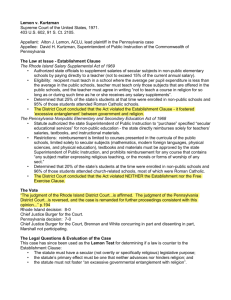

Allegheny County v. ACLU

advertisement