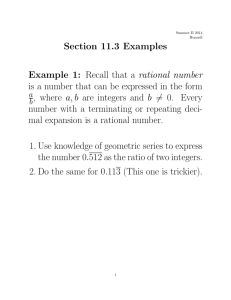

Investigating Rational Equations

advertisement

Chapter 8

Investigating Rational Equations

Suppose that you started a business selling picnic tables and wanted to determine

the cost of each table you made. Part of your cost is for materials and is proportional

to the number of picnic tables made. Other costs, such as renting space or

equipment, are constant regardless ofthe number of tables you sell. Because the

cost per picnic table is this total cost divided by the number of tables, the

independent variable will appear in both the numerator and the denominator. What

do you think this graph will look like?

The similar bone structure in the forelimbs of whale and humans indicates a

common ancestor. The similar streamlined body shape of a shark and a dolphin,

however, does not. What types of evidence can we use to learn about evolution and

the relationships among species?

During This Chapter

• You will identify characteristics of the rational

parent function.

• You will graph and solve equations with

variables in denominators.

• You will apply rational functions to real-world

situations.

Application

Canceling factors in rational expressions sets the

foundation for skills used when working with rational

functions. Rational functions model inverse variation

relationships, such as those seen in acoustics and

aerodynamics.

Section 8.1

Inverse Variation

Objectives

• Set up equations involving inverse variation

relationships

• Solve problems involving inverse variation

using cross multiplication

New Vocabulary

• Inverse variation

• Vary inversely

Suppose that you ordered a certain amount of pizza for a party. If more people showed up for the party than you had expected, then each person

would get less pizza than you had planned. The more people there were, the less pizza each person would get. If you had planned on each

person getting three slices, and double the expected number of guests arrived, then how much pizza would there be for each person?

8.1 - Inverse Variation

Inverse Linear Variation

Direct variation describes a relationship between two unknowns whose quotient is a constant. When

two variables are said to exhibit direct variation, the absolute values of those two variables increase or

decrease together. If one variable triples, the other triples also. If one is cut in half, the other is cut in half

as well. This type of relation can be expressed by the equation y = kx, where k is the proportionality

constant. If the proportionality constant for an equation is not given, any two values that vary directly

y

can be substituted into the equation y = kx and solved for k. Thus, k is equal to the proportion . Figure

x

1

8.1-1 shows a graph of the relation y = x, which is one example of direct variation.

2

Jump to Direct Linear Variation

Because the equation y = kx takes the form of a linear function, a relation exhibiting direct variation is

linear. This is confirmed by inspecting the graph shown in Figure 8.1-1. Furthermore, comparing the

general equation y = kx to the slope-intercept form y = mx + b shows that the slope of the graph is the

proportionality constant (k) and that the graph passes through the origin.

Figure 8.1-1 The relation y =

Jump to Slope-Intercept Form

direct variation.

1

x is an example of 2

Inverse variation describes a relationship in which the product of the two variables is a nonzero

constant. One example of a function exhibiting inverse variation is shown in Table 8.1-1. For each pair

of x- and y-coordinates, the product xy is exactly 30.

x

3

4

5

6

7.5

10

y

10

7.5

6

5

4

3

Table 8.1-1 The values of x and y in this table demonstrate inverse variation.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

451

Section continues

8.1 - Inverse Variation

Properties of Inverse Variation

Examining the values in Table 8.1-1 shows that when one variable increases, the other decreases. This

behavior is a fundamental characteristic of inverse variation. The product xy must be constant.

Therefore, an increase in x must be compensated for by a decrease in y whenever k > 0. If x is multiplied

by a certain factor, then y must be divided by that same factor. It also may be noted that this relation is

its own inverse relation, which means that swapping the variables x and y does not change the relation.

This property can be seen in the table. For example, both (3,10) and (10,3) are solutions of the equation

because in both cases, the two coordinates multiply to 30.

Jump to Inverses Algebraically

Certain properties of inverse variation can be seen more readily with a graph. Figure 8.1-2 presents a

graph of the relation shown in Table 8.1-1, where the product of any xy-pair is exactly 30. Although the

slope of this graph is not constant, it is always negative because any increase in x must be accompanied

by a decrease in y. Very large values of x correspond to very small values of y. However, the graph will

never reach the x-axis, where y = 0, because no value of x can be multiplied by 0 to produce 30. Only a

positive value of y could be multiplied by any positive x to produce a solution. As a result, as the graph

continues to the right, it constantly approaches the x-axis but never crosses or even touches it.

