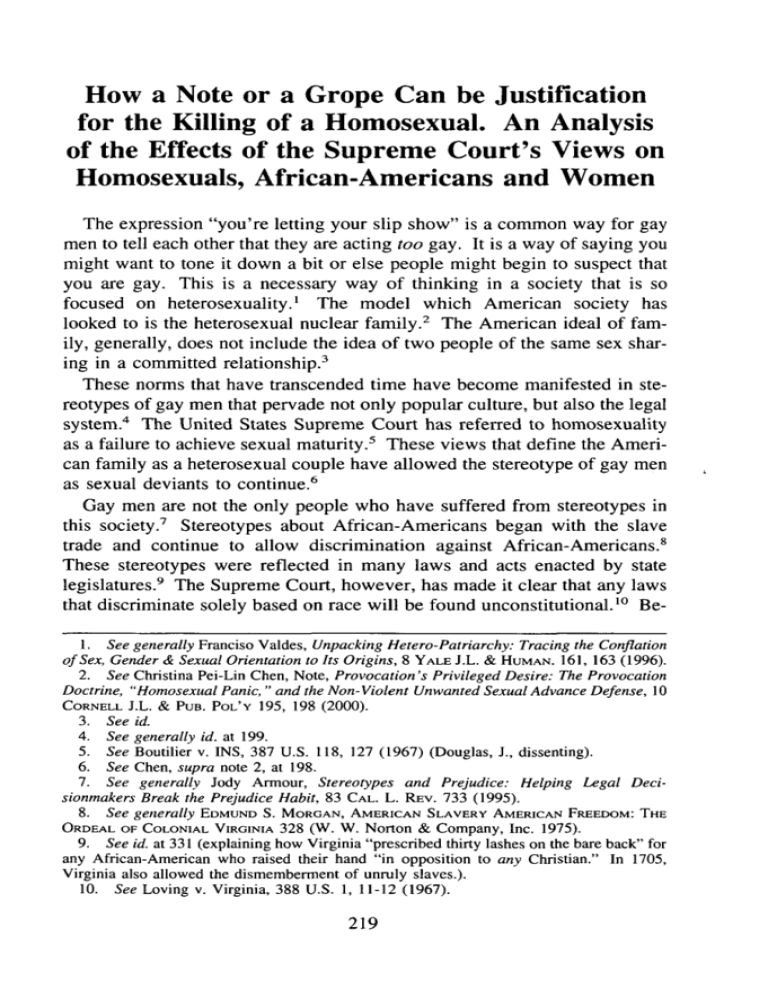

How a Note or a Grope Can be Justification

for the Killing of a Homosexual. An Analysis

of the Effects of the Supreme Court's Views on

Homosexuals, African-Americans and Women

The expression "you're letting your slip show" is a common way for gay

men to tell each other that they are acting too gay. It is a way of saying you

might want to tone it down a bit or else people might begin to suspect that

you are gay. This is a necessary way of thinking in a society that is so

focused on heterosexuality.' The model which American society has

looked to is the heterosexual nuclear family.2 The American ideal of family, generally, does not include the idea of two people of the same sex sharing in a committed relationship.'

These norms that have transcended time have become manifested in stereotypes of gay men that pervade not only popular culture, but also the legal

system.4 The United States Supreme Court has referred to homosexuality

as a failure to achieve sexual maturity.5 These views that define the American family as a heterosexual couple have allowed the stereotype of gay men

as sexual deviants to continue.6

Gay men are not the only people who have suffered from stereotypes in

this society. 7 Stereotypes about African-Americans began with the slave

trade and continue to allow discrimination against African-Americans.8

These stereotypes were reflected in many laws and acts enacted by state

legislatures. 9 The Supreme Court, however, has made it clear that any laws

that discriminate solely based on race will be found unconstitutional.° Be1. See generally Franciso Valdes, Unpacking Hetero-Patriarchy:Tracingthe Conflation

of Sex, Gender & Sexual Orientation to Its Origins, 8 YALE J.L. & HUMAN. 161, 163 (1996).

2. See Christina Pei-Lin Chen, Note, Provocation'sPrivilegedDesire: The Provocation

Doctrine, "Homosexual Panic," and the Non-Violent Unwanted Sexual Advance Defense, 10

CORNELL J.L. & PUB. POL'Y 195, 198 (2000).

3. See id.

4.

See generally id. at 199.

5.

See Boutilier v. INS, 387 U.S. 118, 127 (1967) (Douglas, J., dissenting).

6.

See Chen, supra note 2, at 198.

7. See generally Jody Armour, Stereotypes and Prejudice: Helping Legal Decisionmakers Break the Prejudice Habit, 83 CAL. L. REV. 733 (1995).

8. See generally EDMUND S. MORGAN, AMERICAN SLAVERY AMERICAN FREEDOM: THE

ORDEAL OF COLONIAL VmGINIA 328 (W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. 1975).

9. See id. at 331 (explaining how Virginia "prescribed thirty lashes on the bare back" for

any African-American who raised their hand "in opposition to any Christian." In 1705,

Virginia also allowed the dismemberment of unruly slaves.).

10. See Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1, 11-12 (1967).

CRIMINAL AND CIVIL CONFINEMENT

[Vol. 29:219

cause of that decision, the legal system has begun to adapt to society's

changing views of African-Americans."

Women have also been discriminated against strictly because of their

gender. 2 However, as the women's movement gained momentum, women

gained many of the constitutional rights that had always been guaranteed to

men. 3 The Supreme Court stated that in many situations women had not

been treated any differently than African-Americans had before the end of

slavery.' 4 With this change in society's views of women, states also began

to adopt statutes to put women on a more equal footing with men. 5

In contrast to their changing views on African-Americans and women,

the Supreme Court, through decisions like Bowers v. Hardwick'6 and Boutilier v. INS,' 7 has set the standard for the views of homosexuals in today's

society.' 8 By continuing to label homosexuality as being against JudeaoChristian morals, the Court has set the stage for discrimination against

homosexuals in society and in the court system.' 9

The murder of Matthew Shepard provides an example of how two heterosexual men tried to justify the brutal beating of a gay man, by the alleged

sexual advance made by Mr. Shepard toward one of the men.2" This advance, which by the heterosexual man's own account, amounted to Mr.

Shepard grabbing the man's groin area and blowing in his ear.2 ' The defense attempted to say that this advance somehow justified tying Mr. Shepard to a fence, beating him with a pistol and leaving him to die.2 The

murder of Scott Amedure provides another example of how a voluntary

appearance on a talk show, combined with a "sexually suggestive note" left

on a front door, can be manipulated by the defense into a justification for

shooting a homosexual to death in the doorway of his home.2 3

This Comment will contrast the Supreme Court's views on homosexuals,

African-Americans and women. This Comment will analyze how the court

11.

12.

See generally id.

See generally Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U.S. 677 (1973).

13.

14.

15.

See id. at 687.

See id. at 685.

See id. at 687.

16.

17.

18.

478 U.S. 186 (1986).

387 U.S. 118 (1967).

See generally Bowers v. Hardwick, 478 U.S. 186 (1986).

See also Boutilier, 287

U.S. at 127. In Bowers, the Court labeled homosexuality as being against Judeao-Christian

morals, and in Boutilier, the Court labeled heterosexuality as sexual maturity.

19.

See Bowers, 478 U.S. at 196.

20.

See Chen, supra note 2, at 196.

21.

See Bryan Robinson, PathologistDetails Shepard's Fatal Injuries, CourtTV Online,

Oct. 27, 1999, at http://www.courttv.com/trials/McKinney/102699 ctvhtml (last visited Jan.

15, 2003).

22.

See id.

23.

See People v. Schmitz, 581 N.W.2d 766, 768 (1998).

Summer, 2003]

SUPREME COURT AND HOMOSEXUALITY

221

system has adapted to society's changing views of African-Americans and

women by providing heightened sentences for crimes against AfricanAmericans, and by protecting rape victims through rape shield laws. However, the tone set by the Supreme Court continues to allow excuses for

violence against homosexuals.

Part One will examine the history of homosexuality. It will illustrate

how the Supreme Court has created a moral view that condemns homosexuals. 24 This moral condemnation is evidenced through the Gay Panic Defense, which provides a justification for violence against homosexuals.2 5

This defense will be illustrated through an analysis of the trials surrounding

the deaths of Matthew Shepard and Scott Amedure, and how the victims'

character as gay men became the focus of the defense teams.26

Part Two of this Comment will look at the historical perspectives of slavery and stereotypes surrounding African-Americans. It will show how the

Civil Rights Movement changed how people viewed African-Americans,

and how the court system adapted to those changing societal views. An

examination of the dragging death of James Byrd, Jr. will show how the

prosecution of a hate crime against an African-American focused on the

person who committed the act and not on the victim. Part Two will also

address how hate crime legislation has provided for heightened sentencing

requirements for perpetrators of hate crimes against African-Americans.

