Pompeii Uncovered: A History of Repression Pompeii is a site

advertisement

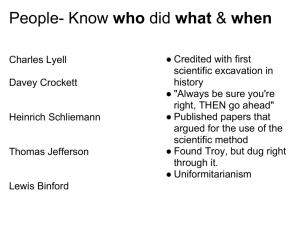

Pompeii Uncovered: A History of Repression Pompeii is a site predominantly known to the public for three reasons: its tragic destruction and simultaneous preservation, its remarkable story of excavation, and its reputation as a hotbed for debauchery. These three elements are key parts of the historical discourse surrounding the Roman town, creating a narrative that has now been disseminated to the wider public. When Pompeii was first uncovered, archaeology was still in its infancy and religious mores were the main guiding principles within society, influencing our initial impressions of the site. As the archaeological method and the social ethos changed, so did the interpretations of the town, reflected in art and literature. The Vesuvian towns became an obsession for artists and antiquarians alike, capturing the public imagination as a ‘window on the ancient world’.1 Walking the streets of the uncovered city was seen as the equivalent of traveling into the past, coming in contact with the world of our ancestors. Through its uncovery, Pompeii developed into a cognitive landscape, encoded with meaning. In more recent years, academic interest has turned to the study of Pompeii as a paradigm to understand present-day issues. The ancient world became used for analysing contemporary themes such as sexuality, sin and divine punishment. The deployment of Pompeii as a location for artistic works can be understood as creating a setting for the encryption of modern values that would otherwise be considered taboo. These often have no immediate connection to the known customs or viewpoints of the earlier occupants of the area, but have emerged from years of philosophical reflection grounded in a Christian framework. This essay will shed light on the various ways in which the site of Pompeii and its artefacts were imbued with cryptic layers of significance after its resurrection in the eighteenth century. The concept of cognitive historiography will be explored as it pertains to the site of Pompeii becoming a repository for the repressed sentiments of modern society. This includes its use as a reminder of man’s innate lot in death and as a symbol for sexuality and repressed desire. This will illuminate the dissemination of the myths of Pompeii, showing how the image we see today was formed. The study of cognitive archaeology and historiography is quite a recent affair, stemming from the debates between processual and post-processual theories within the disciplines. The cognitive method focusses on the ‘thinking practices’ of past civilizations and how we are able to perceive these through literary and material culture.2 The idea behind this is that we all possess a cognitive map upon which we graph our experiences. These interior thoughts are then expressed in the creations shaped by individual persons.3 For members of a singular society certain elements will overlap, due to a number of common traditions and historical processes. Through analysing their cultural remains, we can then understand certain aspects of the collective social ethos that they belong to. This theory has been criticized by other schools, and most notably by processual archaeologist Lewis Binford. He states that 1 Owens http://science.nationalgeographic.co.uk/science/archaeology/pompeii/ accessed 5/5/2013 Nersessian 1995:19 3 Renfrew 1982:27 2 ‘paleopsychology’4 is not a valid field of study as the mind is universal, and thus it is the environment, not the human actors, who determine human behaviour and can effect change.5 In relation to Pompeii cognitive theories have been employed to determine whether or not our modern interpretation of the ancient evidence coincides with the inhabitants’ own world views. Through such studies many impressions of the town have been revealed to be our own retrojected sensitivities. So although the idea of inferring ancient thought from artefacts is debateable, if we reverse the focus of this research frontier, it becomes a stimulating method to explore how the societies to which the archaeologists and historians belong interact with the sites of the ancient world. It reflects how they think about their own society, in particular through their use of the past. By looking at our own modern discourse on Pompeii and inferring the ideologies behind it, we can better understand how our own systems of thought have developed and where their source truly lies. This requires an interdisciplinary method including elements of historical, archaeological and psychology to analyse our own adaptations of Pompeii and the mythology we built around it. This is especially important when it comes to ‘taboo’ subjects such as mortality and sexuality, which are repressed in most modern day-today discourse and are therefore expressed through alternate