In the same way, the graph of the inverse variation relation does not touch or cross the y-axis. Values of

30

x very close to 0 will correspond to very large y-values. For example, in the relation y =

, when

x

1

, y = 3000 because these values multiply to 30. However, no y-value can correspond to x = 0, so

x=

100

the graph never reaches the y-axis.

Figure 8.1-2 As the graph of the inverse variation

relation extends to the right, it continually approaches,

but never touches, the x-axis.

x

3

4

5

6

7.5

10

y

10

7.5

6

5

4

3

Table 8.1-1 The values of x and y in this table demonstrate inverse variation.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

452

Section continues

8.1 - Inverse Variation

Formulating Inverse Variation Equations

In some problems, the presence of inverse variation is stated explicitly. For example, a problem might

say that a driver’s speed and the time taken to reach her destination vary inversely. If two quantities

vary inversely, then their product is a nonzero constant. A verbal description might also state that these

quantities vary indirectly or that they are inversely proportional.

Inverse variation may exist without being stated explicitly. For example, a problem might describe a job

that a certain number of people can accomplish in a certain amount of time. Although the problem may

not state that the number of people and the time required

are inversely proportional, reasoning shows that more

workers will accomplish the job in less time. Specifically,

the number of people multiplied by the number of hours

each works is equal to the total number of man-hours

needed to complete the job. Thus, as the number of people

increases, the amount of time each works decreases so that

their product remains a constant. For example, Figure

8.1-3 shows several people working together to dig a

ditch. The more people there are to work, the less time the

job will take. This type of relation is an example of inverse

variation.

Figure 8.1-3 The amount of time the job takes varies inversely with the number of workers.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

453

Section continues

8.1 - Inverse Variation

Constant of Proportionality

If two variables vary inversely, their product is always a nonzero constant. As a result, any inverse

variation between variables x and y can be represented by the equation xy = k, where k is a nonzero

1

k

. This

constant. Solving for one of the variables puts this equation into the form y = , or y = k

(x)

x

resembles the form of an equation describing direct variation, but it can now be seen that one variable

varies directly with the reciprocal of the other variable.

Jump to Direct Linear Variation

The constant of proportionality (k) can be found for any relation exhibiting inverse variation as long as a

single pair of corresponding values are known, as shown in Figure 8.1-4. For example, suppose that

variables a and b vary inversely, and it is known that a = 4 when b = 10. The proportionality constant

can readily be found by substituting the known values into the equation ab = k. In this case,

4 ⋅ 10 = 40 = k. This constant can then be used in order to solve for other values in the relation with the

40

equation ab = 40, or b =

.

a

Figure 8.1-4 The constant of

proportionality can be found for any

inverse variation relation as long as a

single pair of corresponding values are

known.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

454

Section continues

8.1 - Inverse Variation

Example problem" "

The number of balloons that each child at a party receives varies inversely with the number "

"

"

"

of children attending the party. Write an equation to represent this relation in order to solve "

"

"

"

for the number of balloons.

Analyze"

"

"

The problem describes an inverse variation between two quantities and asks for an equation "

"

"

representing the relation.

"

Formulate" "

"

Choose letters as variables to represent the number of children and the number of balloons. Use "

"

"

"

the definition of inverse variation to relate the variables with an equation, and then solve the "

"

"

"

equation for the number of balloons.

Determine" "

"

Let b = the number of balloons"

"

"

Choose letters to represent the variable "

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

quantities.

"

"

"

"

Let c = the number of children

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

bc = k""

k

b = ""

c

Justify"

"

"

Meaningful letters were chosen to represent the two quantities. An equation was then written "

"

"

"

corresponding to the definition of inverse variation xy = k, which states that multiplying the two "

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

variables produces a constant product. Solving for the number of balloons produces the equation k

b= .

c

Evaluate"

"

"

Producing the equation was straightforward, using only the definition of inverse variation. The "

"

"

"

answer is reasonable because more children attending the party would result in fewer balloons for "

"

"

"

each child.

