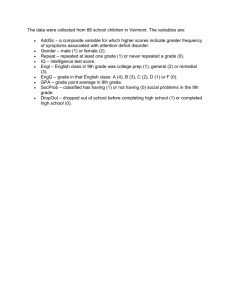

June 10, 2010

advertisement

THURSDAY, JUNE 10, 2010 5 Los Angeles Mis-firing for Misconduct By D. Gregory Valenza A client seeking advice about firing an employee who curses, throws things, or even makes threats of bodily harm expects a green light. A competent employment lawyer usually may oblige without significant risk. Usually. “Obey now, grieve later,” is a well-worn maxim of workplace law. But its edges have frayed as the law has evolved, primarily in the context of disability discrimination claims. D. Gregory Valenza is a partner with Shaw Valenza in the firm’s San Francisco office. He can be reached at gvalenza@shawvalenza.com or (415) 9835960. For example, Maria Menchaca worked as a student counselor for the Maricopa Community College District in Arizona. A 1991 automobile accident caused injury to her brain. Upon her return to work, the district provided her with several adjustments to her duties as a job coach. Years later, a student complained Menchaca shouted and spoke disrespectfully in class. She took leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act and later returned to work with significant restrictions. The district provided additional adjustments to her course load and responsibilities. ‘Obey now, grieve later,’ is a well-worn maxim of workplace law. But its edges have frayed as the law has evolved, primarily in the context of disability discrimination claims. In January 2006, Denise Bowman, the new Department Chair, met with Menchaca to discuss her responsibilities. Bowman reminded Menchaca she was supposed to work 35 hours per week, and had not done so the prior week. Hours after the meeting, Menchaca confronted Bowman, telling her that if she “reported Menchaca’s comings and goings to the administration,” Menchaca would “come back and kick [Bowman’s] ass.” Menchaca immediately told management she had a meltdown and was having trouble coping with job-related (and unrelated) stress. After consulting with her doctor, Menchaca took another leave of absence. Menchaca’s doctors later approved her return to work, but with restrictions limiting her contact with students. There were no open jobs to which Menchaca could transfer that matched her needs. The district therefore terminated her employment. Menchaca sued the district in federal court under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The district argued in a motion for summary judgment that its decision to discharge Menchaca was legitimate and nondiscriminatory. The district pointed out that Menchaca’s threat violated its violence policy and also constituted a crime in Arizona. No matter. The district ran into 9th Circuit caselaw, under which it is generally a violation of the ADA to discharge an employee for misconduct that arises out of a disability. For example, the 9th Circuit has held that if an employer discharges an employee for poor attendance caused by the employee’s obsessive-compulsive disorder, the employer is in effect discharging because of a disability rather than violation of its attendance rules. See Humphrey v. Mem’l Hosps. Ass’n, 239 F.3d 1128, 1139-40 (9th Cir. 2001). As the court explained: the hospital’s “stated reason for Humphrey’s termination was absenteeism and tardiness. For purposes of the ADA ...conduct resulting from a disability is considered to be part of the disability, rather than a separate basis for termination.” Humphrey did not involve employee misconduct. But the 9th Circuit extended its holding in Gambini v. Total Renal Care Inc., 486 F.3d 1087 (9th Cir. 2007). There, an employee with bi-polar disorder was discharged after she cursed, shouted, and threw papers at her supervisors during a meeting about her performance. Reversing a verdict in favor of the employer, the court held the jury should have been instructed: “Conduct resulting from the disability...is part of the disability and not a separate basis for termination.” Following Gambini, The district court in Menchaca v. Maricopa Cmty. College Dist., 595 F. Supp. 2d 1063 (D. Ariz. 2009), decided Menchaca’s conduct was part of her disability and, therefore, denied the district’s motion for summary judgment. The court opined that the facts of Menchaca’s case were similar to those presented in Gambini. The court declined to follow another 9th Circuit case, Newland v. Dalton, 81 F.3d 904 (9th Cir. 1995), which upheld termination of an employee who went on a drunken rampage. He claimed his conduct arose out of alcoholism. The district court in Menchaca held that her conduct, even if illegal, was not sufficiently “egregious” to fall within the Newland line of authority: “Menchaca’s statement that she would “kick [Bowman’s] ass” is plainly more akin to a profanity-laced outburst containing a veiled threat Gambini than to an attempt to fire an assault rifle at individuals in a bar.” The courts outside the 9th Circuit’s borders are less tolerant of violent conduct, even if attributable to a disability. For example, the 2nd Circuit in Sista v. CDC Ixis N. Am. Inc., 445 F.3d 161, 165 (2006), held that the employer’s decision to discharge the plaintiff because of his shouting and veiled threats was legitimate, even though the plaintiff claimed a mental disability caused the outbursts. More recently, a federal district court upheld the discharge of an employee claiming that his bi-polar disorder — the same disability claimed in Gambini — excused his misconduct. See Calandriello v. Tennessee Processing Center, 22 Am. Disabilities Cas. (BNA) 1153 (M.D. Tenn. 2009). Robert Calandriello viewed assault rifles and other violent content online at work. He