Part Three will look at the historical perspective of women and how they

have gained some equal footing with men. As society's views of women

have changed, the court system has adapted to those changing views. Women were given the right to vote, the right to hold office, and the right to

privacy to make decisions about their own bodies.2 7 Part of this privacy

right regarding a woman's body is reflected in the vast changes in rape

law.2 8 These changes are most evident in the modification of rape law and

rape shield statutes that are designed to protect the victim of rape from

having her past sexual history used against her in court.29 This changing

24.

See generally Bowers, 478 U.S. 186 (explaining how homosexuality is against

Judeao-Christian morals).

25.

See Kara S. Suffredini, Note, Pride and Prejudice:The Homosexual Panic Defense,

21 B.C. THIRD WORLD L.J. 279, 279 (2001).

26. See Chen, supra note 2, at 196. See generally Suffredini, supra note 25, at 279.

27. See Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, 157 (1973); see also Frontiero,411 U.S. at 685.

28. See Sakthi Murthy, Comment, Rejecting UnreasonableSexual Expectations: Limits

on Using a Rape Victim's Sexual History to Show the Defendant's Mistaken Belief in Con-

sent, 79 CAL. L. REV. 541, 543 (1991) (explaining how earlier rape law placed the victim on

trial and how public pressure provided for changes in rape law to protect the victim during

cross-examination).

29. See id.

CRIMINAL AND CIVIL CONFINEMENT

[Vol. 29:219

view will be illustrated through the State in Interest of M.T.S., a New Jersey

3

rape trial, and the rape and murder of Barbara Williams. "

Part Four of this Comment will analyze the Supreme Court's opportunity

to reexamine the rights of homosexuals. In Lawrence v. State3 two homosexual men were convicted of violating the Texas statute that makes it ille32

In facts very

gal for two people of the same sex to engage in sodomy.

33

similar to the landmark case of Bowers v. Hardwick, Lawrence offered the

Supreme Court an opportunity to reassess society's views of homosexuality

and the privacy rights of homosexuals in their bedroom.

I.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES OF HOMOSEXUALITY AND THE

DEVELOPMENT OF THE HOMOSEXUAL PANIC DEFENSE

Modem views of homosexuality and its role in society began with the

ancient Greeks.34 In Greek culture, male same-sex relationships "were

deemed the ideal physical and spiritual venue for the pursuit of love,

beauty, friendship, and camaraderie among those born to lead."3 5 Homosex36

Eventually,

ual relationships were not only accepted, but celebrated.

37

Greece came into the Roman Empire. With the rise of the Roman Empire

came the development of Christianity.3 8 With the rise of Christianity, women continued in their passive, submissive roles, and same-sex partnerships

began to be considered immoral.39 These themes began to prevail through

the ages as Christianity spread and many religions began to condemn

homosexuality. 4"

From this heterosexual society, cultural stereotypes began to develop into

ideas that set the stage for discrimination against homosexuals. 4 ' A sexual

protocol developed that men would pursue women and women would be

pursued by men.42 While women were relegated to be the ones pursued,

society set norms whereby men were not to be placed in the role of being

pursued.4 3 When one man makes a sexual advance toward another man, this

30.

See generally State in Interest of M.T.S., 609 A.2d 1266 (N.J. 1992).

31.

41 S.W.3d 349 (2001).

32.

See id. at 350.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

See generally Bowers, 478 U.S. 186; Lawrence, 41 S.W.3d 349.

See Valdes, supra note 1, at 162.

Id. at 184.

See id. at 186.

See id. at 199.

See id.

See Valdes, supra note 1, at 201.

See generally id. at 202.

See Chen, supra note 2, at 198.

42.

See generally BRYAN

43.

STRONG ET AL., HUMAN SEXUALITY DIVERSITY IN CONTEMPO-

130, 131-32 (3d Ed. 1999).

See Suffredini, supra note 25, at 284.

RARY AMERICA,

Summer, 2003]

SUPREME COURT AND HOMOSEXUALITY

223

goes against his view of what society expects from men. 44 In order to reestablish himself as the heterosexual, dominant male, he has to reaffirm his

dominant position by acting aggressively toward the gay male.4 5

By the 1920s, with heterosexual bias firmly in place in society, the stage

was set for the court system to adopt biases against homosexuals. The homosexual panic defense first appeared in the 1920s, as defined by psychiatrist, Edward Kempf.4 6 His definition of a "homosexual panic" was an

"anxiety attack [that] was 'due to the pressure of uncontrollable perverse

sexual cravings."' 4 7 Other psychologists later defined homosexual panic in

terms of latent homosexual desires that were provoked or awakened by a

homosexual advance.4 8 In the 1970s, the Psychiatric Dictionary defined ho-

mosexual panic as "'an acute, severe episode of anxiety related to the fear

... that the subject is about to be attacked sexually by another person of the

same sex, or that he is thought to be a homosexual by fellow-workers.' "9

The fear of being labeled a homosexual came from the medical definition

and psychological classification of the word homosexual at the time.5 ° Prior

to 1973, homosexuality was listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

of Mental Disorders as a psychological disorder.5" It was this view of homosexuality as a psychological disorder that led to the establishment of the

defense of a homosexual panic.5 2 The basic idea was that a man could be so

threatened by his own latent homosexual desires, that when confronted by a

man who made a sexual advance he would lose control and commit a violent act.53 In 1973, when the Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its list of psychological disorders, the homosexual panic defense

lost its medical background.5 4 However, the defense began to be used as a

way to mitigate charges from first-degree murder to manslaughter.55

44. See id.

45. See id.

46. See Robert G. Bagnall et al., Comment, Burdens on Gay Litigants and Bias in the

Court System: Homosexual Panic, Child Custody, and Anonymous Parties, 19 HARv. C.R.C.L. L. Rav. 497, 499 (1984) [hereinafter Burdens on Gay Litigants].

47. Id. (alteration in original).

48. See id. at 499-500.

49. Id. at 500 (citing LELAND E. HINSIE & ROBERT J. CAMPBELL, PSYCHIATRIC DicIONARY, 348 (4th ed. 1970)).

50. See Chen, supra note 2, at 200.

51. See id. at 202.

52. See id.

53. See id. at 200-01.

54. See id. at 202.

55. See Chen, supra note 2, at 203.

CRIMINAL AND CIVIL CONFINEMENT

[Vol. 29:219

The Supreme Court's Views

A.

1. Boutilier v. INS

In 1967, the Supreme Court was faced with an appeal of a deportation

orderagainst a Canadian. 6 The Canadian, Mr. Boutilier, had been ordered

deported under the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952." 7 This Act has

a clause that denies people with "psychopathic personality" entry into the

United States.5 8 Between 1955 and 1959, Mr. Boutilier had made several

trips between Canada and the United States.5 9 In 1963, Mr. Boutilier applied for citizenship, at which time he disclosed that he had once been arrested for sodomy.6" He explained that the charges had been reduced to

assault, and later dismissed because of default by the other party. 6 ' However, Mr. Boutilier's citizenship application was denied and he was ordered

deported to Canada.62 In reaching its decision to deport Mr. Boutilier, the

Supreme Court relied on the complete sexual history of Mr. Boutilier that

the lower court had required.6 3 Included in that sexual history was not only

how often Mr. Boutilier had engaged in homosexual sex, but also whether

or not he was the "active" or "passive" participant in the sex act.64

The Supreme Court ultimately affirmed the decision to deport Mr. Boutilier.6 5 In making its decision, the Court further relied on a report from the

Public Health Service, which stated that the physicians concluded that Mr.

Boutilier "'was afflicted with a class A condition, namely, psychopathic

personality, sexual deviate.' ,66 The Court also reviewed the legislative history of the Immigration and Nationality Act and concluded that the legislature had intended to include homosexuals under the phrase "psychopathic

personality" and thereby deny homosexuals the right to immigrate to the

United States.67 Justices Douglas and Fortas' dissent in Boutilier suggested

that "[t]he term 'psychopathic personality' is a treacherous one like

'communist.' ,61

The dissent argued that Mr. Boutilier's occasional homosexual activities

did not constitute an affliction of a psychopathic personality. 69 Because

56.

57.

58.

59.

See

See

See

See

Boutilier, 387 U.S. at 118.

id.

id. at 119.

id.

60.

61.

62.

63.

See

See

See

See

id.

Boutilier, 387 U.S. at 119.

id. at 120.

id. at 119.

64.

See id.

65.

66.

67.

See id. at 125.

Boutilier, 387 U.S. at 120.

See id. at 119.

68.

69.

Id. at 125 (Douglas & Fortas, JJ., dissenting).

See id. at 133-34.

