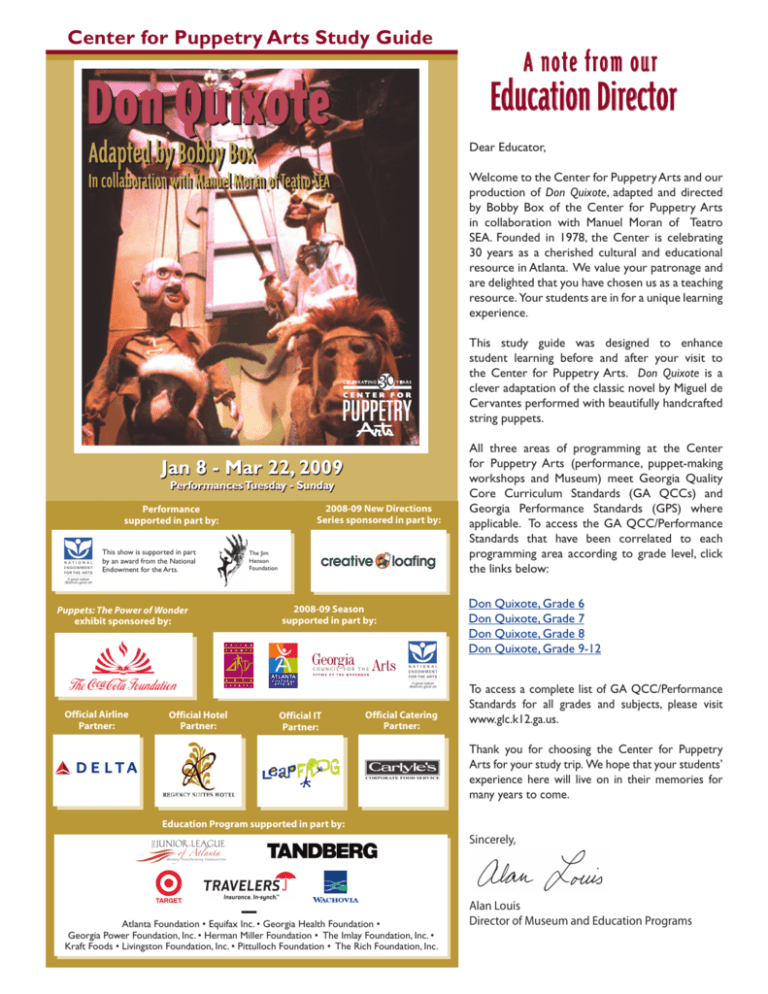

Center for Puppetry Arts Study Guide

A note from our

Education Director

Dear Educator,

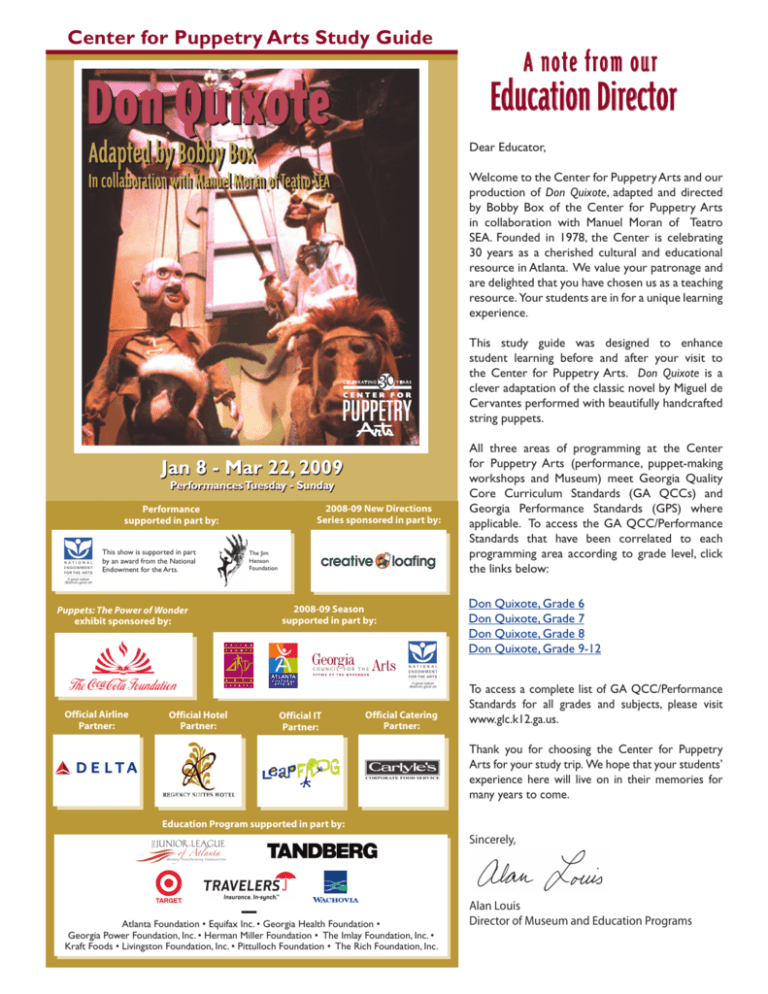

Welcome to the Center for Puppetry Arts and our

production of Don Quixote, adapted and directed

by Bobby Box of the Center for Puppetry Arts

in collaboration with Manuel Moran of Teatro

SEA. Founded in 1978, the Center is celebrating

30 years as a cherished cultural and educational

resource in Atlanta. We value your patronage and

are delighted that you have chosen us as a teaching

resource. Your students are in for a unique learning

experience.

This study guide was designed to enhance

student learning before and after your visit to

the Center for Puppetry Arts. Don Quixote is a

clever adaptation of the classic novel by Miguel de

Cervantes performed with beautifully handcrafted

string puppets.

Jan 8 - Mar 22, 2009

Performances Tuesday - Sunday

2008-09 New Directions

Series sponsored in part by:

Performance

supported in part by:

This show is supported in part

by an award from the National

Endowment for the Arts.

Puppets: The Power of Wonder

exhibit sponsored by:

Official Airline

Partner:

Official Hotel

Partner:

The Jim

Henson

Foundation

2008-09 Season

supported in part by:

Official IT

Partner:

Official Catering

Partner:

All three areas of programming at the Center

for Puppetry Arts (performance, puppet-making

workshops and Museum) meet Georgia Quality

Core Curriculum Standards (GA QCCs) and

Georgia Performance Standards (GPS) where

applicable. To access the GA QCC/Performance

Standards that have been correlated to each

programming area according to grade level, click

the links below:

Don Quixote, Grade 6

Don Quixote, Grade 7

Don Quixote, Grade 8

Don Quixote, Grade 9-12

To access a complete list of GA QCC/Performance

Standards for all grades and subjects, please visit

www.glc.k12.ga.us.

Thank you for choosing the Center for Puppetry

Arts for your study trip. We hope that your students’

experience here will live on in their memories for

many years to come.