means. By extracting these from the narratives of the past we can better understand the paradigms of the interpreters and how they conceived the taboo subjects and interacted with the ancient site. The primary way in which Pompeii appears in the ancient sources, is as a site of tragedy and destruction. Catastrophe struck the Roman colony in August 79 AD when Mount Vesuvius erupted into a whirlwind of ash and fiery hot gasses, submerging the surrounding cities in layers of pyroclastic material. The image of the eruption as a ‘storm of fire’ as described by Campanian poet Statius in the first century AD has remained with us for centuries, dramatizing the eruption and its aftermath.6 The episode described so eloquently in Pliny the Younger’s letters as ‘a cloud rising from the mountain raising in a sudden blast’, has survived in the public imagination to the post-classical period. This cataclysmic event has since been embraced by artists as an embodiment of ‘the Sublime’, exemplifying the terrifying and magnificent power of nature.7 According to Burke’s concept of ‘the Sublime’ this term did not merely describe something that was beautiful or aesthetically pleasing, but it held an inherent existential question and a compelling necessity to react. This instinctive response is one of instant repulsion and pain at the sight of something so jarring. Simultaneously the viewer feels attraction to its power and a delight in knowing he is not embroiled in the horror.8 It underscores the vast emptiness and silence that occurs after a cataclysmic event, the ‘erasure of the human presence’.9 In the eighteenth and nineteenth century this took the form of dramatic landscapes. Such images of the desolate Roman town falling to ruin, become repositories for our own terrors, a way to externalise them by displacing them onto an outlandish scene. John Martin’s painting ‘The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum’ for example depicts a nocturnal apocalyptic scene where the human element is overshadowed by the 4 Thomas 2004:180 Abramiuk 2012:44 6 Statius Silvae 3.5.72 7 Leggio http://www.nccsc.net/essays/pompeii-and-historical-imagination accessed 24/04/2013 8 Burke 1827:110 9 Seydl in Gardner Coates 2012:22 5 1 destructive force of the mountain. This served as an evocative image of the ‘awe inspiring power of nature’ and its ability to create and destroy.10 However, these images never directly displayed the loss of life, choosing instead to focus on the visual and emotional impact of the events.11 Through art and literature populations were able to build a connection to the site, making it a symbol for many later disasters, even into our own time.12 The ability of the site to ‘express the unspeakable’ today extends beyond the power of nature to the human disasters of the Holocaust and Hiroshima, providing a shifting metaphor adapting to contemporary needs.13 The sheer potential for natural forces to completely overwhelm human life remains a universal threat, spanning across time. Through stories, the site becomes more than just a repository for abstract concepts of the Sublime and mortality. The ruined city is populated with recognizable characters allowing the public to connect with it on a personal level, regardless of the characters’ non-existence in reality. It is also for this reason that certain figures featuring in fictional accounts of the site survive as archetypes for later readers. They become the tragic heroes in the great theatrical drama that befell the town. One of the most popular of these figures is the blind slave girl Nydia, introduced in Bulwer Lytton’s novel ‘The Last Days of Pompeii’. She guided her mistress and admired master to safety before committing herself to death at sea. A second is the Roman sentry for whom no conclusive archaeological evidence has been found, but who nonetheless features in a number of works both fictional and supposedly factional. He has come to represent the unwavering devotion and discipline of the Roman army and by proxy other groups that associate themselves with it. These two characters show the ability of some individuals and groups to remain undeterred by the power of a force greater than themselves.14 They represent the Victorian ideal of suppressing baser instincts in order to better the society. The stoic pair came to have ‘symbolic importance in the context of other disasters’15, including those that were not natural such as war. In these situations Nydia and the sentry represent the honourable course of action through persevering in the face of death, a romanticized example presented to the general public. Beyond being an artistic and literary motif, Mount Vesuvius became a vehicle of divine retribution in the minds of the public.16 The Christian motif of the day of reckoning is reflected back onto a primarily pagan society through dissemination in written sources and artistic