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

Apply the definition of inverse variation.

"

"

"

"

"

"

Solve for b.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

455

Section continues

8.1 - Inverse Variation

Solving Inverse Variation Equations

Suppose that the variables c and d vary inversely. If the proportionality constant is known, then the

value of d can be found for any corresponding value of c. For example, if k = 36 and c = 4, then d can be

calculated by solving the inverse variation relationship cd = k for the unknown variable d, producing

k

36

d = . Substituting the known values of k and c into the equation results in the solution d =

= 9. In

c

4

this way, the value corresponding to any known variable value can be determined as long as the

proportionality constant is known.

If the proportionality constant is not known, solutions to an inverse variation relation can be found as

long as a corresponding pair of values is provided. This is done by substituting the pair of values into

the equation and determining k, as seen in Figure 8.1-5. Once k is known, the corresponding value to

any given value of one of the variables can be calculated.

For example, suppose it takes 3 h for four men to assemble a device. The principle of inverse variation

can be used in order to determine how long it would take for six men to assemble the same device.

Substituting the known corresponding values for the number of workers (w) and the time required (t)

into the equation wt = k results in the constant of proportionality (k). In this problem, k =

(4 men)(3 h) = 12 man-hours. The inverse variation equation can be used again, but this time solved for

12

. Substituting in the known values results in the unknown quantity, t =

w

12 man-hours

= 2 h. Thus, six men are needed to assemble the device in 2 h.

t=

6 men

Figure 8.1-5 Once the constant of

proportionality is known, the

corresponding value to any x or y other

than 0 can be calculated.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

456

Section continues

8.1 - Inverse Variation

Example problem" "

If y varies inversely with x, and y = 4 when x = 6, what is y when x = 12?

Analyze"

"

"

The problem presents an inverse variation relationship and gives one solution of the equation, the "

"

"

point (6,4). The problem also asks for the y-value that corresponds to x = 12.

Formulate" "

"

Substitute the coordinates of the given point into the inverse variation equation xy = k, and "

"

"

"

calculate the proportionality constant. Then, substitute both the value of k and the second given

"

"

"

"

x-value into the inverse variation equation, and calculate the corresponding value of y.

Determine" "

"

xy = k

"

"

"

"

6 ⋅ 4 = k"

"

"

Plug in known x- and y-values.

"

"

"

"

24 = k""

"

"

Solve for k.

"

"

"

"

xy = k

"

"

"

"

12y = 24"

"

"

Plug in known x- and k-values.

"

"

"

"

y = 2" "

"

"

Solve for y.

Justify"

"

"

Both pairs of x- and y-values must satisfy the equation xy = k, and k must have the same value for "

"

"

"

any coordinate pair in this relation. Therefore, the known pair was used to determine the value of "

"

"

"

k, and this constant was then used to determine that y = 2 when x = 12.

Evaluate"

"

"

The equation describing inverse variation provided a straightforward way to solve for the "

"

"

"

unknown quantities. The answer is reasonable because the product of 6 and 4 is equal to the "

"

"

"

product of 12 and 2.

"

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

457

Section continues

8.1 - Inverse Variation

Example problem" "

The cost per person for a charter bus ride is inversely proportional to the number of people who "

"

"

"

ride. If 40 people ride, then the cost is $20 per person. What is the cost per person if only 25 people "

"

"

"

ride?

Analyze"

"

"

The problem presents a scenario involving inverse variation between the number of people on a "

"

"

"

bus (n) and the cost per person (c). It gives one pair of corresponding values for number and cost, "

"

"

"

and it asks for the cost corresponding to a different number of people.

Formulate" "

"

Write an equation relating the cost per person (c) to the number of people (n). Then, substitute the "

"

"

"

known values into the inverse variation equation nc = k, and calculate the proportionality "

"

"

"

constant (k). Finally, substitute both the value of k and the second given n-value into the inverse "

"

"

"

variation equation, and calculate the corresponding value of c.

Determine" "

"

nc = k

"

"

"

"

40 ⋅ 20 = k" "

"

Plug in known values of n and c.

"

"

"

"

800 = k"

"

"

Solve for k.