Summer, 2003]

SUPREME COURT AND HOMOSEXUALITY

225

Mr. Boutilier experienced not only homosexual relationships, but also heterosexual relationships and periods of abstinence, the dissent felt that deportation would be too harsh a penalty.7v The dissent reasoned that Mr.

Boutilier's occasional homosexual acts were not enough to say that he was

"afflicted" with a psychopathic disorder. 7 The dissent relied on a psychologist who testified that "'[a]fflicted' means a way of life, an accustomed

pattern of conduct." 2 By making such a statement, the dissent left open the

idea that had Mr. Boutilier been engaged in long-term homosexual behavior, the dissent would have agreed with the majority that Mr. Boutilier was

afflicted with a psychopathic disorder because of his homosexuality. 3

2.

Bowers v. Hardwick

In the early 1980s, the Supreme Court once again addressed issues surrounding homosexuals. It had been more than ten years since the Boutilier

decision, and within that time, the term "homosexual" had been removed

from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as a mental

disease.7 4 However, the Supreme Court continued to use homosexual stereotypes to persuade its decision in Bowers v. Hardwick. 5 Bowers dealt

with a Georgia statute that outlawed sodomy.7 6 The ban on sodomy was

not exclusive to homosexuals, and the act of sodomy included both oral and

anal sex.77 Mr. Hardwick was charged with violating this statute with another consenting adult male in the privacy of his own bedroom.7 8

In an interview in 1988, Mr. Hardwick explained the events that led up to

79

the Supreme Court's monumental decision in Bowers v. Hardwick.

It was

8°

the early 1980s in Atlanta, Georgia.

A known gay bar was completing

some renovations, and Mr. Hardwick was helping the owners with the renovations. 8 1 Early in the morning, Mr. Hardwick left the club, and while

standing outside the club, he threw a beer bottle into a trashcan.8 2 A police

car followed Mr. Hardwick and finally stopped him, and the officer placed

70.

71.

See id.

See Bowers, 387 U.S. at 133.

72.

73.

74.

75.

76.

77.

78.

Id. (Douglas, J., dissenting).

See generally id.

See Chen, supra note 2, at 202.

See generally Bowers, 478 U.S. 186.

See id. at 186.

See id. at 188 n.I.

See id. at 188.

79. See WILLIAM B. RUBENSTEIN, SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND THE LAW 217 (2d 1997)

(containing an excerpt from PETER IRONS, What Are You Doing in My Bedroom?, in THE

COURAGE OF THEIR CONVICTIONS

80.

81.

82.

See id. at 218.

See id.

See id.

392 (1988)).

CRIMINAL AND CIVIL CONFINEMENT

[Vol. 29:219

Mr. Hardwick in the back of the police car.83 After some time riding

around, the police officer gave Mr. Hardwick a ticket for public consumption of alcohol.8 4 A heated exchange occurred between Mr. Hardwick and

the officer, in which Mr. Hardwick accused the officer of harassing him

because he was leaving a gay bar.85 When the officer issued the ticket there

was a discrepancy between the date set for the hearing and the day of the

week written at the top of the ticket.86 Because of the discrepancy, Mr.

Hardwick went to the hearing on the wrong day, and the officer had a warrant issued for Mr. Hardwick's arrest.87 When Mr. Hardwick realized that

the warrant had been issued, he had it cleared up with the court, and the

warrant was revoked. 88

A few weeks later, the same officer, carrying the original warrant, went

to Mr. Hardwick's apartment early one morning.89 The front door was

open and the officer walked into the front room of the house where he saw

Mr. Hardwick's roommate asleep on the couch.9" The officer went to the

doorway of Mr. Hardwick's bedroom and observed Mr. Hardwick and a

friend engaging in consensual sexual acts.9 1 After standing in the doorway

and watching, the police officer arrested Mr. Hardwick and used the warrant to take him to jail.9" After he got to jail, the police officer made sure

that all the other people in the jail cell were aware that Mr. Hardwick was

arrested for homosexual conduct.9 3 The officer further explained, for everyone to hear, that Mr. Hardwick was "in there for 'cocksucking' and that

[Mr. Bowers] should be able to get what [he] was looking for."94

Mr. Hardwick eventually was able to clear up the issue behind the warrant, and after consulting some Atlanta lawyers who had been trying to fight

Georgia's sodomy laws, decided to sue the State of Georgia over these

laws.95 Mr. Hardwick eventually brought suit in federal district court, chal96

lenging the constitutionality of the statute.

What is rarely mentioned is that at the time Mr. Hardwick brought the

suit in federal court, a heterosexual couple were also plaintiffs in the ac83.

See id.

84.

See

RUBENSTEIN,

85.

86.

87.

88.

See

See

See

See

id.

id. at 218-19.

id. at 219.

id.

89.

See

RUBENSTEIN,

90.

91.

92.

93.

See

See

See

See

id. at 219-20.

id. at 220.

id.

id.

94.

See

RUBENSTEIN,

95.

96.

See id.

See id. at 221-22.

supra note 79, at 218.

supra note 79, at 219.

supra note 79, at 220.

Summer, 2003]

SUPREME COURT AND HOMOSEXUALITY

227

tion.97 They claimed that they too wanted to engage in the acts prohibited

by Georgia's statute in the privacy of their home.9 8 The district court held

that "because they had neither sustained, nor were in immediate danger of

sustaining, any direct injury from the enforcement of the statute, they did

not have proper standing to maintain the action."9 9 The court of appeals

affirmed the district court's decision to not allow the heterosexual couple to

be considered plaintiffs in the action."

The statute in question did not specify whether it applied to homosexuals

or heterosexuals.l"l The language of the statute clearly states: "'[a] person

commits the offense of sodomy when he performs or submits to any sexual

act involving the sex organs of one person and the mouth or anus of another

... [],

,1,

However, when the Supreme Court addressed the constitution-

ality of the statute the Court primarily focused on homosexuals rights to

engage in sodomy. 0 3 The Court stated: "The issue presented is whether

the Federal Constitution confers a fundamental right upon homosexuals to

engage in sodomy and hence invalidates the laws of the many States that

still make such conduct illegal and have done so for a very long time."' 4

Before the Supreme Court heard the Bowers case, the court of appeals

had determined that the right of privacy extended a fundamental right to

homosexuals to engage in sodomy.'0 5 However, the Supreme Court stated

that none of the decisions in the right to privacy cases extended the right of

homosexuals to engage in sodomy.'0 6 The Court based its decision on their

traditional view of family, and the notion that relationships between homosexuals did not involve the traditional views of family. 107 "No connection

between family, marriage, or procreation on the one hand and homosexual

activity on the other has been demonstrated, either by the Court of Appeals

or by respondent."' 0 8

The Supreme Court looked to the historical context of anti-sodomy

laws." ° The Court indicated that "[s]odomy was a criminal offense at common law and was forbidden by the laws of the original 13 States when they

ratified the Bill of Rights.'' 1 The Court concluded that the right of homo97.

98.

99.

See id.

See Bowers, 478 U.S. at 188 n.2.

Id.

100.

101.

See id.

See id. at 188 n.L

102.

Id. (alteration in original).

103.

See Bowers, 478 U.S. at 190.

104.

105.

106.

Id.

See id.

See id. at 190-91.

107.

108.

See id. at 191.

Bowers, 478 U.S. at 191.

109.

See id. at 192.

110.

Id.

CRIMINAL AND CIVIL CONFINEMENT

[Vol. 29:219

sexuals to engage in sodomy was not "'deeply rooted in this Nation's history and tradition.' "'

I

In making its decision, the Court addressed its decision in Stanley v.

Georgia,"12 which dealt with a person's right to possess obscene material in

the privacy of one's home." 3 The Court reasoned that even though Stanley

dealt with acts committed in the privacy of one's own home, they were not

ready to extend this privacy right to homosexuals.' 14 "[I]t would be difficult

. . .

to limit the claimed right to homosexual conduct while leaving

exposed to prosecution adultery, incest, and other sexual crimes even

though they are committed in the home. We are unwilling to start down

that road."11' 5 Chief Justice Burger, in a concurring opinion, stated that

"[c]ondemnation of... [homosexual] practices

is firmly rooted in Judeao' 16

Christian moral and ethical standards."

The dissent strongly disagreed with the focus of the majority on the acts

of homosexuals.' 7 Justice Blackmun, Justice Brennan, Justice Marshall

and Justice Stevens wrote "[t]his case is no more about 'a fundamental right

to engage in homosexual sodomy,' as the Court purports to declare.., than

Stanley v. Georgia .. .was about a fundamental right to watch obscene

movies."'8 The dissenting justices concluded that "this case was about

'the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized

men,' namely, 'the right to be let alone.""' 9 The dissent went on to say

that just because Judeao-Christian ideals condemned homosexuality, that

gave no right to the Court to force those beliefs on the American public as a

20

whole. 1

In decisions like Boutilier and Bowers, the Supreme Court set the tone

for the continued discrimination against homosexuals and the continuation

of the homosexual panic defense. 21 In the following cases, homosexual

men were killed by heterosexual men, and the homosexual panic defense

allowed the possibility for the manipulation of any prejudices jury members

22

may have had.'