Education Program supported in part by:

Sincerely,

Atlanta Foundation • Equifax Inc. • Georgia Health Foundation •

Georgia Power Foundation, Inc. • Herman Miller Foundation • The Imlay Foundation, Inc. •

Kraft Foods • Livingston Foundation, Inc. • Pittulloch Foundation • The Rich Foundation, Inc.

Alan Louis

Director of Museum and Education Programs

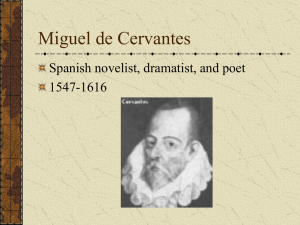

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra is considered to be one of the greatest figures

in Spanish and world literature. He was born in Alcala de Henares, a Spanish

province of Madrid on September 29, 1547 – the same year as William Shakespeare.

He was the fourth of seven children. His father was an itinerant surgeon, who

struggled to maintain his practice by traveling the length and breadth of Spain.

Little is known about his early life, but in 1569 Cervantes traveled to Italy to

serve in the household of an Italian nobleman, and he joined the Spanish army a

year later. He fought bravely against the Turks at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571,

where he received serious wounds and lost the use of his left hand. After a

lengthy period of recovery and further military duty, he departed Italy for Spain

in 1575, only to be captured during the return journey by Barbary pirates. He

was taken to Algiers and imprisoned for five years until Trinitarian friars paid a

considerable sum of money for his ransom. This experience was a turning point

in his life, and numerous references to the themes of freedom and captivity

later appeared in his work. Upon returning to Madrid, Cervantes married and

worked a variety of odd jobs. He often got into trouble over illegal seizures

of property and was sent to jail. In 1585 he published his first work in prose,

La Galatea, a pastoral romance which had attracted qualified praise from some

of his contemporaries. He was also writing for the theater, and at this time he

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra

began to write short stories, some of which were later included in his Exemplary

There is no authentic portrait of Cervantes.