representations. These visions do not necessarily coincide with the ancient perspective of the event, but are more likely a modern projection. They fit more clearly with Christian notions of God’s capacity to destroy and subsequently regenerate, as in the great deluge.17 Pompeii itself has no evidence of a widespread Christian population, so these sentiments indicate a later belief system being transposed on ancient 10 Hales & Paul 2011:13 Ling 2009:41 12 Getty Museum http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/pompeii/ accessed 25/02/2013 Pliny the Younger Ep.6.16 13 Hales & Paul 2011:341-344 14 Leggio http://www.nccsc.net/essays/pompeii-and-historical-imagination accessed 24/04/2013 15 Hales & Paul 2011:13 16 Landlow http://www.victorianweb.org/art/crisis/crisis1b.html accessed 25/02/2013 17 Hales & Paul 2011:13 Grant 1975:33 11 2 Pompeii. Although most ancient sources simply refer to the destruction as a tragic but remarkable event18, we do see the notion of a divine cause extend beyond the Judeo-Christian understanding of the site into the accounts of later Roman scholars. The late first century historian Plutarch, for example, in his treatise on Divine Vengeance, wrote that the divinely inspired oracle had foretold the doom of Pompeii.19 This however should not be seen as the equivalent of the Christian motif of sin and retribution, which holds the innate necessity for the transference of guilt. In the second century BC the Sibylline Oracles, believed to be composed by the Jews of Alexandria, noted a great eruption that would destroy the Campanian region. 20 This prediction according to Shanks was easily re-interpreted after the tragedy from a Jewish standpoint as evidence for the eruption being a display of ‘the anger of the God of heaven’. 21 His two main sources of evidence for this were the references to Sodom and Gomorrah in relation to the events at Pompeii in the second century Christian writer Tertullian’s Apologies; and the graffiti scratched into a Pompeian wall painting not long after the event stating ‘Sodom and Gomorra’.22 This could imply a connection between the licentious reputation of the town and its ultimate ruin. After the excavation, the town became more manifestly appropriated as a setting for projecting contemporary anxieties about our own vices and the final judgement. An example of this can be seen in Bulwer-Lytton’s comparison between the town upon its destruction and the darkness and fire of hell.23 A second anxiety, which is evident in modern discourse about Pompeii, is man’s fear of his own mortality. This is most clearly reflected in the interest for the plaster-casts, preserving the semblance of the inhabitants of Pompeii in their moment of death. They appeared at a time when preservation was taking its place in the historical consciousness. Early on they were presented as a scientific method by which more evidence could be gained about the site.24 Its potential for attracting public interest was only realized later, after photographs had been disseminated through mass media.25 Since the inception of this method in the 1860s, to recreate the forms of human bodies, the plaster casts have continued to captivate the attention of audiences, in contrast to the fluctuating interest that other aspects of the site evoke.26 They are seen as a way to counteract the constant degradation of our knowledge of ancient sites, and more personally, a way to deter the loss of the individuals who lived in them. In our fear of being forgotten we feel the need to preserve the memory of the lives of those who preceded us. Through our personal identification with these individuals they gain a posthumous life. This creates a dormant intimacy between the living and the deceased that is rekindled upon the uncovering of their imprints.27 The excavation and reconstruction of the site creates a tension between the factual recording and the conceptual recreation of the ancient world. The plaster casts and the site more generally are a constant reminder of our own ephemerality as well as our ability to transcend death 18 Example: Cassius Dio, Roman History 66.21-24 Plutatch, Moralia 556 20 Sibylline oracle book IV 169-174 21 http://www.jpost.com/Israel/Pompeiis-destruction-Godly-retribution 22 House IX.1.25 23 Bulwer-Lytton Book V Chapter 8 24 Living statues 25 http://www.interpretingceramics.com/issue008/articles/06.htm 26 Getty Book 218 27 Bridges 19 3 through memory. The paradoxical ability of the eruption to simultaneously destroy and safeguard the site for later generation would become one of the main ways in which the site of Pompeii was defined in the post-classical period, especially in the minds of archaeologists and historiographers.28 These casts are often interpreted as the physical bodies of the victims or as ‘statues’29, in reality they are anti-bodies, evidence for the cavities left behind by the long since