart attack, see Williams, 21–22 and Leslie Haynsworth and David Toomey, Amelia Earhart’s Daughters: The Wild and Glorious Story of American Women Aviators from World War II to the Dawn of the Space Age (New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1998), 43–44. A biography of Arnold, however, says that his first documented heart problem was in March 1943, the next year. Dik Alan Daso, Hap Arnold and the Evolution of American Airpower (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2000), 198. Other sources, such as Cochran’s own writing, say that Arnold never knew about it and someone over him gave approval for it. Recounted in Sally Van Wagenen Keil, Those Wonderful Women in Their Flying Machines: The Unknown Heroines of World War II (New York: Rawson, Wade Publishers, Inc., 1979), 107. 4 On the WAAC, see Schrader, 260. On the use of the word pilot, see Amy Nathan, Yankee Doodle Gals: Women Pilots of World War II (Washington: National Geographic Society, 2001), 21. 5 On not being willing to wait, see Schrader, 260. On planning to push for it late, see Ann B. Carl, A WASP among Eagles: A Woman Military Test Pilot in World War II (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1999), 37. 37 undelivered planes, but it also left the WAFS without military benefits. The pilots in the Women’s Flying Training Detachment did not have military benefits either because Jackie Cochran wanted them to prove themselves first before being militarized.6 Even though Arnold had promised to give Cochran the first opportunity to start a women’s pilot program, she did not get permission to start her own program until after Love had already formed the WAFS.7 Like Love, Cochran was impatient to get started and did not want to wait for Congress to pass any legislation.8 The WFTD was a training program set up to train less experienced pilots, and once women graduated from the program, they joined the WAFS and ferried airplanes.9 Cochran considered the WFTD to be an experiment to prove that women could fly as well as men and serve in the military if needed.10 Even though Cochran did not want the WFTDs militarized in the beginning, she did plan for their future militarization with the structure of the training program. The WFTDs had the same courses and training as male pilots with two exceptions. They did not train in gunnery or formation flying, and they had more instrument training.11 The women lived as if they were in the military by staying in barracks at Avenger Field and keeping them clean to not incur demerits.12 They could also receive demerits while in rank for inattention and chewing gum.13 If they received too many demerits, they washed out of the program.14 The 6 Jacqueline Cochran to the Commanding General, Army Air Forces, C3, 1 August 1944, WASP Virtual Collection, Texas Woman’s University Library. Marianne Verges, On Silver Wings: The Women Airforce Service Pilots of World War II (New York: Ballantine Books, 1991), 42. 8 Ibid., 66. 9 Ibid., 43. 10 Cochran, “Objectives of Women in Pilot Program,” Chap. 3 in Final Report. 7 11 12 13 14 On gunnery and formation flying, see Williams, 84. On instrument training, see Schrader, 54–55. Williams, 71–73. 319th AAFFTD Alphabetical List of Delinquencies and Demerits, p. 4, WASP Virtual Collection, Texas Woman’s University Library. Williams, 73. 38 demerit system shows how their training functioned along military lines even though they were civilians. In contrast, male civilian pilots did not have a demerit system. The female trainees also marched almost everywhere they went, and since they could not talk while marching, they wrote catchy and sometimes brazen songs that expressed their feelings and experiences.15 Once the women graduated, they lived on Air Force bases and flew military aircraft; it seemed only a matter of time before they would actually be in the military. 16 In August 1943, the Army Air Force combined Love’s program and Cochran’s program into the WASP, Women Airforce Service Pilots, because Cochran wanted to branch out into areas other than ferrying. Arnold made Cochran director of the WASP while Love became an executive within the Ferrying Division. Under the WASP, the women pilots continued the same types of military training, and some of them even went through officers’ training in preparation for militarization, which they were hoping would come with the passage of the Costello Bill.17 The Costello Bill would have removed the contradictions the WASPs sometimes faced between their civilian status and military training. One example occurred when an officer walked into a room to ask a WASP a favor. When she realized he wanted to speak to her about flying a plane, she stood at attention. He told her that she did not need to stand at attention because she was only a civilian, yet that was what training had taught her to do.18 The WASPs revealed their feelings about their position within the military in one of their songs called “I’m a Flying Wreck.” Some of the lyrics are: “When the general comes, sir, To view us in our drill, / We’ll do a four winds march, sir, And check out o’er the hill. / And when he calls ‘ATTENTION,’ We’ll click our heels and yell, / ‘I’m just a raw civilian, sir, And you can go to 15 Ibid., 52–53. Williams’ book contains many of the songs the WASP sang. WASP songs can also be found on the following website: http://www.wingsacrossamerica.us/wasp/songs/songs.htm. 16 Cochran to Commanding General, D6, 1 August 1944, WASP Virtual Collection. Verges, 187. Haynsworth and Toomey, 127–28. 