altered and displayed a company poster by substituting a picture of Charles Manson for another image. His office computer contained photographs of an assault rifle in his home. Confronted about his conduct, he claimed bi-polar disorder affected his judgment. The employer fired him anyway. C alandriello sued under the Tennessee Human Rights Act, which courts interpret consistent with the ADA. Accepting Calandriello’s bi-polar disorder was a disability, the court agreed with Tennessee Processing Center that “[t]aking action because of fear of potential violence is a legitimate non-discriminatory reason for an adverse employment action.” The court in Calandriello relied on a 7th Circuit opinion, which concisely stated: “if an employer fires an employee because of the employee’s unacceptable behavior, the fact that that behavior was precipitated by a mental illness does not present an issue under the Americans with Disabilities Act.... The Act does not require an employer to retain a potentially violent employee.” See Palmer v. Circuit Court of Cook County, Ill., 117 F.3d 351, 352 (7th Cir. 1997). The 7th Circuit in Palmer therefore recognized what the courts in Menchaca and Gambini did not: to require an employer to overlook evidence of violent conduct “would place the employer on a razor’s edge — in jeopardy of violating the Act if it fired such an employee, yet in jeopardy of being deemed negligent if it retained him and he hurt someone.” California statutes and case law require employers to ensure a safe workplace, and to protect employees from violent co-workers. Employers in the 9th Circuit attempting to comply with the ADA face the Hobson’s choice of risking liability to third parties if an employee with a disability engages in actual “egregious, criminal” conduct, or risking liability to the employee for disability discrimination. The court in Gambini pointed out employers may challenge whether the employee is “qualified,” i.e., he or she can perform essential job functions with or without reasonable accommodation. Second, the court continued: “even if a plaintiff were to establish that she’s qualified, under the ADA the defendant would still be entitled to raise a ‘business necessity’ or ‘direct threat’ defense against the discrimination claim.... [Third,] [d]efendant may also raise the defense that the proposed reasonable accommodation poses an undue burden “ The court’s attempt to blunt its own holding is cold comfort for employers. “Undue burden,” “business necessity,” and “direct threat,” are notoriously difficult defenses for employers to prove. As to whether the plaintiff is a “qualified individual,” employers will be forced to argue that accommodating threats and the like are not “reasonable.” But the court in Gambini already suggested tolerance of a plaintiff’s misconduct indeed is a form of reasonable accommodation. For now, employers’ best hope may be that a California appellate court will refuse to follow Gambini. The 9th Circuit’s decision is not binding on California courts. Elliott v. Albright, 209 Cal. App. 3d 1028, 1034 (1989) (“Where the federal circuits are in conflict, the authority of the [9th] Circuit...is entitled to no greater weight than decisions from other circuits.”).But unless or until an appellate court in California expressly refuses to follow Gambini, employers have few satisfactory options for addressing employees’ potentially violent misconduct arising from known disabilities. Circuit Courts Split on Cross-Border Forum Selection Clauses By Edward Chang and Rhianna S. Bauer F orum selection clauses in the context of international commerce have become increasingly important in the 21st century. As U.S. and foreign economies continue to intertwine, such clauses allow domestic and foreign companies to bargain for the jurisdiction where potential disputes will be litigated in the event a business relationship sours. From a purely economic perspective, allowing parties to agree to a particular forum where lawsuits will be litigated allows companies to accurately account for the prospective sunk costs of litigation when dealing at arms-length. Indeed, the U.S. Supreme Court has established a longstanding policy of encouraging the enforcement of forum selection clauses, repeatedly holding that such clauses should be enforced absent a strong reason to set them aside. See, e.g., M/S Bremen v. Zapata Off-Shore Co., 407 U.S. 1 (1972). However, this domestic policy may run headlong into the policy of many foreign countries, which often give little to no weight to jurisdictional provisions in agreements that attempt to circumvent that country’s jurisdiction. Accordingly, courts at all levels have grappled with the potential implications on both international commerce and comity (the respect shown by one country for the laws of another) in deciding whether to enforce cross-border forum agreements. The Federal Circuit Courts are not immune. The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals decision in Applied Medical Distribution Corp. v. The Surgical Company BV, 587 F.3d 909 (9th Cir. 2009), illuminates this division, as its holding is directly contra to the 11th Circuit’s holding in Canon Latin America Inc. v. Lantech, 508 F.3d 597 (11th Cir.2007). The 9th Circuit has repeatedly held that requiring parties to litigate in the jurisdiction of their agreed-to forum is in accord with the longstanding policy of enforcing forum selection clauses. And, because no impact on comity is present when dealing with purely private non-governmental entities, the 9th Circuit has determined that equitable relief such as an antisuit injunction is entirely