"

"

"

"

nc = k

"

"

"

"

25 ⋅ c = 800" "

"

Plug in known values of n and k.

"

"

"

"

c = 32""

"

Solve for c.

Justify"

"

"

Both pairs of n- and c-values satisfy the equation nc = k, and k has the same value for both "

"

"

"

coordinate pairs in this relation. Therefore, the known pair was used to determine the value of k, "

"

"

"

and this constant was then used to determine that the ride costs $32 per person for 25 people.

"

Evaluate"

"

"

The equation describing inverse variation provided a straightforward way to solve for the "

"

"

"

unknown quantities. The answer is reasonable because the product of 40 and 20 is equal to the "

"

"

"

product of 25 and 32.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

458

Section continues

8.1 - Inverse Variation

Other Inverse Variations

Inverse variation can occur with nonlinear factors as well. If x2 varies inversely with y, then

the inverse variation equation is x2 y = k instead of xy = k. For example, suppose that an

object is illuminated by a lamp. The greater the distance between the lamp and the object,

the less brightly the object is illuminated. However, the intensity (brightness) of the light

does not vary inversely with the distance. Rather, it varies inversely with the square of the

distance, as illustrated by Figure 8.1-6. This relationship can be represented as Id2 = k, or

k

I = 2 , where I is the intensity in watts (W) per square meter, and d is the distance in meters.

d

Suppose that a certain lamp illuminates an object 0.5 m away with an intensity of 20 W/m2.

The relationship Id2 = k can be used in order to determine the lamp’s intensity at a distance

of 2 m. The method used to solve this problem is similar to the method for solving problems

involving simple inverse variation. The only difference is that here, one variable must be

squared before the inverse variation is applied. The first step is to calculate the value of k,

Figure 8.1-6 The intensity of a light source varies inversely

with the square of the distance.

using the known values for distance and intensity. This results in k = (20 W/m2 )(0.5 m)2 = 5 W. Next, this constant can be used in order to determine the

5 W

2

= 1.25 W/m .

intensity at 2 m. This gives the answer I =

2 m2

Most graphs of inverse variation relations share certain things in common with the graph of y =

k

.

x

5

. The graph has the same general shape as the basic

x2

graph in Figure 8.1-2, and it approaches both axes but never crosses either. However, the shape of the

Figure 8.1-7 shows a graph of the relation y =

graph is slightly different, and because it approaches the x-axis more quickly than the y-axis, it is not

symmetrical around the line y = x.

5

still

x2

has the basic characteristics of the

graph of an inverse variation relation.

Figure 8.1-7 The graph of y =

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

459

Section continues

8.1 - Inverse Variation

Example problem" "

"

"

"

"

If d varies inversely with the cube root of h, and d = 10 when h = 8, then what is h when d = 2?

Analyze"

"

"

The problem presents a relation in which the variable d varies inversely with the cube root of the "

"

"

"

variable h. This can be modeled by the equation d h = k. The problem gives a known pair of "

"

"

"

values for d and h, and then it asks for the value of h corresponding to a second d-value.

Formulate" "

"

"

"

"

"

Use the known pair of values and the inverse variation equation d h = k to determine the 3

constant (k). Then, use the equation d h = k and the known values of k and d to calculate the "

"

"

"

unknown value of h.

Determine" "

"

d h=k

"

"

"

"

10 8 = k"

"

"

Plug in known values.

"

"

"

"

20 = k""

"

"

Solve for k.

"

"

"

"

d h=k

"

"

"

"

2 h = 20"

"

"

Plug in known values.

"

"

"

"

h = 10"

"

"

Solve for

"

"

"

"

h = 1000"

"

"

Solve for h.

Justify"

"

"

Because the problem explicitly stated the inverse variation relationship, that relationship was "

"

"

"

represented as the equation d h = k. The proportionality constant could then be found and used "

"

"

"

to determine that h = 2000 when d = 2 .

"

"

The equation describing inverse variation provided a straightforward way to solve for the Evaluate"

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

h by cubing each side.