17 18 39 HELL.’”19 In the song, the WASPs demonstrate an animosity toward those with military power that they were obedient to and had to treat with military respect even though the female pilots were classified as only civilians. Militarization, which the Army Air Force began to seek around the time they formed the WASP, would have solved the conflicting feelings of the female pilots. By early 1943, the Army Air Force started to make serious attempts at militarization of the WASPs through three main avenues: the WAAC, or Women’s Army Corps (WAC) as it was later known, direct commissions, and legislation; resistance, however, existed against all three. Even though General George Marshall, Chief of Staff of the Army, approved of the WASP militarizing through the WAC, many others within the Army Air Force opposed the idea for various personal and operational reasons.20 Cochran herself completely disliked Ovetta Culp Hobby, head of the WAC, and claimed that she had mismanaged the WACs.21 As director of the WASP, Cochran wanted the women to continue flying and was concerned that Hobby would have them doing other kinds of work.22 Cochran refused to allow the AAF to put the WASPs under Hobby’s command. To Cochran and Arnold, pilots were a different breed and therefore, should not be lumped together with the other groups that fell under the WAC.23 Within the AAF, Arnold and General William Tunner, head of the Ferrying Division, objected to putting the WASP under the WAC.24 The WASPs themselves showed their feelings about militarizing under the WAC in their usual way, through song. In an untitled song, they said “A WAC may be an officer / With bright bars that shine / Her olive green and everything looks fine / She’s very proud of the name she 19 20 21 22 23 24 Williams, 91. Schrader, 139. Verges, 95–96 and Schrader, 138. Williams, 123. Verges, 95–96. On Arnold, see Memorandum to General Marshall from H. H. Arnold, “Incorporation of Women Civilian Pilots and Trainees into Army Air Forces,” 14 June 1943, Jacqueline Cochran and the Women's Airforce Service Pilots Online Documents, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library. On Tunner, see Verges, 180. 40 bears / As for you, you don’t want her cares; / Her olive green was never meant for you, / You want the Santiago Blue.”25 The WASPs did not want to be WACs even if it did mean militarization; they would rather remain civilian pilots for the time being and wear their Santiago blue WASP uniforms. Aside from some of the personal reasons against militarizing under the WACs, operational reasons also existed. In a letter to General Marshall, Arnold listed some of the problems that would require legislation to fix. At this time, WAC legislation still did not include a provision for pilots, and WAC and WASP requirements for membership differed in ways that would negatively affect WASP recruitment. While women could be a WASP from ages eighteen and a half to thirty-two, women had to be at least twenty-one years old to be a WAC, which would restrict some of the WASP’s best flyers.26 With WAC legislation, women could not be a WAC if she had children under fourteen years old, which would again exclude capable female pilots in the WASP.27 The WASP also had their own specific requirements the WACs did not have to meet, such as a certain level of physical condition and flying experience.28 If the AAF had to ask Congress to make changes to WAC legislation, it made more sense for them to just ask Congress for a new piece of legislation that would militarize the WASPs under the Army Air Force instead of the WACs. When the differences between both programs’ requirements were added to the personal animosity Cochran felt towards Hobby, the chance of militarization under the WACs was almost nonexistent. The next method General Arnold attempted to use to militarize the WASPs was to try to direct commission them as officers by using the War Powers Act of September 1941, which gave the Army Air Force the authority to temporary commission officers. Cochran did not think direct commissions were the best choice for the WASPs since women who were training or doing 25 Williams, 7. 26 Memorandum to General Marshall from Arnold, 14 June 1943, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library. Ibid. Schrader, 139. 27 28 41 work other than ferrying could not get them.29 Arnold wrote to the Deputy Chief of the Air Staff to ask if he could give direct commissions to the WASPs, but the Deputy Chief replied that the act only referred to men.30 This interpretation of the act was a setback for the WASPs because it would have been easier to incorporate the women pilots into the AAF this way, at least for the duration of the war, but now the only option left was to get Congress to pass a bill. The Army Air Force’s first attempt to militarize the WASPs with a bill in Congress was in September 1943 with the Costello Bill. The Costello Bill sought to bring the WASPs under the command of the AAF and keep them there for up to six months after the end of the war. The bill first went to the Military Affairs Committee of the House of Representatives where it stayed for six months without discussion of it.31 In February 1944, John Costello reintroduced the bill to the House and Senate with additions that explained officer rankings and gave Congress and the President power to end the use of female pilots sooner.32 The bill did not make any progress in the Senate, but in the House, the Military Affairs Committee held a