Tales. His most famous work, Don Quixote de la Mancha, was published in two

This is an artist’s conception of what he

parts in Madrid. Part I appeared in 1605; the second part in 1615. The novel was

might have looked like.

an immediate success. The first part went through six editions the year of its

publication, and was soon translated into English and French. Although written as a satirical romance, it contained fiction’s first “fun”

characters, Don Quixote and his old horse Rosinante, whose bumbling exploits were not only read and re-read by a delighted public

but inspired innumerable imitations. Cervantes died in Madrid on April 22, 1616. William Shakespeare died the same day. Cervantes

was buried in a Trinitarian monastery a few blocks from his house, but the specific location of his tomb is unknown.

SYNOPSIS

Our story takes place in sixteenth century Spain, when an elderly gentleman named Don Quijano has apparently gone mad from

reading too many books on chivalry. Proclaiming himself a knight, he sets out with his obedient squire, Sancho Panza, to reform the

world and revive the age of chivalry, choosing a woman of loose morals to be his noble lady Dulcinea. This lighthearted comedy

presents an alternate reality that unfolds into a hysterical tale of enchantment and madness. Don Quixote mistakes inns for castles, a

play about chivalry for the real thing, flocks of sheep for armies, wine casks for monsters, and windmills for giants. Fantasy and Reality

collide as windmills, giants, armies and monsters take center stage in this fantastic tale of a man who searches for nobility and finds,

instead, himself.

STYLE OF PUPPETRY

Don Quixote is performed with puppets fashioned after traditional Sicilian rod marionettes from Italy. These characters are puppets on

strings but include a metal rod that serves as a direct control to the puppet’s head. The puppeteers in this show wear period costumes

and remain in full view of the audience throughout the show. The puppeteers provide all of the characters’ voices live. Each puppeteer

wears a cordless microphone to amplify her/his voice. A musician provides Spanish guitar accompaniment on stage throughout

the performance.

© 2009 Center for Puppetry Arts. All Rights Reserved.

2

BIBLIOGRAPHY

•

Amorós, Pilar and Paco Parico. Títeres Y Titiriteros: El lenguaje de los Títeres. Mira Editores, 2000.

• Bell, John. Strings, Hands, Shadows: A Modern Puppet History. The Detroit Institute of Arts, 2000.

• Burton, David G. Anthology of Medieval Spanish Prose (Cervantes & Co. Spanish Classics) (Spanish Edition).

Juan de la Cuesta, 2005.

• Calderon de la Barca, Pedro. La Vida Es Sueno / Life is a Dream (Cervantes & Co. Spanish Classics)

(Spanish Edition). European Masterpieces, 2006.

• Cascardi, Anthony J. The Cambridge Companion to Cervantes (Cambridge Companions to Literature).

Cambridge University Press, 2002.

• Cervantes, Miguel de. Don Quijote de la Mancha (Clasicos Inolvidables). Edimat Libros, 2007.

• Chandler, Richard E. and Kessel Schwartz. A New History of Spanish Literature. Louisiana State

University Press, 1991.

• Dore, Gustave. Dore’s Illustration for Don Quixote: A Selection of 190 Illustrations by Gustave Dore.

Dover Publications, Inc., 1990.

• Flores, Angel. Nine Centuries of Spanish Literature : Nueve siglos de literatura española :

A Dual-Language Anthology. Dover Publications 1998.

• Fong, Kuang-Yu and Stephen Kaplin. Theatre on a Tabletop: Puppetry for Small Spaces.

New Plays Incorporated, 2003.

• Gasset, Angeles. Títeres con Cabeza. Aguliar, 1967.

• Gies, David Thatcher. Theatre and Politics in Nineteenth-Century Spain : Juan De Grimaldi As Impresario

and Agent (Cambridge Iberian and Latin American Studies). Cambridge University Press, 1988.

• Keller, Daniel S. Historical Notes on Spanish Puppetry. (Unknown Binding) 1959.

• Kidd, Michael. Stages of Desire: The Mythological Tradition in Classical and Contemporary Spanish Theater.

Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995.

• Lorca, Federico Garcia. Four Puppet Plays: Play Without a Title, The Divan Poems and Other Poems,

Prose Poems, and Dramatic Pieces. Sheep Meadow, 1990.

• McCrory, Donald P. No Ordinary Man: The Life and Times of Miguel de Cervantes. Dover Publications, 2006.