3

"

"

"

"

unknown quantities. The answer is reasonable because a decrease in d produced an increase in h "

"

"

"

and because a large change in h is required in order for its cube root to make a smaller change.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

460

Section complete

Section 8.2

The Rational Parent Function

Objectives

• Determine the characteristics of the rational

parent function

• Perform transformations on the rational

parent function

• Describe horizontal and vertical asymptotes

in a mathematical context

New Vocabulary

• Asymptote

• Odd (function)

Figure 8.1 The Rational Parent Function

The graphs of inverse relationships, or rational functions, are considered hyperbolic, a type of shape seen in human engineering in many different

forms. In this shape, the function approaches from far away, comes close to a focal point, and then sweeps away from that point. In architecture,

these shapes are often called saddles, such as the Scotiabank Saddledome in Calgary. Mathematicians sometimes bend the Cartesian plane into

a hyperbolic shape in order to explore different aspects of geometry. On the surface of a saddle, for instance, triangles can be drawn that have an

internal angle sum of less than 180°. What other structures or objects have you seen with this shape?

8.2 - The Rational Parent Function

Rational Characteristics

Rational numbers, or fractions, are numbers that are defined as the quotient of one integer by another.

In algebra, there are functions that are expressed as ratios of two polynomials. The rational parent

1

function, f(x) = , describes an inverse relationship between the input and the output. In Table 8.2-1, a

x

few values for the inputs and outputs of the rational parent function are given as an example. As the

absolute value of the input gets larger, the output approaches 0. Conversely, as the input approaches 0,

the output becomes larger.

The domain of the rational parent function contains an important exception because division by 0 is

undefined. The input cannot be 0, a condition that can be written in interval notation as (−∞, 0) ∪ (0, ∞)

or in set notation as D: {x x ≠ 0}. If the input of the rational parent function is 0, then the output is

undefined because the function would involve division by 0. Similarly, for the range of the rational

1

parent function, there is no value so large that = 0; therefore, (−∞, 0) ∪ (0, ∞) and R: {y y ≠ 0} hold.

x

Input

Output

–3

–1/3

–1/2

–2

1/8

8

1

1

5

1/5

Table 8.2-1 The rational parent

function always returns the inverse of

what it is given.

Jump to Rational & Irrational Numbers

Jump to Set Notation

The rational parent function is symmetrical in three ways, with line symmetry across y = x and y = − x

and rotational symmetry about the origin. Because the rational parent function is symmetrical about

y = x, it is its own inverse, meaning that if the x- and y-axes were switched, the graph would remain

the same. The rational parent function is illustrated in Figure 8.2-1 along with the lines of symmetry.

Figure 8.2-1 The rational parent function is symmetric

across two lines and about the origin.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

462

Section continues

8.2 - The Rational Parent Function

Asymptotes of the Rational Parent Function

The rational parent function approaches but never reaches 0. A function that approaches but does not

reach a specific value is said to have asymptotic behavior. An asymptote is the line that a function gets

closer to as it approaches a specific value in its domain where the function is undefined.

As the input of the rational parent function approaches infinity, the output approaches 0. Because

infinity is not a real number that can be used as an input for the function, the asymptote is the

horizontal line y = 0, or the x-axis. Thus, the x-axis is a horizontal asymptote of the rational parent

function. As the input of the function approaches 0, the y-values approach infinity, going to negative

infinity where x < 0 and positive infinity where x > 0. Again, the rational parent function is undefined

at x = 0, so the y-axis is a vertical asymptote. This behavior is described in Table 8.2-2 using decimal

notation.

A function is odd if making the input negative has the same effect as making the output negative.

Algebraically, a function is odd if f(−x) = − f(x). The graph of an odd function is symmetrical with

respect to the origin, having rotational symmetry at 180°. The linear parent function and the cubic

parent function are also examples of odd functions.

Input increasing toward infinity

Input approaching 0

x

y

x

y

10

0.1

0.1

10

20

0.05

0.05

20

1000

0.001

0.001

1000

10,000

0.0001

0.0001

10,000

1,000,000

0.000001

0.000001

1,000,000

Table 8.2-2 This function approaches 0 or infinity but cannot reach that value because it is

undefined. Note that x and y for one example are inverted in the other.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

463

Section continues

8.2 - The Rational Parent Function

Rational Transformations

Just as with other parent functions, the rational parent function can be transformed into other related

functions in its family, in this case, the rational function family. Different transforms are produced by

changing the value of different constants (parameters) in the transformation equation

y = a(f(b(x − c))) + d. For the rational parent function, the transformation equation takes the form

a

y=

+ d.

