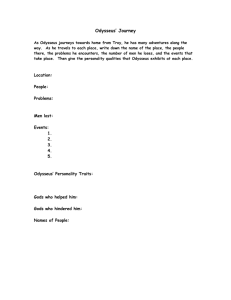

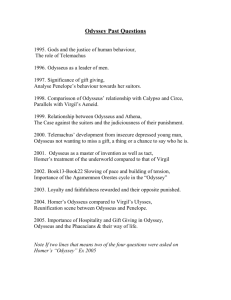

The Return of Odysseus

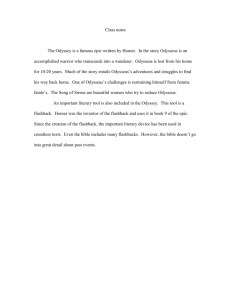

advertisement