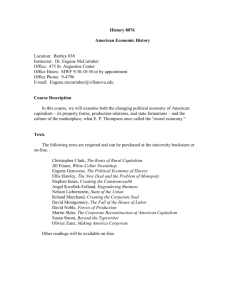

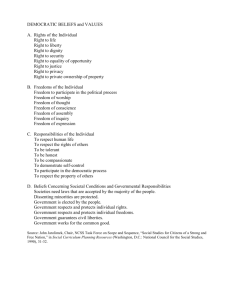

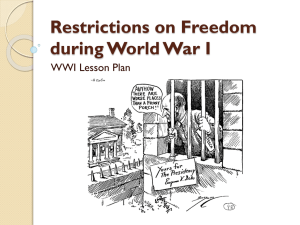

Freedom, Democracy and Economic Welfare

advertisement