b(x − c)

Jump to Function Transformations

Vertical & Horizontal Dilations of the Rational Parent Function

The first parameter, a, controls vertical dilations and vertical reflections. Negative values of a reflect the

graph across the horizontal axis, in the vertical direction. Values of a close to 0 vertically compress the

graph, pulling all of the points toward the x-axis. Values of a greater than 1 vertically stretch the

Figure 8.2-2 This graph shows some

examples of vertical dilations and

reflections of the rational parent

function.

graph, pushing all of the points away from the x-axis. The effects of changing the parameter a are

illustrated in Figure 8.2-2. A value of 1 represents no transformation by the parameter a.

The next parameter, b, controls horizontal dilations and horizontal reflections. Negative values of b

reflect the graph across the vertical axis, in the horizontal direction. Values of b close to 0 horizontally

stretch the graph, pulling all of the points away from the y-axis. Values of b greater than 1

horizontally compress the graph, pulling all of the points toward the y-axis. The effects of changing the

parameter b are illustrated in Figure 8.2-3. A value of 1 represents no transformation by the parameter b.

Note that there is a relationship between the a and b parameters in the transformation equation of the

rational parent function.

Figure 8.2-3 This graph shows some

examples of horizontal dilations and

reflections of the rational parent

function.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

464

Section continues

8.2 - The Rational Parent Function

Vertical & Horizontal Translations of the Rational Parent Function

In the next transformation, the input is modified, f(x − c). For the rational parent function, this translates

(shifts) the graph to the right or left along the x-axis and changes the domain such that x ≠ c. In other

words, the vertical asymptote of the rational parent function is shifted to the position x = c, thus

changing the domain of the graph. A value of 0 represents no transformation by the parameter c.

The final transformation is on the output, f(x) + d. In this case, the graph shifts up and down along the

y-axis, shifting the range of the function to y ≠ d. Similar to the horizontal translation, this shifts the

horizontal asymptote to y = d. A value of 0 represents no transformation by the parameter d. Figure

8.2-4 shows some examples of horizontal and vertical translations of the rational parent function.

Figure 8.2-4 This graph shows some examples of

horizontal and vertical translations of the rational parent

function.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

465

Section continues

Virtual Manipulative - Rational Transformations

The rational parent function can be transformed in several ways, depending on how the parameters are

adjusted. The following virtual manipulative will allow you to translate, dilate, and reflect the rational

parent function across a coordinate plane.

You should have been able to compare the effects of different parameter changes on the rational parent

function. You should have noticed some subtle differences between the parameter changes that produce

horizontal and vertical transformations.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

466

Section continues

8.2 - The Rational Parent Function

Rational Inverse Function

One special characteristic of the rational parent function is that its inverse function is the same as

the function itself. Just as the x- and y-axes could be switched, the same could be done with the

1

1

output and input. That is, if y = , then the inverse function is defined by x = , which can be

x

y

1

solved for y to produce y = . This can be the case because the domain and range of the rational

x

parent function are equivalent sets, x ≠ 0 for the domain and y ≠ 0 for the range. Swapping the

domain and the range does not change what is in the sets for the rational parent function. The

linear parent function is also its own inverse.

To illustrate this graphically, if the points of the equation are graphed from 0.1 to 1, then the

inverse of this graph will look the same as graphing from x = 1 to 10, as shown in Figure 8.2-5.

This is also evident if values of the rational parent function are tabulated. In Table 8.2-3, a series of

inputs produce a series of outputs on the left. On the right, those outputs are used as inputs and

return the original numbers.

Figure 8.2-5 The rational parent function is its own

inverse.