111. Id. at 194.

112. 394 U.S. 557 (1969).

113. See Bowers, 478 U.S. at 195 (referring to Stanley v. Georgia, 394 U.S. 557 (1969)).

114. See id. at 195.

115. Id. at 195-96.

116. Id. at 196 (Burger, C.J., concurring).

117. See id. at 199.

118. Bowers, 478 U.S. at 199 (citations omitted) (Blackmun, J.,

dissenting).

119. Id. (quoting Olmstead v. U.S., 277 U.S. 438, 478 (1928)) (Blackmun, J.,

dissenting).

120.

121.

122.

See discussion supra Part I.A.

See discussion supra Part I.A.

See generally discussion supra Part I.A.

Summer, 2003]

B.

SUPREME COURT AND HOMOSEXUALITY

229

The Homosexual Panic Defense

1. The Murder of Matthew Shepard

In October of 1998, two cyclists on a Wyoming road came across what

they thought was a scarecrow tied to a fence.' 2 3 What they found was the

badly beaten body of Matthew Shepard.' 24 The 21-year-old body of Matthew Shepard had been beaten with the butt of a pistol and burned.1 25 After

four days of lying in a26hospital, Matthew Shepard died from the injuries

suffered in the attack.'

Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson were arrested in connection

with the attack.127 The men stated that they had met Mr. Shepard at a local

bar. 2 8 They had apparently told Mr. Shepard that they were gay and all

three men got into the defendant, Mr. McKinney's, truck and drove out into

the Wyoming countryside.' 29 Once in the truck, the men told Mr. Shepard,

"'We're not gay - you've been jacked.'"130 They then drove the 5'2", 105

pound Mr. Shepard out to a deserted roadside. 3 ' Mr. McKinney testified

that once they were in the truck, Mr. Shepard made a sexual advance toward the men.' 3 2 They then pulled off to the side of the road and ordered

McKinney began beating Mr. Shepard

Mr. Shepard out of the car. 13 3 Mr.

34

while Mr. Henderson watched. 1

Prosecutor Calvin Rerucha said there was abundant evidence to formally

charge Mr. McKinney. 1 35 In his opening statements at a preliminary hearing, Mr. Rerucha described the bloody scene. 136 He indicated that after the

beating, Mr. Shepard remained in the cold Wyoming night for eighteen

hours before being found. 137 The only place on his body that was not cov123.

Statutes:

124.

125.

126.

See Scott D. McCoy, Note, The Homosexual-Advance Defense and Hate Crimes

Their Interaction and Conflict, 22 CARDOZO L. REV. 629 (2001).

See id.

See id.

See id. at 630.

127. See Kathryn Rubenstein, Wyoming v. Aaron J. McKinney PreliminaryEvidence

Heard in Wyoming Beating, CourtTV Online, Nov. 19, 1998, at http://www.courttv.com/

trials/gaybashing/mckinney-prelim.htm (last visited Jan. 15, 2002) [hereinafter Wyoming v.

Aaron J.

128.

129.

130.

131.

McKinney].

See id.

See id.

Id.

See id.

132. See Robinson, supra note 21, at http://www.courttv.com/trials/mckinney/10

ctv.html.

133.

2 69 9

-

See Wyoming v. Aaron J. McKinney, supra note 127, at www.courttv.com/trials/

gaybashing/mckinney-prelim.html.

134.

135.

See id.

See id.

136.

See id.

137.

See id.

CRIMINAL AND CIVIL CONFINEMENT

[Vol. 29:219

ered in blood was on his face where tears had washed away the blood. 138

Mr. Shepard must have known what was coming that night, because Mr.

139

Shepard had been beaten twice before for being an outwardly gay man.

The big break in the connection between Mr. Henderson and Mr. McKinney came from Mr. McKinney's girlfriend, Kristen Price.' 0 Ms. Price told

the officers that she had helped dispose of the bloody clothes when Mr.

McKinney came home that evening. 4 ' She further explained to the officers

that "'McKinney struck him while Henderson laughed.' 1 4 2 Mr. Henderson then tied Mr. Shepard up, and Mr. Shepard begged for his life, while

both men beat him until he was unconscious. 143 In a recorded interview

with Mr. McKinney, he stated that they left Mr. Shepard for dead tied to the

fence. 144

The trial against Mr. Henderson began in March of 1999.145 His defense

was based on his claims that "he did not participate in Shepard's beating,

and that the murder was not premeditated."' 146 Because the penalty could

have been death, Mr. Henderson decided to plead guilty to Mr. Shepard's

kidnapping and murder.' 4 7 In exchange for the guilty plea, Mr. Henderson

14 8

was to receive two consecutive life terms.

The trial against Mr. McKinney began in October of 1999.149 The defense attorneys planned to plead the "gay 'panic' defense."' 50 In his opening argument, public defender Jason Tangeman admitted that Mr.

McKinney had killed Matthew Shepard. 5 ' Mr. Tangeman stated that Mr.

McKinney's motive was homosexual panic. 152 Mr. Tangeman explained

that on the night of the beating, Mr. Shepard was riding in the pick-up truck

with Mr. McKinney and Mr. Henderson.'

Mr. Tangeman told the jury

138.

See Wyoming v. Aaron J. McKinney, supra note 127, at www.courttv.com/trials/

gaybashing/mckinney-prelim.html.

139.

140.

141.

See id.

See id.

See id.

142.

Id.

143.

See Wyoming v. Aaron J. McKinney, supra note 127, at www.courttv.com/trials/

gaybashing/mckinney-prelim.html.

144. See id.

145. Kristen M. Jasket, Note, Racists, Skinheads and Gay-Bashers Beware: Congress

Joins the Battle Against Hate Crimes By Proposing the Hate Crimes PreventionAct of 1999,

24

SETON HALL LEGIS.

146.

Id.

147.

See id.

J. 509, 515 (2000).

148. See id.

149. Id. at 515-16.

150. See Jasket, supra note 145, at 516.

151. See Robinson, supra note 21, at http://www.courttv.com/trials/mckinney/

102699_ctv.html.

152.

153.

See id.

See id.

Summer, 2003]

SUPREME COURT AND HOMOSEXUALITY

231

that "Shepard made an unwanted advance towards McKinney by putting his

hand on the defendant's groin and sticking his tongue in McKinney's

ear.' 154 Mr. Tangeman said that this alleged homosexual advance which

brought back traumatic childhood memories for Mr. McKinney. 5 5 Allegedly, Mr. McKinney had been the subject of homosexual abuse by a neighborhood bully. 56 Mr. Shepard's advance, according to Mr. Tangeman,

triggered a rage during which Mr. McKinney blacked out.157 It was during

this alleged five-minute blackout that Mr. McKinney apparently fastened

Mr. Shepard to a wooden fence and whipped him with a pistol.' 5 8

The judge in the case eventually denied the defense's ability to use the

homosexual panic defense.' 5 9 Even though the defense had never referred

to their defense as a homosexual panic defense, the judge determined that

the defense's "strategy was a form of temporary insanity or diminished caBecause Wyoming did not allow either defense, the judge

pacity. '

barred the defense from employing this strategy.16 1 However, the judge

stated that, had the case been decided by the jury and continued to the sentencing phase, the elements of the homosexual panic defense could have

been used.16 2 "Ultimately, Shepard's parents interceded and asked that McKinney be sentenced to life in prison without parole rather than face the

death penalty."' 63

The Matthew Shepard case demonstrates how stereotypes of gay men

have enabled hate crimes to be committed against gay men.'" Matthew

65

Shepard did not come on to these two men in some darkened back alley.'

It appears more likely that these men basically set him up to trick him into

going out into the deserted Wyoming countryside. 66 They were the ones

that initially indicated to Mr. Shepard that they were gay. 1 67 The defense

team for the perpetrators, however, tried to establish that they were somehow justified in their reaction to Matthew Shepard.' 68 The basis for this

154.

155.

156.

Id.

See id.

See Robinson,

supra note

21,

at http://www.courttv.com/trials/mckinney/

102699_ctv.html.

157. See id.

158.

See id.

159.

See Text of the "Gay Panic" Defense Ruling in the Matthew Shepard Murder Trial,

CourtTV Online, Nov. 1, 1999, at http://www.courttv.com/trials/mckinney/gay-panic-ruling

_ctv.html (last visited Jan. 15, 2003) [hereinafter "Gay Panic" Defense].

160. Id.

161. See id.

162. See id.

163.

Jasket, supra note 145, at 516.

164.

165.

See generally id.