hearing on it in March.33 General Arnold was in favor of the bill and was the only witness to speak at the hearing.34 The committee members received many letters concerning the militarization of the WASP from male civilian flight instructors and Army Air Force trainees who thought the WASPs were taking their jobs.35 Most of the instructors and trainees had lost their jobs when the Army Air Force closed the Air Force training programs in January 1944 when the Army needed more infantrymen than pilots.36 Arnold told the committee that they should militarize the WASP so that 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 Ibid., 138. Haynsworth and Toomey, 120. Schrader, 139. HR 4219, 78th Cong., 2d sess. (February 17, 1944). Cochran to Commanding General, B2, 1 August 1944, WASP Virtual Collection. Schrader, 140. Ibid., 141. Ibid., 140–41. 42 the women pilots could free up more men for the infantry.37 After hearing Arnold speak, the committee recommended the bill and sent it on to the Rules Committee to pick a day and decide the rules for it to enter the House floor for debate.38 A big debate for the Costello Bill took place once it reached the floor of the House in June 1944 because of the public outcry against it. The civilian instructors and AAF trainees sent even more letters, which the representatives took into special consideration because it was an election year.39 Soon, the press took notice of the debate and picked sides, stirring public fervor even more.40 Although some of the newspapers supported militarization of the WASP, many were against it and printed false stories. They often glamorized the WASPs and blamed them for taking men’s jobs and sending them into the war as ground troops instead.41 The main argument against passage of the bill was that the WASPs would continue to take male pilots’ jobs. However, the WASPs were not taking their jobs because, as Arnold had told the Military Affairs Committee, the Army Air Force would take any men that qualified to fly with them.42 Only about one-third of the instructors qualified, and with the closing of the training programs, the remaining two-thirds were worried about the Army drafting them into the infantry because they were in reserve.43 The trainees were not trained enough to qualify for the AAF, and the Army was not going to train men to fly when what they really needed were ground troops. The smarter choice was to train and use female pilots because they could not fight in the infantry. Those in favor of the bill tried to be heard over the outcry, but not everyone was successful. No one heard the WASPs because Cochran forbade them to write their own letters to the 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 Ibid. Haynsworth and Toomey, 121. Ibid., 129. Verges, 193. Keil, 276. Ibid., 267. Ibid., 267–68. 43 representatives.44 Cochran, however, was working to help the WASPs by massing a huge publicity campaign.45 Arnold was not present during the debates because he was recovering from a heart attack he had in March, and then, he was working on plans for D-Day and helping coordinate the aftermath of it.46 Although support for the bill did exist, it was not as loud as the opposition. More opposition to the Costello Bill came on June 5, 1944, in the form of the Ramspeck Report, which a representative entered into the debate.47 In March 1944, the Civil Service Committee looked into the WASP program to evaluate it and discover where the money came from to fund it since Congress had never approved it.48 Their report, called the Ramspeck Report, focused on the WASPs training and the money the Army Air Force spent on it. Their overall opinion was that the training program was “costly and unnecessary.”49 They recommended that the AAF cancel the training program but said that the female pilots who were already working should continue to do so.50 This report acted as one more objection to the Women Airforce Service Pilots, and even though the Army Appropriations Bill for 1945 had passed through Congress, giving the WASP program six million dollars for funding, the House voted the Costello Bill down by nineteen votes on June 21, 1944.51 All of the opposition to the Costello Bill crippled its chances of passing even though earlier militarization bills for other women’s organizations, such as the WAC and Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Services (WAVES), had already passed through Congress.52 This bill was the WASPs last hope for militarization, although they did 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 Verges, 188. Ibid. Schrader, 144–45. Ibid., 144. Ibid., 142. Committee on the Civil Service, Concerning Inquires Made of Certain Proposals for the Expansion and Change in Civil Service Status of the WASPs, 78th Cong., 2d sess., 1944, H. Rep. 1600, 1. Ibid., 13. Cochran to Commanding General, B2, 1 August 1944, WASP Virtual Collection. Schrader, 140. 