Because the rational parent function is invertible, a graph of this function must pass both the

vertical line test and the horizontal line test. With the vertical line test, all lines passing through

points where x > 0 are in quadrant I, and where x < 0 are in quadrant III, with no points

overlapping. This confirms that the rational

parent function is indeed a function. For the

horizontal line test, a line passing through all

points on the y-axis passes through a point on

the graph only once. This can also be

confirmed by the fact that the rational inverse

function passes the vertical line test.

x

f(x) = 1/x

f(x)

x

f(x) = 1/x

f(x)

1

1/1

1

1

1/1

1

10

1/10

0.1

0.1

1/0.1

10

100

1/100

0.01

0.01

1/0.01

100

1000

1/1000

0.001

0.001

1/0.001

1000

Table 8.2-3 The invertible behavior of the rational parent function means that the output and input can be

reversed and the function remains true.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

467

Section complete

Section 8.3

Asymptotes

Objectives

• Investigate and identify horizontal and vertical

asymptotes

New Vocabulary

• Infinite discontinuity

• Point discontinuity

Throughout history, many fortresses with long and tall walls were built around cities in order to keep out intruders. People who wanted to enter the

cities would have to approach these walls and search for a way through. Asymptotes are like invisible barriers that functions approach and usually

cannot pass through. What other types of things can be approached but not easily passed through?

8.3 - Asymptotes

Vertical Asymptotes & Domain

A vertical asymptote is a line parallel to the y-axis that a function approaches but never crosses. A

vertical asymptote acts as an impenetrable wall to the graph of a function. As the graph of a rational

function approaches a vertical asymptote from either direction, the y-values either increase or decrease

without bound. A function and its vertical asymptote at x = 2 are shown in Figure 8.3-1.

Jump to Characteristics

Jump to Rational Characteristics

A vertical asymptote is a type of domain

restriction. A rational function is undefined

at a vertical asymptote, which is why the

graph does not cross it. Thus, for the graph

in Figure 8.3-1, there is a domain restriction

at x = 2, which means x can be any value

other than 2. The domain is expressed as

D: {x x ≠ 2}.

Infinite discontinuity occurs when a function

approaches positive or negative infinity

from either side of an asymptote, as shown

in Figure 8.3-2.

Figure 8.3-1 The y-values approach negative infinity as

the x-values approach 2 from the left, and positive

infinity as the x-values approach 2 from the right.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

469

Figure 8.3-2 The function has infinite discontinuity at x = 0 because the y-values approach infinity from the

right side, and negative infinity from the left side.

Section continues

8.3 - Asymptotes

Factoring the Denominator to Determine Restrictions & Asymptotes

A rational function can be reduced to lowest terms, which means all common factors in the numerator

and denominator are canceled out. A reduced rational function has a vertical asymptote at every value

of x that makes the denominator equal 0. A function can have many vertical asymptotes. For example,

1

has two vertical asymptotes. Setting the denominator equal to 0 and then factoring

g(x) =

2

x + 3x + 2

results in (x + 2)(x + 1) = 0, which yields the values x = − 1, − 2. Thus, there is a restriction in the

domain at these values because division by 0 is undefined. A restriction in the domain of a function in

lowest terms implies that there is a vertical asymptote at the same values, as shown in Figure 8.3-3.

Point of Discontinuity

A point discontinuity, also known as a hole, occurs when a common factor is present in both the

numerator and denominator of a rational function. A function is not continuous at this specific point

and is indicated by an open circle on the graph. A point discontinuity does not change the shape of the

graph and does not create an asymptote.

Figure 8.3-3 The x-values –2 and –1 are

domain restrictions as well as vertical

asymptotes in the graph of the function

1

g(x) = 2

.

x + 3x + 2

x+1

, and it has a point

x2 + 3x + 2

discontinuity at x = − 1. When the denominator of f(x) is factored, a common factor of (x + 1) is seen in

For example, the graph shown in Figure 8.3-4 is the function f(x) =

both the numerator and denominator. This factor simplifies to 1, and the function simplifies to

(x + 1)

1

f(x) =

=

, x ≠ − 1, x ≠ − 2. A hole is located on the graph because a common factor

(x + 1)(x + 2)

(x + 2)

of (x + 1) is found in both the numerator and denominator. Substituting the x-value into the function

results in the point (–1,1), which can be seen as the hole in the graph of f(x) in Figure 8.3-4.

Figure 8.3-4 An open circle is used

to represent the point discontinuity on

the graph of the simplified rational

function.

Chapter 3 - Investigating Rational Equations

470

Section continues

8.3 - Asymptotes

Example problem" "

Given the rational function f(x) =

Analyze"

x2 + 5x + 6

, identify and classify any discontinuities in the graph.

x2 + x − 2

"

"

The problem says to identify and classify any discontinuities in the graph.

