1 Lessons from the Past. Shackleton's Way: Leadership Lessons

advertisement

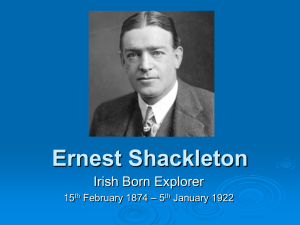

1 Lessons from the Past. Shackleton’s Way: Leadership Lessons from the Great Antarctic Explorer. Margot Morrell and Stephanie Capparell, Viking Penguin Publishing, 2001. “He has been called ‘The greatest leader that ever came on God’s earth, bar none.’” This is the opening line to Shackleton’s Way: Leadership Lessons from the Great Antarctic Explorer, by Margot Morrell and Stephanie Capparell, a very enjoyable discussion of leadership lessons told through the story of Ernest Shackleton’s life and especially his attempt to cross the Antarctic continent on foot. The book does a good job of keeping the story of Shackleton’s journey the focus of the discussion, bringing up the leadership lessons at obvious points without unnecessarily interrupting the flow of the narrative or making the lessons feel contrived. It also includes sections showing how modern leaders have effectively used lessons learned from Shackleton to improve their own leadership. The story of Ernest Shackleton’s journey to Antarctica in 1914-1916 is almost too fantastic to be believed. Shackleton and twenty-seven crew left South Georgia Island on December 5, 1914 on board the Endurance. The plan was to sail through the Weddell Sea to the Antarctic coast where most of the team would disembark. Some would stay on the coast making scientific observations, while Shackleton and four others would attempt to cross the Antarctic continent on foot, meeting up with another ship sent to wait for them. Unfortunately the sea ice never left the Weddell Sea that summer, and the Endurance became trapped in ice on January 18, 1914, just one day’s sail from their intended landing spot. They remained in the ship, drifting northwest with the ice all through the winter, until early spring when the ice began shifting, crushing the ship on October 27, 1915. For the next five months the men lived in five tents on the ice, nearly 200 miles from the nearest land and over 1000 miles from the nearest humans. Unable to drag their supplies across the ice, they were forced to wait for the drifting ice to take them to sea. On April 9, 1916 the ice finally gave away around them, and they took to three small lifeboats salvaged from the wreck of the Endurance. After a week on the sea in the lifeboats, the men finally reached Elephant Island, an uninhabited rock with no vegetation and no shelter. The crew had spent over 16 months on the ice without touching land. But they were not safe, as there was no way to live on Elephant Island and no hope of rescue from the 2 isolated spot. So Shackleton and five men set off in one of the lifeboats and sailed 800 miles across the South Atlantic Ocean in 18 days, finally landing back on South Georgia Island. However, they were still not safe, because they landed on the opposite side of the island from the only settlement. So Shackleton and two men walked 30 miles across the unmapped interior of the island, crossing mountain ranges, glaciers and waterfalls, till they finally reached a whaling station 36 hours later. After rescuing the men left on the opposite side of the island, Shackleton set about rescuing the men remaining on Elephant Island. It took four attempts over five months to reach the island, but eventually the men were rescued on September 3, 1916. Despite all the difficulties not a man was lost, and several recounted that the experience was one of the best times of their lives. While the story itself is incredible, what makes this a remarkable lesson on leadership is that to a man, the crew gave sole credit to Shackleton for not only their survival, but for making the endeavor an enjoyable time. Shackleton not only managed the vision and the details of the expedition, but ably managed the personalities and morale of the crew for the entire time. Even as they watched their ship sink beneath the ice, the crew trusted their leader and never lost hope. “We were in a mess, and the Boss was the man who could get us out. It is a measure of his leadership that this seemed almost axiomatic,” (p. 133) wrote R.W. James, the physicist on board. Shackleton’s leadership style was described as “the antithesis of the old command-and-control models. His brand of leadership instead values flexibility, teamwork, and individual triumph” (p. 10). Some lessons one can draw from Shackleton’s strategies include surrounding yourself with cheerful, optimistic people; picking a No. 2 who is loyal and but not a yes-man; and hiring people who share your vision. Through these strategies Shackleton was able to maintain an upbeat, positive environment even in the worst situations. And at critical times, when a negative voice could do serious damage, Shackleton kept the few pessimistic individuals close to him, to lessen their effect on the other men. The book is full of practical applications like these. But the larger leadership lessons are the ones I found to be most useful. Shackleton was a bold visionary. Even though his expeditions never fully succeeded at their intended missions, he built on the failures to develop even more grand plans. Yet while he was a visionary, Shackleton was meticulous in detail. He planned for every contingency, and when events forced his plans to change, his new plans were just as meticulous, not seat-of-the-pants. The ability to think at both the visionary level and the detail 3 level was a large part of what made Shackleton great. Another part of his greatness was his ability to focus on the real goal. Shackleton had nearly died as a part of Robert Scott’s first unsuccessful attempt to reach the South Pole, and had seen what happened when a leader focused more on the goal than on the people he was leading. This focus eventually led to Scott’s death; Shackleton learned that no matter the organizational goal, the overriding goal must always be the lives and the safety of those he led. Shackleton’s perspective led him to make the welfare of his people his utmost priority, and his men loved him for it. Even after the awful struggles of his Endurance expedition, eight men from that crew signed up to go with Shackleton to Antarctica again four years later. Shackleton’s goal was not just the mission of the expedition, but was to ensure and improve the welfare of the men he led. This is the great leadership lesson from Ernest Shackleton. As the authors put it, “Leadership, after all, is more than just reaching a goal. It is about spurring others to achieve big things, and giving them the tools and the confidence to continue achieving” (p. 210). I would love to meet Ernest Shackleton, to hear his stories of Antarctica. And I would love to hear his insights into leadership, to hear him expand on ideas mentioned in the book. I would ask him how he was able to keep both the details and the big picture in his head at the same time, and which he relied on more. I would ask him how he was able to keep up his optimism, even in the face of disaster. Did he have a way of going off in private and venting his feelings? Was there a person on the crew who could serve as an absolute confidant? There is no evidence for such a person, but then how did Shackleton contain his feelings within himself? And finally, I would ask him how he was able to manage his doubts. He couldn’t confide in anyone on his crew, but surely he had doubts about their survival. How did he work through them, how did he keep them from rising to the surface and impacting his leadership? For two years he never weakened, he never broke down or cracked in his optimism and drive for survival and success. Learning how that was possible would be a wonderful insight. I thought that Shackleton’s Way was one of the best leadership books I’ve read. The story is so compelling that the reader wants to continue reading, and the authors had the good sense not to distract from the story with long discourses about leadership. Instead they made concise points at opportune moments, and let the story provide the discussion and illustration of the leadership lesson. The organization of the book into chapters that both moved the story along and highlighted broad leadership lessons was very effective without being overwhelming. At the end of each chapter was a summary of the leadership lessons and a case study of a modern 4 leader who used them, so the points made in the main text were reinforced. This book would be an outstanding addition to the bibliography of resources, especially for people new to leadership studies. The book does an outstanding job of illustrating not just specific ideas for how to lead, but also the importance of leadership to achieving a goal. Ernest Shackleton was an ideal subject for a book on leadership, a person who “failed only at the improbable; he succeeded at the unimaginable” (p. 1).