See generally id.

166.

See generally id.

167.

168.

See generally id.

See generally Jasket, supra note 145.

CRIMINAL AND CIVIL CONFINEMENT

[Vol. 29:219

justification is rooted in how homosexuals are perceived in modem society. 169 Even the attempted use of a homosexual panic defense demonstrates

how the potential exists for the court system to provide an excuse for violence against homosexuals. 7 ° Had the trial continued to the sentencing

phase, Matthew Shepard's identity as a gay man could have been

exploited

17

possible.

sentence

lowest

the

obtain

to

order

by the defense in

2.

The Murder of Scott Amedure

In 1995, Jonathan Schmitz appeared on The Jenny Jones Show, where the

identity of a person who had a crush on Mr. Schmitz was to be announced.1 72 As the cameras were rolling, a man, Scott Amedure, emerged

and announced that he was the person who had a crush on Jonathan

Schmitz.173 Supposedly embarrassed by the revelation of a same-sex crush,

174

Mr. Schmitz left the show and began a three day drinking binge.

On the morning of March 9, 1995, Mr. Schmitz "found a sexually suggestive note from Amedure on his front door."1 75 Mr. Schmitz then "withdrew money from his savings account, and purchased . . .a shotgun and

some ammunition."' 76 Mr. Schmitz drove to Mr. Amedure's trailer and

fatally shot him in the doorway of his trailer.' 77 Mr. Schmitz then called

1 78

911 and reported his crime.

At Mr. Schmitz's trial, the defense argued a diminished capacity defense. 179 The defense maintained that Mr. Schmitz already had "a badly

damaged psyche, was ambushed by the Jenny Jones show . . .and [was]

unrelentingly stalked by Amedure."'c' Even though Mr. Schmitz had been

charged with first-degree murder, the jury returned a verdict convicting him

of second-degree murder.' 8' The court of appeals overturned Mr.

Schmitz's first conviction of second-degree murder, but in the retrial, even

though the defense continued to blame the victim Scott Amedure, Mr.

1 82

Schmitz was once again convicted of second-degree murder.

169.

See generally id.

170.

171.

See generally id.

See "Gay Panic" Defense, supra note 159, at http://www.courttv.com/trials/mckin-

ney/gay-panicjrulingsctv.html.

172. See Michigan v. Schmitz, 586 N.W.2d 766, 768 (1998).

173.

174.

175.

176.

177.

178.

See

See

Id.

Id.

See

See

id. at 768.

id.

Schmitz, 586 N.W.2d at 768.

id.

179. See id.

180.

181.

Id.

See id.

182. See Suffredini, supra note 25, at 280.

Summer, 2003]

SUPREME COURT AND HOMOSEXUALITY

233

The murder of Scott Amedure demonstrates how little is required to suggest that the heterosexual male was provoked by the homosexual. 183 Mr.

Schmitz appeared on The Jenny Jones Show and became aware of Scott

Amedure's attraction towards him.' 84 The only contact between Mr.

Amedure and Mr. Schmitz after their appearance on the talk show was a

"sexually suggestive" letter allegedly left by Mr. Amedure on Mr.

Schmitz's front door. 8 5 The defense took the appearance on the talk show

and this one letter, and manipulated it into a claim that Mr. Schmitz had

been relentlessly stalked by Mr. Amedure.' 86 The use of the homosexual

panic defense allowed the defense to manipulate any possible homophobic

stereotypes the jury members may have had into a justification for the mur87

der of Scott Amedure.1

II.

PREJUDICIAL VIEWS OF AFRICAN-AMERICANS

Beginning with slavery in the United States, African-Americans have

been stereotyped as second-class citizens who have struggled to gain some

sense of equality in this country. 8 8 Originally, the fear of African-Americans began with the fear of slave uprisings. 89 Whites, realizing that this

was a possibility, were frightened that should the slaves unite, they could

potentially overthrow the system of slavery and, in the process, harm the

white slave owners.' 9 ° This idea has translated itself through the generations into American culture.' 9 1

Slavery originally not only meant enslaving Africans, but it also meant

enslaving Native Americans. 9 ' In 1670, an Act by the Virginia state legislature enslaved Native Americans brought into Virginia by land for twelve

years, or if the Native Americans were children, they were enslaved until

the age of 30.113 On the other hand, "negroes" brought into Virginia by

boat were enslaved for life.' 9 4 By 1682, the differences between Native

Americans and Africans were discarded, and the term slave referred to all

non-Christian servants. 19 5 Because of the lack of laborers, slaves were used

183.

See generally id. at 303.

184.

See id. at 279.

185.

186.

187.

188.

189.

190.

191.

192.

193.

194.

195.

See

See

See

See

See

See

See

See

See

See

See

Schmitz, 586 N.W.2d at 768.

id.

Suffredini, supra note 25, at 280.

generally Morgan, supra note 8.

id. at 307-08.

id.

id. at 330.

id. at 328-29.

Morgan, supra note 8, at 329.

id.

id.

CRIMINAL AND CIVIL CONFINEMENT

[Vol. 29:219

to build the foundation of the emerging settlements in America.' 9 6 It did

not really matter if these servants were brought in from other parts of

America or from Africa, "they were both, after all, basically uncivil, unchristian, and above all, unwhite."' 97

Fear of an uprising by African-Americans that could, if not overthrow, at

least disrupt our governmental system has fueled many prejudicial ideas of

African-Americans. 9 8 As slavery increased in Virginia, the legislature

continued to enact laws to not only control slaves, but also to instill the idea

that they were second-class servants.1 99 In 1705, the legislature allowed

"dismemberment of unruly slaves." 2" A problem began to arise when the

new settlers actively tried to convert both Native Americans and Africans to

Christianity.2 0 ' This conversion would do away with the notion of the savage non-Christian.2" 2 Masters began to discourage their slaves from becoming Christians because "it made them proud, and not so good

servants. ' ' 203

One of the biggest concerns for the new settlers was the mixing of the

races. 2°4 Those in positions of authority wanted to ensure the purity of the

20 5

white race by prohibiting sexual relations between whites and Africans.

In 1630, Hugh Davis was ordered to be whipped in front of "'an assembly

of Negroes and others for abusing himself to the dishonor of God and

shame of Christians, by defiling his body in lying with a negro." 20 6 By

1691, the Virginia legislature had enacted a law making interracial marriage

illegal. 2 7 The law was specifically aimed at the "'prevention of that abominable mixture of spurious issue which hereafter may encrease in this dominion, as well by negroes, mulattos, and Indians intermarrying with

English, or other white women.' , 2 8 The law further established that if a

white man did marry a "Negro" he would to be banished from the colony.20 9 If a free white woman gave birth to a child by a non-white man, she

would be fined.2 10 If she could not pay the fine, the woman would be sold

196.

197.

198.

199.

200.

201.

See id. at 296.

See id. at 329.

See generally Morgan, supra note 8, at 308.

See generally id. at 329-34.

Id. at 333.

See id.

202. See id. at 331-32.

203.

204.

205.

Morgan, supra note 8, at 333.

See id. at 333.

See id.

206.

207.

208.

209.

Id.

See id. at 334-35.

Morgan, supra note 8, at 335.

See id.

210.

See id.

Summer, 2003]

SUPREME COURT AND HOMOSEXUALITY

235

for a period of five years, and the child would be a servant to the parish for

a period of thirty years.2 1'

These laws were intended to encourage the idea of racism.2 12 Keeping

the white race pure, while sacrificing the needs and dignity of non-white

races was the ultimate goal of these laws.21 3 These ideas permeated not

only the time of slavery, but continued in the United States well after the

Emancipation Proclamation and into the time of the Jim Crowe Laws in the

south. 2 14 In 1955, a fourteen-year-old African-American boy, Emmett Till,

was kidnapped and killed by two white men in Mississippi. 21 5 The boy was

killed because he whistled at a white woman earlier that week.216 When his

body was found floating in a river it was "unrecognizable, except for a ring

on his hand. 121 7 An all-white jury acquitted the two white men of the

crime, and four months after their acquittal, Life Magazine published an

alleged confession by the two men. 2 18 Slowly, African-Americans through

the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s began to obtain a more equal footing with whites.21 9 As this movement took place, some of the barriers separating the races were eliminated as a violation of equal protection under the

United States Constitution. 2

A.

The Supreme Court and African-Americans

In Loving v. Virginia,22 1 the Supreme Court struck down a statute making it illegal for a white person to marry a black person.2 22 Loving involved

a case where a "Negro woman, and ...

a white man, were married in the

District of Columbia. '223 They then returned to their native State of Virginia, where they were convicted of violating a Virginia statute that forbade

marriage between a "white person" and a "colored person."2'24 The statute

stated: "If any white person intermarry with a colored person, or any

211. See id.

212. See generally id. (keeping the races separate meant keeping the races unequal by

the enforcement of these laws).

