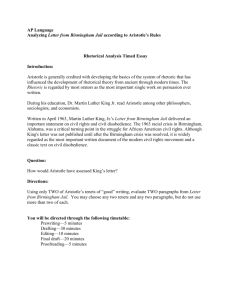

Base Macro

advertisement