44 not realize it at the time, because within six months, female pilots no longer flew for the military. The Costello Bill started the ball rolling toward deactivation of the Women Airforce Service Pilots, and its failure to pass in the House prompted Cochran to write a report, which pushed the ball along even faster. The debate in the House and the Ramspeck Report showed so much opposition to the WASP training program that the AAF decided to cancel it on June 26, just days after the bill’s failure, even though the Appropriations Committee had just put aside funds to continue it.53 Part of the reason for canceling the training program was that the war was going well and the AAF did not need many new pilots.54 The WASPs already enrolled at Avenger Field finished their training and graduated, but those who had just arrived had to turn around and go back home.55 If the AAF had decided to continue the training program in June, it would have incited more public opinion against them, which they did not want. The Costello Bill had stirred up the public, press, and Congress so much that the chances of getting another WASP militarization bill passed in the near future seemed unlikely. On August 1, 1944, Cochran wrote a report, which she sent to Arnold and the press, to push for WASP militarization even though the Costello Bill had recently failed. One author suggests that she did this to try to get some action on the Costello Bill that still sat in the Senate.56 Cochran’s report gives a history of the WASPs and highlights their accomplishments. The goal of the report was to inform everyone about the facts of the program and show why Congress should militarize the WASPs.57 Because of problems that arose from female pilots not being militarized, Cochran ended the report with what was essentially an ultimatum, stating, “Serious considerations should be given to inactivation of 53 54 55 56 57 Cochran to Commanding General, D8, 1 August 1944, WASP Virtual Collection. Schrader, 140. Ibid., 16. Verges, 200. Cochran to Commanding General, 1 August 1944, WASP Virtual Collection. 45 the WASP program if militarization is not soon authorized.”58 If the Costello Bill had passed the House, Cochran would not have felt that it was necessary to send out this report. The press treated the report like an ultimatum and, apparently, so did the Army Air Force because later that month they started making plans for the WASP’s deactivation.59 In October, Arnold sent Cochran a letter to tell her that it was time to plan for WASP deactivation, and later that month, they both sent a letter to all of the WASPs explaining that the Army Air Force would deactivate the program on December 20, 1944.60 Arnold said the AAF did not need them anymore, and if they were to stay, they would replace men, not release them as they had been doing.61 The announcement shocked the female pilots because they had not seen it coming, and as far as they could tell, the Army Air Force still needed them because they were constantly busy flying for the AAF.62 Upon deactivation, some of the WASPs even offered to continue flying for one dollar a year, but Arnold turned them down.63 The women were crushed to know that they had to leave before the war was over. In the end, the AAF deactivated the WASPs without ever finding a successful way to militarize them, which would have given them benefits and recognized them as veterans of the Air Force. 58 59 60 61 62 63 Ibid., J1d. Schrader, 16–17. On the letter to Cochran, see H. H. Arnold to Director of Women Pilots, “Deactivation of WASP,” 1 October 1944, Online Documents, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library. On the letter to the WASPs, see Jacqueline Cochran to Members of the 43-W-3 Class, 12 October 1944, Online Documents, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library. Arnold to Director of Women Pilots, 1 October 1944. Before the AAF actually deactivated the WASP, the Ferrying Division tried to keep the WASPs they already had under their employment, but Arnold denied their request. Verges, 211–12 and Brigadier General Nowland to Commanding General, Air Transport Command, secret memorandum, 1 November 1944, http://wingsacrossamerica.us/records_all/press_archive/nowland.pdf. When some of the WASPs left to go home on December 20, planes still sat on the ground waiting to be delivered, showing that the AAF did still need them as the Ferrying Division had said. Fly Girls, produced by Laurel Ladevich, 56 minutes, PBS Video, 2006, DVD and Nathan, 78. Schrader, 149. 46 Nancy Love and Jackie Cochran’s wish to have the WASP and its predecessors militarized never came true because of the opposition it faced when they later tried, not only from people in the Army Air Force but also from the public. Militarizing under the WAC, giving out direct commissions, and passing the Costello Bill were all options Love, Cochran, and Arnold attempted, but because of resistance to them, they were never successful. With the failure of the Costello Bill came the termination of the training program and, soon after that, the deactivation of the whole WASP program. The WASPs did not want to quit flying for the military because they loved to fly and most of them knew they would never have the chance to fly military aircraft again. After deactivation, the women went back home, and people soon forgot they ever existed, even the press, who in 1977 said that the new women recruits for the Air Force were the first women to ever fly military aircraft for the United States.64 Around the same time in 1977, the WASPs again began the fight in Congress to gain military recognition. Thirty-three years after the Army Air Force deactivated them and Congress denied them militarization, the women became veterans with the passage of the GI Bill Improvement Act of 1977 on November 3.65 These women flew military aircraft in World War II, proving that women were capable of flying them, and they thoroughly enjoyed the time they spent training and doing what they loved: flying. In the end, the WASPs got the recognition they deserved and earned their place in history. 64 65 Verges, 146. Ibid., 147. 47