• Neruda, Pablo (Donald D. Walsh, translator). Spain in Our Hearts/Espana en el corazon

(New Directions Bibelots). New Directions (Bilingual Edition), 2005.

• Resnick, Seymour and Jeanne Pasmantier. Nine Centuries of Spanish Literature : Nueve siglos de literatura

española : A Dual-Language Anthology. Dover Publications, 1994.

• Serrano, Juan and Susan Serrano, eds. Nine Centuries of Spanish Literature : Nueve siglos de literatura

española: A Dual-Language Anthology. Hippocrene Books, 1995.

© 2009 Center for Puppetry Arts. All Rights Reserved.

3

INTERNET RESOURCES

http://www.h-net.org/~cervantes/csapage.htm

Visit the Cervantes Society of America, founded to advance the study of the life and works of Miguel

de Cervantes.

http://cervantes.tamu.edu/V2/CPI/index.html

Visit the website for the Cervantes Project.

http://www.online-literature.com/cervantes/

Explore The Literature Network’s Cervantes site.

http://quixote.mse.jhu.edu/index.html

Investigate a digital exhibit of translations and illustrations of Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra’s novel

Don Quixote de la Mancha.

http://www.puppetbooks.co.uk/

Search this site for out of print and hard to find puppetry books.

http://www.titiriteros.com

Explore the website of Los Tititeros de Binéfar, a puppet company from Spain.

http://www.sea-ny.org/SEA_ArtsInEducation.html

Visit the website of the Society of the Educational Arts, Inc. (SEA), a Bilingual Arts-in-Education

Organization & Latino Theatre Company for Young Audiences dedicated to the empowerment

and educational advancement of children and young adults. SEA creates educational theater and

arts programs specifically designed to examine, challenge and create possible solutions for current

educational and social issues affecting our communities.

Scene from Don Quixote

© 2009 Center for Puppetry Arts. All Rights Reserved.

4

LEARNING ACTIVITIES

6th Grade: Tilting at Windmills: Uncovering the Origins of

Common Expressions

Georgia Performance Standards covered: Grade 6, ELA6R1 a, b, c, (for informational texts),

ELA6RC3 a, b, c, ELA6RC4 a, b, c, ELA6LSV1 c.

Objective: Students will reference an online database of common expressions to determine their

origins. Students will record their findings on a worksheet.

Materials: Computers with Internet access, worksheets from this study guide, and pens or pencils.

Procedure:

1. Have students go to http://users.tinyonline.co.uk/gswithenbank/sayindex.htm

2. Distribute worksheets. Ask students to use the online database to look up each of the 10

expressions listed on the worksheet and read what each one means and where it came from.

3. Ask students to match the corresponding expression to its origin by placing the number of the expression from the first column in the blank in front of the description in the second column.

4. Answers in “Origins” column from top to bottom: 5, 7, 9, 2, 10, 4, 1, 6, 3, 8.

Evaluation: Discuss the expressions, their meanings and their origins with students. Review

worksheets for completeness and correct answers.

Puppets from Don Quixote

© 2009 Center for Puppetry Arts. All Rights Reserved.

5

Name________________________________________________________

Date____________________

Tilting at Windmills: Uncovering the Origins of Common Expressions

Directions: Go to http://users.tinyonline.co.uk/gswithenbank/sayindex.htm. Look up each expression listed on

this sheet and read where it comes from. Then match each expression to its origin. Write the number of the expression

in the blank next to its origin.

Expression

1. get down to brass tacks

Origins

_____ This expression is actually

a misquotation from

Shakespeare’s King John.

2. Grand Pooh-Bah

_____ This expression comes from

Don Quixote de La Mancha

by Miguel Cervantes.

3. spin doctor

4. save for a rainy day

5. guild the lily

_____ This expression is named for a

Norse warrior renowned for his

fury in fighting.

_____ This expression comes from a

character in Gilbert and

Sullivan’s The Mikado.

6. don’t look a gift-horse in the mouth

_____ This expression comes from the

game of golf.

7. tilt at windmills

8. a wolf in sheep’s clothing

_____ This expression comes from the

days when most people were

farmers relying on good

weather for their survival.

9. go berserk

_____ This expression comes from a

technique used by textile

merchants to measure lengths of

fabric and negotiate a price.

10. par for the course

_____ This expression is related to the

length of a certain animal’s teeth.