decomposed human remains.30 They represent a lack of matter, but through their exposition as sculpture they become recognized as works of art.31 Their ability to arouse ‘necromantic pathos’ in the viewer, is used to the advantage of many curators and artists, to incite an identification between the viewer and the deceased.32 These casts allow us to empathize with individual bodies, creating a non-historical link between the viewer and the tragedy.33 We become witnesses to the most isolated instants of the victim’s life, and yet these figures are given no right to privacy, having become artefacts or works of art. Mary Beard describes this as a modern voyeuristic obsession with these chalky white figures forever stuck in limbo between death and life.34 An example of this can be seen in Alan McCollum’s work, ‘The Dog of Pompeii’, his repetitive process of copying the cast of the writhing animal was meant to represents the ‘sad absence of a whole world we’ll never retrieve again’.35 The impression given is rather one of sinister discomfort in witnessing a moment of utter pain and torment. He is forcing the viewer to engage with the urge to return to an earlier state of being often through re-enacting traumatic events, termed by Freud as the death drive.36 The modern methods used would normally be juxtaposed with the ancient material, but in this case they become inherent to their visualisation by the general public. The plaster casts become the physical bodies of the deceased. The reconstructed roads are equated with those walked upon by the Pompeians themselves, although the context has been completely altered. A taboo theme that has been in the forefront of Pompeian scholarship since its uncovering is that of sexuality. Classical settings had long been used to enable the exploration of erotic themes in art, subjects that would have been considered inappropriate in a contemporary context.37 By placing these elements in a distant past they become acceptable additions to the artistic repertoire. The Romans were, and often still are, widely believed to have taken part in much debauched behaviour, evidenced by tales of orgies, Catullus’ suggestive poetry and a series of overindulgent emperors. The material remains in Pompeii served to reiterate this view to the wider public, inciting a dual reaction of fascination and simultaneous repugnance. Upon their unveiling in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries these artefacts were viewed as ‘disreputable objects of pagan licentiousness’.38 The story goes 28 Hales & Paul 2011:1 Dwyer 2013, viii 30 BBC http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-20407286 accessed 21/04/2013 31 Leggio http://www.nccsc.net/essays/pompeii-and-historical-imagination accessed 24/04/2013 32 Bridges in Hales & Paul 2011:90 33 Seydl in Gardner Coates 2012:22 34 Beard 2008:7 35 Bartman & Lawson 1996:3 36 Freud 1987:308 37 Getty Museum http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/pompeii/ accessed 25/02/2013 38 De Caro 2003:12 29 4 that when the Bourbon king, Charles, and his court were holding a formal visit to the excavation they saw the statue of Pan copulating with the she-goat being uncovered, and Charles was so mortified by the image that he halted the excavation and confined the statue to a cupboard.39 This tale is a testimony of the ‘collision of worlds’ that occurred when the excavators uncovered the various ‘erotic’ artefacts of the ancient town.40 The sexual imagery proliferating in the Vesuvian towns was believed to substantiate a decadent lifestyle, where pleasure was the main goal of life. This also fit into their theory of the eruption of Vesuvius being a manifestation of divine punishment for Roman vulgarity. However, this theory does not coincide with the rest of the archaeological evidence which suggests a highly productive town.41 As stated above, the moralistic frameworks of sin and prurience are concepts that emerged after the destruction of Pompeii, and must be seen as anachronistic views of Pompeian imagery.42 In these early periods the finds were not analysed in order to better understand Roman ideas on sexuality, but rather to validate the view of history held by those in charge of the excavation. The cognitive agency of these artefacts has been shaped by the way in which later audiences were ‘socialized to perceive ancient sexuality ’.43 An example of where this juxtaposition of viewpoints is evident in the history of the Gabinetto Segreto, or Secret Cabinet, a separate collection of artefacts from Pompeii and Herculaneum kept in the Naples National Archaeological Museum. Initially this collection simply held all items that were deemed ‘pornographic’ in the sense that they contained scenes of nudity or alluded to the sexual act. Much of what was held by the Bourbons and their early site leaders to be perverse would have been innocent images in the eyes of