Force = Mass x Acceleration

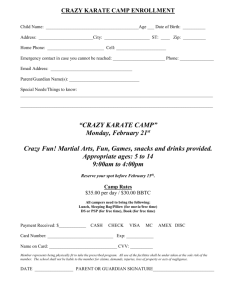

advertisement