_____ This expression comes from a

type of pitch in a baseball game.

_____ This expression comes from one of

Aesop’s Fables.

© 2009 Center for Puppetry Arts. All Rights Reserved.

6

LEARNING ACTIVITIES

7th Grade: Chivalry Today: Seven Knightly Virtues

Georgia Performance Standards covered: Grade 7, English/Language Arts, Reading and Literature,

ELA7R1 (for informational texts) a, b, c, d, e, f; ELA7R2 a, b, c, d.

Objective: Students will visit a website to define the seven knightly virtues identified by

http://www.chivalrytoday.com.

Materials: Computers with Internet access, worksheets from this study guide, and pens or pencils.

Procedure:

1. Discuss the meaning of chivalry and virtues with students. How do these ideas relate to the

story of Don Quixote?

2. Distribute worksheets to students.

3. Have students go to http://www.chivalrytoday.com/.

4. Ask students to read the content on the page titled “Seven Knightly Virtues” and then fill in the

definitions of each virtue in the space provided on the worksheet.

Assessment: Collect student worksheets and check for completeness and reading comprehension.

Scene from Don Quixote

© 2009 Center for Puppetry Arts. All Rights Reserved.

7

Name____________________________________________________

Date_____________________

The Seven Knightly Virtues

Directions: Go to http://www.chivalry.today.com/. Look up the meaning of each of the

terms and give the definition in the space provided.

1. Courage –

2. Justice –

3. Mercy –

4. Generosity –

5. Faith –

6. Nobility –

7. Hope –

© 2009 Center for Puppetry Arts. All Rights Reserved.

8

Name______ANSWER KEY______________________

Date_____________________

The Seven Knightly Virtues

Directions: Go to http://www.chivalry.today.com/. Look up the meaning of each of the

terms and give the definition in the space provided.

1.

Courage - More than bravado or bluster, today’s knight in shining armor must have

the courage of the heart necessary to undertake tasks which are difficult, tedious or

unglamorous, and to graciously accept the sacrifices involved.

2.

Justice - A knight in shining armor holds him — or herself — to the highest standard

of behavior, and knows that “fudging” on the little rules weakens the fabric of society for

everyone.

3.

Mercy - Words and attitudes can be painful weapons in the modern world, which is why

a knight in shining armor exercises mercy in his or her dealings with others, creating a

sense of peace and community, rather than engendering hostility and antagonism.

4.

Generosity - Sharing what’s valuable in life means not just giving away material goods,

but also time, attention, wisdom and energy — the things that create a strong, rich and

diverse community.

5.

Faith - In the code of chivalry, “faith” means trust and integrity, and a knight in shining

armor is always faithful to his or her promises, no matter how big or small they may be.

6.

Nobility - Although this word is sometimes confused with “entitlement” or

“snobbishness,” in the code of chivalry it conveys the importance of upholding one’s

convictions at all times, especially when no one else is watching.

7.

Hope - More than just a safety net in times of tragedy, hope is present every day in

a modern knight’s positive outlook and cheerful demeanor — the shining armor that

shields him or her and inspires people all around.

© 2009 Center for Puppetry Arts. All Rights Reserved.

9

LEARNING ACTIVITIES

8th Grade: Write a Film Review of Man of La Mancha (1972)

GA QCC Standards covered: Grade 8, Language Arts (Writing): 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70; (Listening):

15. Georgia Performance Standards covered: Grade 8, English/Language Arts (Writing): ELA8W1,

ELA8W2.

Objective: Students will read Don Quixote de la Mancha, watch the 1972 film Man of La Mancha and

write a review comparing the film adaptation to the book.

Materials: Video tape or DVD of Man of La Mancha (1972) directed by Arthur Hiller, sample reviews of

films from newspapers or magazines, and computers with word processing software or pen and paper.

Procedure:

1. Give students copies of sample film reviews written by critics for newspapers or magazines.

Discuss the content of the reviews. What does a reader expect in a film review? Is a review

simply a retelling of the film’s storyline? Make a list of aspects of a film that are addressed in

a review such as: effectiveness of storytelling (Is it true to the source? Did anything not make

sense or seem hard to believe?), conveying of emotion, quality of acting (Are the characters

believable?), look and feel of the film, effectiveness of music used in the film, authenticity of the

film (Do the sets and props reflect the time period when the story is supposed to place?), etc.

2. After students have read the sample reviews, have them read the book Don Quixote de la Mancha,

and then show them the 1972 film Man of La Mancha.