a Pompeian. Phallic images were apotropaic and often meant to stimulate ridicule, while many images featuring nudity depicted mythological scenes meant to manifest the sacred sphere. Even in more recent years, with the re-opening of the cabinet in the early 2000s, the taxonomy still reflects our own sense of sexuality and morality rather than its original context. Although the exhibit is now open to public view, it is still presented behind a locked gate, distinct from its original domestic, commercial or ritual context. The collection undermines our assertion of having entered an era of ‘sexual liberation’ as opposed to earlier oppression, bringing our own categorization of ancient materials into question.44 It seems to reflect an ever-changing state of mind rather than a fixed physical place.45 Even publications highlighting the inaccurate marginalization of erotic artefacts make a division, not necessarily prolific in Roman Pompeii itself. An example of this is Varone’s separation of Non-Eroticism, Public Displays, Manifestations in the Private Sphere and Manifestations in the Sacred Sphere: an artificial division which seemingly contradicts his assertion of sexuality pervading ancient life with a sense of ‘simplicity, spontaneity and naturalness’.46 The categories would have been far more fluid with 39 Harris 2007:47-48 Ancient Digger http://www.ancientdigger.com/2012/05/pompeii-erotic-art-and-roman-sexuality.html accessed 21/04/2013 41 Grant 1975:66 42 Seydl in Gardner Coates 2012:16 43 Ancient Digger http://www.ancientdigger.com/2012/05/pompeii-erotic-art-and-roman-sexuality.html accessed 21/04/2013 44 Fisher & Langlands in Hales & Paul 2011:302 45 Beard in Gardner Coates 2012:66 46 Varone 2000:9 40 5 phallic images for example having a dual function evoking laughter, symbolizing the god Priapus and signifying fertility and protection. It is clear then that sexuality is not an a-historic concept, and that the distinction of sexual artefacts is a way for scholars to make sense of something seen as foreign, often essentializing it in the process.47 The site’s ability to invoke our own inner desires is brought to the psychological plane in the writings of Gautier and Jensen. The themes of sexuality and the repression thereof were extremely popular in nineteenth century literature, as this was the period of romanticism. The site serves as a perfect setting as it is seen as a place where the past comes to life, encoded within the remains of the ancient town. Instead of focusing on the observation of nature as external to human experience, this movement emphasized the inner self. Pompeii then became a locale, situated in an ancient Golden Age, where the confines of rationality could be escaped and desires could be embraced.48 In Gautier’s Arria Marcella (1852) Octavien becomes enthralled by the imprint of Arria’s bosom exhibited in the Naples Museum, and after spending a illusory evening with her, is cast back into reality, permanently affected by his revelations in Pompeii. The ancient site is described as an evocative setting of past passions, taking precedence over lived human experience in the mind of the protagonist. The story interweaves fantasy with reality, dreaming with waking, and ultimately represents the need to repress desires in order to become part of society at large. Jensen similarly explores the connection between subconscious urges that emerge when one is confronted with artefacts from the past, and the means by which they are stifled. The main difference between the two stories is the fact that Norbert, Jensen’s hero, encounters symptoms of his repressed sexual desires and is ultimately able to resolve them by uncovering their actual meaning embodied within the artefacts of the past. The Pompeian woman Gradiva remains preserved through her likeness in a stone relief but is simultaneously inaccessible, much like Norbert’s desires and the past of Pompeii itself. Freud put these social and moral anxieties into theoretic framework with his concept of psychoanalysis. In his theory, Pompeii gains a new meaning as a locus for the concealment of traumatic events. In his eyes, the excavation of the site of Pompeii was a metaphor for the exploration of these anxieties, and thus by extension, the self.49 The conflation of the worlds of imagination and reality into a single image can be seen as the ‘stylization of desire and form of repression’.50 If connected with the concept of a cognitive landscape, Pompeii becomes a metaphor for the psyche, the layers of rubble burying the past through the process of repression. In Freud’s analysis of the novel Gradiva we can distinguish three ways to view Pompeii’s function as a repository for human experience.51 One of these is the physical ruins, the main source of our information. Another is the deceased population of Pompeii, still thought to communicate with the living, occupying the