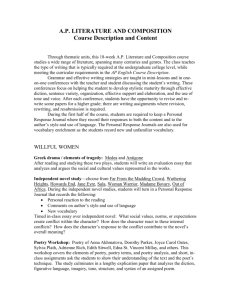

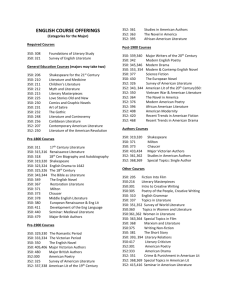

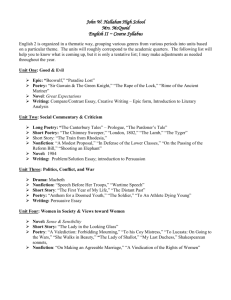

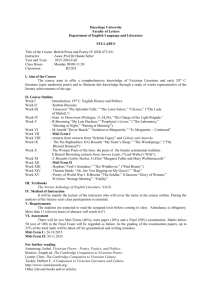

AP Literature and Composition

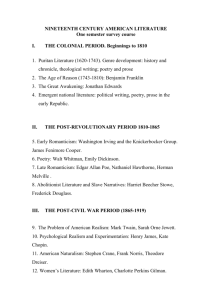

advertisement