3. Ask students to write a review of the film, taking into account the era in which the film was made (early 1970s). Students can look up specific production details, a complete cast list,

etc. for Man of La Mancha on the Internet. (www.IMDB.com)

Assessment: Ask students to share their reviews in class. Ask them to rate each other’s reviews based

on the criteria that were established when reading the sample reviews.

© 2009 Center for Puppetry Arts. All Rights Reserved.

10

LEARNING ACTIVITIES

9th-12th Grades: Idealism – A Double-Edged Sword?

GA QCC Standards covered: Grades 9-12, Language Arts, Advanced Composition (Writing/Usage/

Grammar): 29, 30, 31, 32. Georgia Performance Standards covered: Grade 9, English/Language

Arts (Reading and Literature): ELA9RL4; (Writing): ELA9W1, ELA9W2; Grade 10, English/Language Arts

(Reading and Literature): ELA10RL4; (Writing): ELA10W1, ELA10W2; Grade 11, English/Language Arts

(Writing): ELA11W1, ELA11W2; Grade 12, English/Language Arts (Writing): ELA12W1, ELA12W2.

Objective: Students will write a poem, newspaper article, story, play/dialogue, research paper or essay

to answer the question: When should idealism be tempered?

Materials: Computers with word processing software and printers.

Procedure:

1. Discuss with your students the meaning of idealism. Idealism is holding on to a set of beliefs

which are a rigid system of the way life is “supposed to be” or “should be.” How can idealism be

a positive force in a person’s life?

2. Next, discuss the possible negative aspects of being too idealistic:

a. The belief system you have adopted about how things “should be done’’ often gets challenged by the way things are in reality.

b. You could become distracted by a fantasy or dream of how your life should be which often interferes with your accepting the “here and now’’ realities of life. You may

become out of touch with reality or too “pie in the sky.”

c. You may experience disappointment about others not accepting or living up to

your ideals.

d. You might become very disillusioned, depressed or despondent and therefore despair over how imperfect life is at home, school, work, or in the community.

e. You may experience a lowering of your self-esteem because you are not capable of living

up to your ideals.

f. You may be so blinded by your “shining’’ ideals that you forget others are free to have their own opinions.

3. Ask students to write an essay, poem or short story on the theme of idealism. Have them

brainstorm ideas, write a first draft, revise their paper and finally produce a final product.

Assessment: Collect student writing for Language Arts portfolios. Review work for clarity and

relevance to the assigned theme.

Center for Puppetry Arts is a non-profit, 501(c)(3) organization and is supported in part by contributions from corporations,

foundations, government agencies, and individuals. Major funding for the Center is provided by the Fulton County Board of Commissioners under the

guidance of the Fulton County Arts Council. Major support is provided by the City of Atlanta Office of Cultural Affairs. These programs are

supported in part by the Georgia Council for the Arts (GCA) through the appropriations from the Georgia General Assembly. GCA is a Partner

Agency of the National Endowment for the Arts.The Center is a participant in the New Generations Program, funded by the Doris Duke Charitable

Foundation/The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and administered by Theatre Communications Group (TCG), the national organization for the

American Theatre. The Center is a Member of TCG and the Atlanta Coalition of Performing Arts. The Center also serves as headquarters of

UNIMA-USA, the American branch of Union Internationale de la Marionnette, the international puppetry organization.

11

Study Guide Feedback Form

The following questions are intended for teachers and group leaders

who make use of the Center for Puppetry Arts’ study guides.

1. In what grade are your students?

2. Which show did you see? When?

3. Was this your first time at the Center?

4. Was this the first time you used a Center Study Guide?

5. Did you download/use the guide before or after your field trip?

6. Did you find the bibliography useful? If so, how?

7. Did you find the list of online resources useful? If so, how?

8. Did you reproduce the grade-appropriate activity sheet for your class?

9. Additional information and/or comments:

Please fax back to the Center for Puppetry Arts at 404.873.9907.

Your feedback will help us to better meet your needs. Thank you for your help!

1404 Spring Street, NW at 18th • Atlanta, Georgia USA 30309-2820

Ticket Sales: 404.873.3391 • Administrative: 404.873.3089 • www.puppet.org • info@puppet.org

Headquarters of UNIMA-USA • Member of Atlanta Coalition of Performing Arts and Theatre Communications Group

Text by Alan Louis • Design by Melissa Sims • © Center for Puppetry Arts Education Department, January 2009.