same space as the modern visitor. Finally there is the ephemeral impression that history leaves behind in its passing, a mere footprint, like that of Gradiva. This method of transference is the basis for the psychoanalytical treatment. We entomb an 47 Richardson in Hales & Paul 2011:317 Cunningham & Jardine 1990:4 49 Gardner Coates 2012:70 50 Armstrong 2005:20 51 Orrels in Hales & Paul 2011:185 48 6 embodiment of unresolved events into images through time. This simultaneously preserves the memory and renders it inaccessible. In order for the trauma to be laid to rest the experience must first be uncovered in its repressed form, only then can it be dislodged and brought to the surface.52 By making Norbert’s fantasy both beguile and cure him, Freud shows how external physical representations can reflect deeper psychic processes, but also serve as means to control them.53 Pompeii is often seen as a moment frozen in time.54 It is presented to the public through exhibits and artworks as a site that has remained unchanged since its original burial. This essay has shown the inaccuracy of this premise. Not only did Pompeii have a long history before the eruption but as this essay has proven perceptions of the site also carried on changing after its burial by Mount Vesuvius. Pompeii is what we would term a cognitive landscape, a site of remembrance that simultaneously shapes and is shaped by our own experiences. Images of Pompeii have become invested with the discourses that define our own world views, ever changing within the circumstances through which they are interpreted. They become framed within a long history of philosophical development, not evident in the time in which the entities themselves originated. These entities then present coherent images to the viewer, unquestioning of their hidden preconceptions. Trypanis writes that historic sites are appropriated by the living so that they can ‘sleep the life that went before’.55 This expresses the imaginative potential the site has as a juncture between our own time and that of the ancients, and the ease with which we become absorbed in the dream it has come to represent. Whether manifested in works of art, literature or scientific theories, our views of Pompeii show a dialectic relationship between historical truth and interpretation according to the psychological needs of the individual or community. In this sense the historical consciousness in the Pompeian anthology is constituted by what the senses perceive but also by what the imaginations and emotions create. 52 Pollock 2006:25 Freud Museum London http://www.freud.org.uk/exhibitions/10507/gradiva-the-cure-through-love/ [accessed 20/02/2013] 54 Binford 1981:196 55 Trypanis 1964:18 53 7 Illustrations Accessed between 21:32 and 22:48 on 28/4/2013 1. John Martin. The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum. 1822 Source: http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2011/sep/19/john-martin-pompeii-paintingrestored 2. Randolph Rogers. Nydia, the blind flower girl of Pompeii. 1956 Source: http://www.artrenewal.org/pages/artist.php?artistid=3916 3. Edward Poynter. Faithful unto death. 1865 Source: http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/walker/collections/19c/poynter.aspx 4. Tom Pfeiffer. Plaster Casts. Source: http://www.volcanodiscovery.com/photos/pompeji/image2.html 5. Allan McCollum. The Dog from Pompeii. 1991 Source: http://allanmccollum.net/allanmcnyc/anne_dagbert.html 6. Pan with a She-goat. Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum Source: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/9926420/Erotic-Pompeii-goat-statue-arrivesin-the-British-Museum.html 7. Gabi netto Secreto/Secret Cabinet. National Archaeological Museum of Naples Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/ell-r-brown/7604959416/ 8. Priapus Weighs his Large Phallus. House of the Vettii, Pompeii Source: http://www.pbase.com/doowopper/image/3076500 8 1. 2. 9 3. 4. 10 5. 6. 11 7. 8. 12 BIbliography Abramiuk, M. (2012) Foundations of Cognitive Archaeology, Massachusetts:MIT Press. Ancient Digger, ‘Pompeii: Erotic Art and Roman Sexuality’ on Ancient Digger Blog, 21/05/2012, accessed 21/04/2013 15:43. http://www.ancientdigger.com/2012/05/pompeii-erotic-art-and-roman-sexuality.html Armstrong, R.H. (2005) A Compulsion for Antiquity, London: Cornell University Press. Bartman, W.S. & Lawson, T. (1996) Allan McCollum, Los Angeles: A.R.T Press. BBC, ‘A point of View: Pompeii’s not-so ancient Roman Remains‘ on BBC News, 23/11/2012, accessed 21/04/2013 16:52. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-20407286 Beard, M. (2008) Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town, London: Profile Books LTD. Benvenuto, B. (1994) Concerning the Rites of Psychoanalysis, London: Routledge Bernfeld, S.C. (1951) ‘Freud and Archeology’ in American Imago: a Psychoanalytic Journal for the Arts and Sciences, Vol. 8, No. 2 (June), p.107-128. Bernstein, M. (2013) ‘Gradiva Medica: Freud's Model Female Analyst as Lizard-Slayer’ in American Imago, Vol. 60, No. 3, p.285-301. Binford, L.R. (1981) ‘Behavioral Archaeology and the “Pompeii Premise”’ in Journal of Anthropological Research, Vol. 37, No. 3 (Autumn), p.195-208. Breslin, R.B. (1992) ‘Digging for the Truth The Sigmund Freud Antiquities: Fragments of a Buried Past Review’ in The Threepenny Review, No. 49 (Spring), p.22-23. Burke, E. (1827) ‘A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful’ in The Works of the Right Honourable Edmund Burke, Vol. 1, London:C. & J. Rivington, p.67-262. Cunningham, A., & Jardine, N. (1990) Romanticism and the Sciences, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. De Caro, S. (2003) Le Cabinet Secret du Musée Archéologique National, Naples:Electa Napoli. Dwyer, E. (2007) ‘Science or morbid curiosity? the casts of Giuseppe Fiorelli and the last days of romantic Pompeii’ in Gardner Coates, V.C and Seydl, J.L. Antiquity Recovered: the legacy of Pompeii and Herculaneum, LA: J. Paul Getty Museum. 13 Dwyer, E. (2012) ‘Review of Pompeii in the Public Imagination, from Rediscovery to Today’ on Reviews in History, accessed 22/02/2013 10:35. http://www.history.ac.uk/reviews/review/1284 Dwyer, E. (2013) Pompeii’s Living Statues: Ancient Roman Lives Stolen from Death, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. Freud, S. (1987) ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’ in On Metapsychology, Middlesex: Penguin Books. Freud Museum London (2007) Gradiva Project: William Cobbing, London: Camden Arts Centre. Freud Museum London, ‘Gradiva: The Cure Through Love’ and ‘Freud and Archaeology’, accessed 20/02/2013 10:36. http://www.freud.org.uk/exhibitions/10507/gradiva-the-cure-through-love/ http://www.freud.org.uk/education/topic/40037/freud-and-archaeology-/ Gardner Coates, V.C. [et al.] (2012) The Last Days of Pompeii: Decadence, Apocalypse, Resurrection, Los Angeles, Getty Publications. Getty Museum, ‘The Last Days of Pompeii: Decadence, Apocalypse, Resurrection’ on Getty Museum Online 12/9/2012-7/1/2013., accessed 25/02/2013 15:26. http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/pompeii/ Grant, M. (1975) Erotic art in Pompeii: the secret collection of the National Museum of Naples, London: Octopus Books. Goldstein, L. (1979) ‘The impact of Pompeii on the literary imagination’ in Centennial Review, Vol. 23, p.227-241. Hake, S. (1993) ‘Saxa loquuntur: Freud’s Archaeology of the Text’ in Boundary 2, Vol. 20, No. 1, p.146173. Hales, S. & Paul, J. (2011) Pompeii in the public imagination from its rediscovery to today, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Harris, J. (2007), Pompeii Awakened: a story of rediscovery, London: I. B. Tauris. Horowitz, G.M. (2001) ‘Pompeii Beyond the Pleasure Principle: Death and Form in Freud’ in Sustaining loss: Art and Mournful Life, Stanford: Stanford University Press, p.91-132. Jensen, W. (2003) Gradiva & Freud, S. (2003) Delusions and Dream in Wilhelm Jensen’s Gradiva, Los Angeles: Green Integer. Kofman, S. (1988) The Childhood of Art: an interpretation of Freud’s aesthetics, New York: Columbia University Press. 14 Landlow, G.P. (2007) ‘Disaster as Punishment, the Religious Sublinme, and Pompeii’ on Victorian Web, accessed 25/02/2013 13:32. http://www.victorianweb.org/art/crisis/crisis1b.html Leggio, G. (2012) ‘Pompeii and the Historical Imagination’ in American Arts Quarterly, Vol. 29, No. 3. (Summer), accessed 24/04/2013 13:56. http://www.nccsc.net/essays/pompeii-and-historical-imagination Leppmann, W. (1966) ‘Arbaces’ Skull, Arria’s Bosom, Gradiva’s Foot’ in Pompeii in Fact and Fiction, London: Elek Books. Levin, Y. (2005) ‘Conrad, Freud, and Derrida on Pompeii: A paradigm of disappearance’ in Partial Answers: Journal of Literature and the History of Ideas, Vol. 3, No. 1, p.81-99. Ling, R. (2009) Pompeii: History, life and afterlife, Gloucestershire: The History Press. Nersessian, N.J. (1995) ‘Opening the Black Box: Cognitive Science and History of Science’ in Osiris: Constructing Knowledge in the History of Science, 2nd series, Vol. 10, p.194-211. Owens, J. ‘Ancient Roman Life Preserved in Pompeii’ on National Geographic, accessed 05/05/2013 21:32. http://science.nationalgeographic.co.uk/science/archaeology/pompeii/ Pollock, G. (2006) ‘The Image in Psychoanalysis and the Archaeological Metaphor’ in Psychoanalysis and the Image, Oxford: Blackwell, p.1-29. Renfrew, C. (1982) Towards an Archaeology of Mind, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Thomas, J. (2004) Archaeology and Modernity, London: Routledge. Trypanis, C.A. (1964) Pompeian Dog, New York: Chilmark Press. Varone, A. (2000) Eroticism in Pompeii, Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider. Webster, R. (1995) ‘Rediscovering the Unconscious’ in Why Freud was Wrong, London: The Orwell Press. 15