213. See generally Morgan, supra note 8, at 329-34.

214. See generally Loving, 388 U.S. I (explaining how the lower court reasoned that the

races were put on separate continents in order to keep the races pure).

215.

See Film Addresses Murder of Emmett Till, CourtTV Online, Jan. 20, 2003, at

http:www.cnn.com/2003/SHOWBIZ/TV/01/20/tv.till.murder.ap/index.htm

[hereinafter Film

Addresses Murder].

216. See id.

217. Id.

218. See id.

219. See id.

220. See generally Film Addresses Murder, supra note 215, at http:www.cnn.comI2003/

SHOWBIZ/TV/01/20/tv.till.murder.ap/index.html.

221.

388 U.S. 1 (1967).

222.

223.

224.

See id.

Id. at 2.

See id. at 4.

CRIMINAL AND CIVIL CONFINEMENT

[Vol. 29:219

colored person intermarry with a white person, he shall be guilty of a felony

and shall be punished by confinement in the penitentiary for not less than

one nor more than five years. 22 5 The trial court judge suspended the

couples' one-year jail sentence, but conditioned it upon them leaving the

State of Virginia for a period of 25 years.22 6 In making his ruling the judge

stated:

'Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and

he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with

his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that

the races shows that he did not intend for the races to

he separated

7

mix.'

22

In upholding the conviction of the couple, the Supreme Court of Appeals of

Virginia stated the reasons for supporting these laws were: "'to preserve

the racial integrity of its citizens,' and to prevent 'the corruption of blood,'

'a mongrel breed of citizens.' and 'the obliteration of racial pride.' "228

In holding the Virginia statute unconstitutional, the United States Supreme Court reasoned that the true purpose behind the statute was to maintain and promote "White Supremacy. "229 The Court concluded that the

the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

statute violated

23 0

Amendment.

As society progresses, many stereotypes still progress with it. 23 1 It is

easier to see stereotypical behavior and allow it to reinforce your prejudice,

than to change your way of thinking about a group of people.23 2 As the

American public becomes more aware of the social injustices that exist for

African-Americans, the court system is less likely to allow the blatant manipulation of jurors with racial stereotypes that paint African-Americans in

a negative light. 233 Racism and bigotry, however, are still thriving in society. The change has been that when an African-American is the victim of a

violent crime, based on racism, it can no longer be justified based on the

victim's race.2 34 One can no longer say that the victim deserved what he

got because of the color of his skin.2 35

225.

226.

227.

228.

229.

230.

231.

232.

233.

234.

235.

Id.

See Loving, 388 U.S. at 3.

Id.

Id. at 7 (quoting Naim v. Naim, 197 Va. 80, 90 (1955)).

See id.

See id. at 12.

See Armour, supra note 7, at 739.

See id.

See id.

See generally King v. Texas, 29 S.W.3d 556 (Tex. Crim. App. 2000).

See id. at 558.

Summer, 2003]

SUPREME COURT AND HOMOSEXUALITY

237

In the high-profile trial of the dragging death of James Byrd, Jr., the

focus was on the white defendants and their racist backgrounds. 236 There

was no way to establish that because of James Bird, Jr.'s race, he somehow

brought it on himself. 237 No matter how racist and prejudiced the jurors

may have been, any defense based on a justification for his brutal death

because of his race would never have been allowed in the courtroom. 238

B.

The Murder of James Byrd, Jr.

On the evening of June 6, 1998, James Byrd, Jr., an African-American

man, attended a party in his hometown of Jasper, Texas.2 39 In the early

hours of June 7th, an acquaintance of Mr. Byrd's saw him riding in the back

of a pick-up truck. 240 The next morning the Jasper police were called to the

discovery of a headless body of an African-American man at a predominantly African-American church outside Jasper, Texas. 2 4 ' The body was

later identified as that of James Byrd, Jr.242 Mr. Byrd's headless body was

found with his clothes tangled around his ankles.24 3 Mr. Byrd's head and

shoulder were discovered further up the road with a trail of blood leading

up the road between the headless body and Mr. Byrd's head and shoulder.2 44 Along the dirt road, police found Mr. Byrd's wallet, a cigarette

lighter engraved with the letters "KKK," and a wrench engraved with the

word "Berry. 2 4 5

On June 8, 1998, a pick-up truck owned by Shawn Berry was stopped for

a traffic violation.2 46 Police searched the truck and found a set of tools that

had the word "Berry" on their handles. 247 DNA evidence would later confirm that blood splatter underneath Mr. Berry's truck matched the blood

type of James Byrd, Jr. 24 8 A search of Mr. Berry's apartment also revealed

blood-stained clothing which later would was later determined to be stained

249

with the blood of James Byrd, Jr.

Shawn Berry, John King and Lawrence Russell Brewer, three white men,

were arrested for the death of Mr. Byrd.'

At trial, Lawrence Russell

236. See id.

237.

238.

239.

See generally id.

See generally id.

King, 29 S.W.3d at 558.

240. See id.

241.

242.

243.

244.

245.

See

See

See

See

Id.

id.

id.

id.

King, 29 S.W.3d at 558.

246. See id.

247.

248.

249.

250.

See

See

See

See

id.

id.

King, 29 S.W.3d at 559.

Jasket, supra note 145, at 512.

CRIMINAL AND CIVIL CONFINEMENT

[Vol. 29:219

Brewer explained how he and the other two men had been out joy-riding the

night they saw Mr. Byrd."' Earlier that night they had used a logging

52 Mr. Brewer

chain to pull up a mailbox and drag it behind their truck.2

explained that after giving Mr. Byrd a ride, they pulled off to the side of the

road and a fight broke out between Mr. Byrd and the three men. 253 The

three men then slashed Mr. Byrd's throat.25 4 Mr. Brewer further testified

that he got in the cab of the truck while Mr. Berry Mr. and King continued

to beat Mr. Byrd.2 55 Mr. Brewer testified that he begged Mr. Berry and Mr.

King not to drag Mr. Byrd with the logging chain as they had done with the

mailbox earlier that evening.2 56 Despite his pleas, Mr. Byrd was tied to the

back of the truck with the logging chain and drug down the logging road

until his head and shoulder were severed from his body.2 57 Evidence would

later illustrate that Mr. Byrd was alive during the dragging.2 58

At the trial of Mr. King, the prosecution focused on the racial animosity

that the three men had toward African-Americans.2 5 9 This was illustrated

through Mr. King's position "as the 'exalted cyclops"' of a white supremacist gang in prison and a number of Mr. King's tattoos.26 ° Mr. King's tattoos included images of a swasticka, and "a black man with a noose around

his neck hanging from a tree. '"261 Mr. King had allegedly been known to

show these tattoos and boast "'See my little nigger hanging from a

tree.' ",262 At trial, a "gang expert" testified that from information gathered

at John King's apartment, it was obvious he was trying to start a chapter of

the Confederate Knights of America in Jasper, Texas.2 63 In order to gain

publicity, he planned on doing something "public" on or around July 4,

1998.2 4 By leaving the body in front of an African-American church he

intended to "strike terror in the community. '"265

251. See The Brutal Murder of James Byrd, Jr. of Jasper, Texas NAACP, Sept. 17,

1999, at http://www.texasnaacp.org/jasper.htm#brewer (last visited Feb. 2, 2003) [hereinafter Texas NAACP].

252. See id.

253. See id.

254. See id.

255. See id.

256. See Texas NAACP, supra note 251, at http://www.texasnaacp.org/jasper.

htm#brewer.

257. See id.

258. See id.

259. See King, 29 S.W.3d at 559.

260. Id.

261. Id. at 560.

262. Id.

263. See id.

264. See King, 29 S.W.3d at 560.

265. Id.

Summer, 2003]

SUPREME COURT AND HOMOSEXUALITY

239

At Mr. Brewer's trial, the prosecution focused on racially motivated letters written by Mr. Brewer to Mr. King. 26 6 In these letters, references were

made to the term "roll a tire. '"267 Mr. Brewer testified that this was a reference to "a fellow inmate's dream to put a black man in a tractor tire and roll

him down a hill." 268 Ultimately Mr. King was found guilty of kidnapping,

murder, and was sentenced to death.2 69 Mr. Brewer was also convicted of

murder and sentenced to death, while Mr. Berry was found guilty of murder

but spared the death penalty.27 °

Unlike the murder of Matthew Shepard, the focus of the trial for the

murder of James Byrd, Jr. was on the hatred the defendants had for the

victim. 2 71 The defendants offered no justification for the crime. 272 The

only reason the crime had been committed was because of the color of Mr.

Byrd's skin.27 3 Unlike Matthew Sheppard's trial, there would not have

been an African-American panic defense available to the murderers of

James Byrd, Jr.2 74

C.

