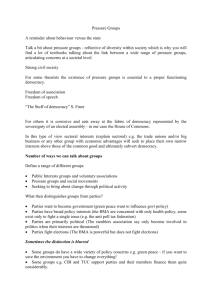

Neo-Pluralism: A Class Analysis of Pluralism I and Pluralism II

advertisement