proper. See E. & J. Gallo Winery v. Andina Licores S.A., 446 F.3d 984 (9th Cir.2006). The 11th Circuit, on the other hand, has largely eviscerated the enforceability of such forum selection provisions in the international context, citing comity concerns and setting forth a nearly impossible to satisfy “identical claims” test that invites forum shopping. In Applied Medical, U.S. plaintiff Applied and Belgian defendant Surgi- cal Co. entered into a distribution agreement in 2005, whereby Surgical agreed to purchase surgical supply products from Applied for distribution in Europe. As part of the bargain, the parties agreed that both federal and state courts in California would have exclusive jurisdiction to “adjudicate any dispute arising out of [the] Agreement” and that California law governed the parties’ relationship. However, when a dispute arose in 2007 over the payment of certain “goodwill indemnities” in conjunction with the agreement’s termination, Surgical asserted that it was entitled to relief under a Belgian statute in a Belgian tribunal, arguing the obligation to pay those indemnities was outside the scope of the agreement’s jurisdictional clauses. Applied promptly filed a declaratory relief action in the Central District of California to enforce the parties’ forum selection agreement. Predictably, Surgical then filed suit in Belgium, seeking payment for its termination related damages under Belgian law. While awarding declaratory relief to Applied on summary judgment, the Central District, Judge David O. Carter presiding, ultimately declined to enjoin Surgical from pursuing its action in Belgium, finding that Surgical’s Belgian claims under Belgian law were “potentially broader” than the issues before the California court and therefore not encompassed by the parties’ choice of law and forum selection provisions. Applied appealed that decision based on the 9th Circuit’s decision just three years earlier in E&J Gallo Winery v. Andina Licores SA, 446 F.3d 984 (9th Cir. 2006) (holding it unnecessary for the claims presented in both actions to be identical for an antisuit injunction to issue and that no impact on comity would result,) a case both factually and legally identical to Applied Medical. On appeal, the 9th Circuit overturned the District Court, granting Applied’s request for an antisuit injunction in accordance with Gallo. In reaching its decision in Applied Medical, the 9th Circuit considered three factors: whether the parties and the issues in both actions were the same; whether the foreign action would frustrate a policy of the forum issuing the injunction; and whether the impact on comity would be tolerable. In focusing on the first (and most contested) factor, the court concluded that the issues needed only to be “functionally the same,” not that the claims had to be “identical.” The court explained that this functional similarity arose when all of the issues “fall under the forum selection clause and can be resolved in the local action.” Neither the issues nor the claims needed to be precisely identical, because, as the court noted, requiring as much would be “counterproductive” and lead to “unintended results.” Curiously, this is precisely the holding in Canon. In Canon, the 11th Circuit held that the actual legal claims, not just issues, had to be identical in both actions in order for an antisuit injunction to issue. Taking a diametrically opposed view to that of the 9th Circuit, the 11th Circuit overturned the district court’s grant of an antisuit injunction, holding that because Lantech’s Costa Rican action hinged on statutory rights unique to Costa Rica, it could not be resolved by a judgment in a Florida district court. The 11th Circuit refused to give effect to the parties’ bargained-for jurisdictional clauses despite the choice of law provision (and corollary forum selection provision) in the parties’ agreement selecting Florida law and a Florida forum for “any litigation between the parties” because those Costa Rican statutory rights did not arise out of the agreement. The import of these conflicting decisions is clear: Applied Medical and Gallo have provided domestic businesses contractually agreeing to a forum in the 9th Circuit with certainty and reliability in the cross-border jurisdictional clauses negotiated with international entities. Canon, however, has established a standard of comparing competing lawsuits that rewards gamesmanship and pleading contrivance. Under its standard, an antisuit injunction is only appropriate if the claims (not the issues) brought in both forums are identical (not functionally the same). Thus, a later-filing party may simply plead claims outside the scope of the parties’ agreement (such as under a foreign statute) different from the first-filed lawsuit, in a forum with laws more favorable to it at the time a particular dispute arises, and circumvent the parties’ forum selection provision. Surprisingly, the U.S. Supreme Court has yet to consider the issue, denying certiorari in the Canon case in June 2008. Moreover, further review was not sought in the recent decision in Applied Medical. However, on such a fundamental question of contractual interpretation and enforcement in the context of international commerce, it is only a matter of time before the Circuits’ opposing views will need to be reconciled for the sake of uniformity. Edward S. Chang is a trial practice associate at Jones Day and practices in all aspects of complex commercial litigation. He can be reached at echang@jonesday.com. Rhianna S. Bauer is a trial practice associate at Jones Day. She can be reached at rsbauer@jonesday.com.