Hate Crime Legislation

Hate Crime legislation began in 1969 with a hatecrime statute as part of

the civil rights legislation. 275 The statute protects anyone who is not permitted to participate in federally protected activities because of their "race,

color, religion, or national origin. 2 7 6 The language of the Hate Crimes

Statistics Act of 1968 specifically does not include claims based on sexual

orientation. 7 7 In 1990, the Hate Crimes Statistics Act was passed. 78 The

purpose of the statute was to require the Attorney General to gather and

publish statistics on crimes based on "race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, or ethnicity.

279

Also in 1994, the Hate Crimes Sentencing Enhancement Act was passed

by Congress, providing an increase in the defendant's sentencing by three

266. See Texas NAACP, supra note 251,

htm#brewer.

267. Id.

268. Id.

269. See Jasket, supra note 145, at 512-13.

270.

271.

272.

273.

See

See

See

See

274.

See Suffredini, supra note 25, at 310.

at http://www.texasnaacp.org/jasper.

id.

generally King, 29 S.W.3d at 556.

generally id.

generally id.

275. See Andrew M. Gilbert & Eric D. Marchand, Note, Splitting the Atom or Splitting

Hairs - The Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 1999, 30 ST. MARY'S L.J. 931, 953 (1999).

276.

277.

278.

279.

Id. at 953.

See id. at 957.

See id. at 955 (The Act was codified in 1994).

See id.

CRIMINAL AND CIVIL CONFINEMENT

[Vol. 29:219

levels. 28" The sentence may be increased by three levels if it is determined

beyond a reasonable doubt that the victim was intentionally selected because of his or her "actual or perceived race, color, religion, national origin,

ethnicity, gender, disability, or sexual orientation." 2 ' Although the Hate

Crimes Sentencing Enhancement Act provides prosecutors with a tool

against hate crimes, as of 1999, out of 48,020 total sentence enhancements,

only 58 were successful.2 8 2

The legislation already passed is not without its problems. 28 3 In order to

enforce the Hate Crime Statute of 1960, the crime must be linked to a federally protected activity.2 84 The six federally protected activities include:

(1) enrolling in or attending a public school or public college; (2) participating in or enjoying a benefit, service, privilege, program, facility or activity provided or administered by a state government; (3) applying for or

enjoying employment; (4) serving as a grand or petit juror of any state; (5)

traveling in or using any facility of interstate commerce; or (6) enjoying

the goods or services of certain places or accommodation.285

In order to prosecute under 18 U.S.C. § 245, enacted as part of the Civil

Rights act of 1968, the person must be engaged in a federally protected

activity, and that activity must be the reason for the crime.28 6 This statute

also does not include crimes based on gender, disability, or sexual orientation.2" Therefore, the principle federal hate crime legislation only covers

crimes committed because of "race, color, religion, or national origin. 2 88

III.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE OF STEREOTYPES OF WOMEN

In the past, women were often considered second-best to men. For years,

women did not have the right to vote, and were denied many of the same

rights to which men were entitled. 289 Traditionally, when a man and woman married, it was viewed as the two coming together as one. 290 Generally, the one unit that resulted from the marriage was controlled by the

man. 2 9 1 The view of women as nurturers predominated with the underlying

29 2

idea that "women give themselves, their bodies, their pleasures to men."

280.

281.

282.

283.

284.

285.

286.

287.

288.

289.

office,

290.

291.

292.

See Gilbert & Marchand, supra note 275, at 957-58.

Id. at 958 (citing 28 U.S.C. § 994 note (1994)).

See id. at 943-44.

See id. at 954.

See id.

Gilbert & Marchand, supra note 275, at 954.

See id.

See id. at 954-55.

Id. at 955 n.99.

See Frontiero, 411 U.S. at 685 (explaining how slaves and women could not hold

serve on juries or hold property in their own names).

See id. at 684.

See id.

STONG ET AL., supra note 42, at 132.

Summer, 2003]

SUPREME COURT AND HOMOSEXUALITY

241

Along with this idea of women being servants to men came certain sexual

scripts.2 93 Women were taught that sex was good in marriage or a committed relationship, but "bad" outside of marriage.2 94 Sex was something to be

saved for your husband, and if a woman did not save herself for marriage,

she would develop a "bad reputation. ' 295 "Women are supposed to remain

pure and sexually innocent."29' 6 The traditional roles indicated that men

wanted sex, while women were looking for love and a relationship.2 9 In a

sexual relationship, women were viewed as the passive partner, while men

were viewed as the active partner.29 8 Because women were viewed as being dominated by men, most laws did not protect women. 299 The legal

system and the rights afforded to the citizens of the United States were

mainly aimed directly at men. 3" In 1873, the views of women at that time,

were expressed in Bradwell v. Illinois.3 °1 "'The paramount destiny and

mission of woman are to fulfil the noble and benign offices of wife and

mother. This is the law of the Creator.' "302

By the 1960s and 1970s, at the same time the Civil Rights Movement

was gaining attention for equal rights of African-Americans, the feminist

movement of the sixties and seventies began a new way of looking at women as men's equals.3 °3 To reflect society's changing views of women,

courts began to change the laws that restricted the constitutional rights of

30 4

women.

A.

Supreme Court's View of Women

Nearly a hundred years after its view of women was illustrated in

Bradwell v. Illinois, the Supreme Court readdressed society's view of women. 30 5 In Frontiero v. Richardson, the Court addressed the issue of a

woman claiming her husband as a dependent.30 6 The Court quoted

Bradwell v. Illinois, and indicated that the views stated in that decision allowed statutes to be written that were "laden with gross, stereotypical dis293.

See id.

294.

295.

296.

297.

298.

Id.

Id. at 132.

Id.

See STRONG

See id.

299.

See Fronteiro,411 U.S. at 685.

ET AL.,

supra note 42, at 132.

300. See id. at 684-85.

301. See id.

302.

Id. (quoting Bradwell v. State, 16 Wall. 130, 141 (1873)).

303. See Andrew Z. Soshnick, Comment, The Rape Shield Paradox: Complainant Protection Amidst Oscillating Trends of State Interpretation, 78 J. CRIM. L. & CRIMINOLOGY

644, 647 (1987).

304.

See id.

305.

See generally Frontiero, 411 U.S. 677.

306.

See id. at 677.

CRIMINAL AND CIVIL CONFINEMENT

[Vol. 29:219

tinctions between the sexes."3 7 The Court stated that "the position of

women in our society was, in many respects, comparable to that of blacks

under the pre-Civil War slave codes. ' 30 8 "There can be no doubt that our

Nation has had a long and unfortunate history of sex discrimination. Traditionally, such discrimination was rationalized by an attitude of 'romantic

paternalism' which, in practical effect, put women not on a pedestal, but in

a cage.

30 9

Changes in societal views of women forced the court system to change

many of its laws in order to treat women on an equal footing with men.3 0

The Supreme Court began to view classifications based on sex and race as

"inherently suspect" classes. 31 1 This meant that any statute that affected the

rights of people based solely on race or sex would be subject to "strict

judicial scrutiny. ' 312 The Court stated,

since sex, like race and national origin, is an immutable characteristic determined solely by the accident of birth, the imposition of special disabilities upon the members of particular sex because of their sex would seem

legal burdens should bear

to violate "the basic concept of our system that313

some relationship to individual responsibility."

The changing views of society, combined with the willingness of the Supreme Court to recognize the discrimination of women, led to many reforms, including reforms of laws governing prosecutions for rape.3 14

Historically, rape prosecution was as much a trial of the alleged victim as it

was of the defendant. 3 5 During the Victorian era, it was suggested that

women who claimed to have been raped should submit to a psychological

evaluation before trial. 316 "Men's fear of the innocent man being unjustly

accused of rape drove the common law. The testimony of rape victims was

greatly distrusted due to fear that women would lie about the consensual

nature of the sex."' 3 17 The past sexual history of the alleged victim was

relevant in rape trials where consent was the defense, because courts considered it more likely that a woman who had consented to sex on a previous

occasion would have consented to sex in the instance at issue. 3 8 Therefore,

307.

308.

309.

310.

311.

312.

313.

(1972)).

314.

Id. at 685.

Id.

Frontiero,411 U.S. at 684.

See id. at 688.

See id.

Id.

Id. at 686 (citing Weber v. Aetna Casualty & Surety Co., 406 U.S. 164, 175

See Soshnick, supra note 303, at 647.

315. See Heather C. Brunelli, Note, The Double Bind: Unequal Treatmentfor Homosexuals Within the American Legal Framework, 20 B.C. THIRD WORLD L.J. 201, 207 (2000).

316.

317.

318.

See Soshnick, supra note 303, at 650.

Brunelli, supra note 315, at 208.

See Soshnick, supra note 303, at 652.

Summer, 2003]

SUPREME COURT AND HOMOSEXUALITY

243

courts further victimized rape victims by permitting past sexual behaviors

or predispositions to be entered into evidence.31 9

These obstacles resulted in many women not reporting incidents of

rape. 32 0 As a result, both state and federal courts passed rules of evidence

designed to restrict the sexual history of the victim form being heard at

trial.32 1 In 1978, Congress enacted Rule 412 of the Federal Rules of Evi

dence "which excludes from evidence all reputation and opinion testimony

concerning a rape complainant's prior sexual conduct. 322 States, in turn,

passed their own statutes, called rape shield statutes, to protect women from

becoming the victim during a trial for rape. 3 23 The focus of most of the

rape shield statutes was to prevent the hostile confrontation of the victim in

the courtroom.3 24 Congress and the states reacted to the changing views of

3 25

women in society and sought to create protections for women as a group.

B.

The Rape and Murder of Barbara Williams

In November 1991, after family and neighbors had been trying to obtain

entry into the home of Barbara Williams, a neighbor crawled through a

window into Ms. Williams' apartment.32 6 Inside, the neighbor found Ms.

Williams dead, with multiple stab wounds and an electric cord tied around

her neck. 327 Along side Ms. Williams were two of her children, who were

still alive but had received at least twenty-five stab wounds.32 8 One of the

children explained that a man came through a window and attacked the

family.3 29 Medical tests would later reveal that Ms. Williams had been sexually assaulted both vaginally and anally.33 °

Sharob Clowney, who was later arrested for Ms. Williams' murder, was

at first reluctant to tell the truth about what had happened between himself

and Ms. Williams. 3 His first explanation for the cut on his hands was that

a mirror had broken and caused the wounds. 332 He later told his family that

he had struggled with Ms. Williams and stabbed her children.3 33 At trial,

Mr. Clowney's defense sought to introduce evidence that Ms. Williams was

id.

id. at 651.

generally id.

id. at 645.

generally Soshnick, supra note 303.

319.

320.

321.

322.

323.

See

See

See

See

See

324.

See generally id.

325.

326.

327.

328.

See generally id.

New Jersey v. Clowney, 690 A.2d 612, 615 (N.J. 1997).

See id.

See id.

329.

See id.

330.

331.

See id. at 616.

See Clowney, 690 A.2d at 617.

332.

333.

Id. at 615.

See id.

CRIMINAL AND CIVIL CONFINEMENT

[Vol. 29:219

known to trade sex for drugs.334 However, applying New Jersey's Rape

Shield Statute, the lower court held that evidence was inadmissible at

trial.3 35 The jury subsequently found Mr. Clowney guilty of "purposeful or

knowing murder, ...

felony murder, . . .aggravated sexual assault ...

attempted murder, ...

possession of a weapon, a knife, for unlawful purposes .... and possession of a weapon, the same knife, under circumstances

not manifestly appropriate for such lawful uses as it may have. 3 36

On appeal, Mr. Clowney sought to have the lower court's decision to

exclude Ms. Williams' past sexual conduct overturned.3 37 Mr. Clowney

further argued that because Ms. Williams was deceased, the Rape Shield

Statute should not have been applied.3 38

In addressing Mr. Clowney's claims, the appeals court first looked to the

language of the New Jersey Rape Shield Statute which states: "[e]vidence

of the victim's previous sexual conduct shall not be admitted nor reference

made to it in the presence of the jury except as provided in this section."3'39

The statute further states that in making its decision to include or exclude

the evidence, the court will take into consideration whether "the probative

value of the evidence offered substantially outweighs its collateral nature or

the probability that its admission will create undue prejudice, confusion of

the issues, or unwarranted invasion of the privacy of the victim."3 4

Before specifically addressing Mr. Clowney's claim, the court looked to

the past history of rape shield statutes.3"4 ' The court recognized that many

state legislatures had enacted statutes to prevent the rape victim from being

unduly victimized on the witness stand during cross-examination.3 42 The

court further stated: "By ensuring that juries will not base their verdicts on

prejudice against the victim, the statutes enhance the reliability of the criminal justice system. '34 3 The court stated that prior to the enactment of rape

shield statutes, trials often turned into an invasion of the victim's privacy

and a "character assassination." 34

334.

335.

See id. at 617-18.

See id. at 619.

336.

337.

338.

339.

See Clowney, 690 A.2d at 613-14.

See id. at 618.

See id.

Id. (citing N.J.S. 2C:14-4).

340.

Id. (citing N.J.S. 2C:14-4).

341.

342.

343.

344.

See Clowney, 690 A.2d at 620.

See id. at 619.

Id. at 618.

Id.

SUPREME COURT AND HOMOSEXUALITY

Summer, 2003]

C.

245

State in Interest of M.T.S.

In 1992, the Supreme Court of New Jersey heard a sexual assault case

involving a fifteen-year-old girl and a seventeen-year-old boy.34 5 The boy

had been living with the girl's family for some time before the night of the

alleged assault.3 46 The relationship between the boy and the girl had been

"'leading on to more and more.' "

The two offered different views of the

348

night in question.

According to the boy, she invited him into her room

and initially freely participated in the sexual conduct.34 9 The girl alleged

that he forced himself upon her without her consent.3

The issue for the court was how much force was necessary to be considered a sexual assault.3 51 The only force used during the assault was the

requisite force for the boy to vaginally penetrate the girl.3 52 The language

of the New Jersey statute defined "'sexual assault' as the commission 'of

sexual penetration' 'with another person' with the use of 'physical force or

coercion.' ,353 The appellate court determined that in order to be consid-

ered a sexual assault more force was needed than the minimum force required for penetration. 354 The Supreme Court of New Jersey ultimately

held that any force used "in the absence of affirmative and freely given

permission to the act of sexual penetration" constituted sexual assault under

the New Jersey statute. 5

In reaching its determination, the court looked at the historical aspects of

proving rape.356 Quoting Lord Hale, the court stated that historically, "to

be deemed a credible witness, a woman had to be of good fame, disclose

the injury immediately, suffer signs of injury, and cry out for help."3' 57 The

court also noted that historically courts distrusted the victims, "'assuming

that women lie about their lack of consent for various reasons: to blackmail

men, to explain the discovery of a consensual affair, or because of psychological illness.' "358

The court further recognized that this focus on the victim's character

minimized the "importance of the forcible and assaultive aspect of the de345. See generally State in Interest of M.TS., 609 A.2d 1266 (N.J. 1992).

346. See id. at 1267.

347. Id. at 1268.

348.

349.

350.

351.

See

See

See

See

id. at

id. at

State

id. at

1267-68.

1268.

in Interest of M.TS., 609 A.2d at 1267.

1269.

352. See id. at 1268.

353. Id. at 1269.

354. See id. at 1269.

355. State in Interest of M.T.S., 609 A.2d at 1279.

356. Id. at 1270.

357. Id. at 1271.

358. Id.

246

CRIMINAL AND CIVIL CONFINEMENT

[Vol. 29:219

fendant's conduct."3 5 9 Successful prosecutions for rape turned not only on

the defendant, but on the nature of the victim's response.36 ° With the

change in focus away from the victim and toward the defendant, the courts

in New Jersey paved the way for rapid reform in rape prosecutions.36 '

New Jersey's viewpoint, which began to be reflected in other rape reform

legislation, allowed some of the stereotypes about women to begin falling

apart.362 The court system recognized that women had been treated as

poorly as slaves, and rethought women's roles in American culture.36 3 The

change in the court's view of women is no where more obvious then in the

reform of the laws against rape. 36 4 Rape shield laws, unlike the Homosexual Panic Defense, turn the focus onto the perpetrator of the crime, and not

36 5

on the victim.

IV.

THE SUPREME COURT'S SECOND CHANCE TO PROTECT THE

RIGHTS OF HOMOSEXUALS

In 2002, the United States Supreme Court granted certiorari to a Texas

case involving an anti-sodomy statute. 36636In Lawrence v. State,367 the Court

of Appeals of Texas upheld the constitutionality of a Texas anti-sodomy

statute. 368 "John Geddes Lawrence and Tyon Garner were convicted of engaging in homosexual conduct. 3 69 Both men entered pleas of non contendere, so the officer's conduct in arresting the two men was not

challenged.370 The details surrounding the arrest of the two men were not

part of the court's record. 3 7 ' The State of Texas defines deviate sexual

intercourse as "any contact between any part of the genitals of one person

and the mouth or anus of another person; or the penetration of the genitals

or the anus of another person with an object. ' 372 Texas further designates

"engaging in deviate sexual intercourse with another individual of the same

sex" as a class C misdemeanor.37 3

359.

360.

361.

362.

363.

Id. at 1272.

See State in Interest of M.T.S., 609 A.2d at 1272.

See id. at 1274.

See generally Frontiero, 411 U.S. at 690-91.

See id. at 685.

364.