Formulate" "

"

First, factor both the numerator and denominator to identify any domain restrictions and cancel out any common factors, if they "

"

"

exist. Set each remaining factor in the denominator equal to 0, and solve to find the vertical asymptotes of the function.

Determine" "

"

f(x) =

(x + 3)(x + 2)

"

(x − 1)(x + 2)

"

"

Factor both the numerator and denominator.

"

"

"

"

f(x) =

(x + 3)(x + 2)

"

(x − 1)(x + 2)

"

"

There is a common factor of (x + 2), which means there is a hole at x = − 2 .

"

"

"

"

f(−2) =

"

"

To find the location of the point discontinuity, substitute x = − 2 into the simplified function "

"

"

"

"

"

to find the y-value.

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

f(x) =

"

"

"

The simplified function has the factor (x − 1) remaining in the denominator, resulting in a "

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

vertical asymptote at x = 1 .

Justify"

"

"

1

will form The function has point discontinuity at x = − 2 and infinite discontinuity at x = 1. This means that the point −2, −

(

3)

"

"

"

"

a hole in the graph of the function, and there is a vertical asymptote at x = 1. This can be verified by graphing the original function "

"

"

"

on a graphing device.

Evaluate"

"

"

The method used was straightforward and a quick way to identify and classify the types of discontinuities in the function. The "

"

"

"

solution is reasonable because the graph of the simplified rational function has an infinite discontinuity at x = 1 and a point "

"

"

"

discontinuity at x = − 2. The original rational function is undefined at these two x-values.

"

1

−2 + 3

=

"

−2 − 1

−3

"

"

"

"

1

f(−2) = −

3

(x + 3)

"

(x − 1)

"

"

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

471

Section continues

8.3 - Asymptotes

Horizontal Asymptotes & Range

A horizontal asymptote is a line parallel to the x-axis that a function approaches and that in some cases

can be crossed, unlike vertical asymptotes. The equation for a horizontal asymptote is y = k, where k is a

real number.

End behavior describes the graph of a function as x approaches ± ∞. For example, the function

2x − 1

, as shown in Figure 8.3-5, has a horizontal asymptote at y = 2. As x approaches ± ∞, y

f(x) =

x

approaches 2. Horizontal asymptotes describe the end behavior of a function, indicating the y-value of the function as x approaches ± ∞. They also often act as a restriction on the range of a

function. Thus, in Figure 8.3-5, the range of the function is R: (−∞, 2) ∪ (2, ∞).

Many cases exist in which horizontal asymptotes can be crossed. For example, the function

x

g(x) =

graphed in Figure 8.3-6 approaches y = 0 as x approaches ± ∞ . There is a horizontal

2

x +2

asymptote at y = 0, yet the function crosses the asymptote at the point (0,0). Other functions oscillate

Figure 8.3-5 This function has a

horizontal asymptote at y = 2 and a

vertical asymptote at x = 0.

between the sides of the horizontal asymptote as they approach. Horizontal asymptotes describe end

behavior, not the behavior of the function on the interior.

Comparing the degree of the leading terms in both the numerator and denominator determines

whether there is a horizontal asymptote. If the degree of the numerator and denominator are the same,

then the horizontal asymptote is found by finding the ratio of the coefficients of the leading terms:

y=

leading coefficient of the numerator

leading coefficient of the denominator

If the degree of the denominator is greater than the degree of the numerator, like it is in the function

x−2

, then the asymptote is at y = 0. Conversely, if the degree of the numerator is greater than the

y=

x3

x2

degree of the denominator, like it is in the function y =

, then there is no horizontal asymptote.

(x − 1)

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

472

Figure 8.3-6 Horizontal asymptotes

can be crossed and are primarily

used to describe the end behavior of

a function.

Section continues

8.3 - Asymptotes

"

"

"

"

x2 + 2x + 1

, determine whether x3 + 8

there is a horizontal asymptote. If there is a horizontal asymptote, "

"

"

"

find the equation of the asymptote.

Analyze"

"

"

The problem says to determine whether there is a horizontal asymptote, "

"

"

and if so, to determine the equation of the asymptote.

Example problem" "

"

Given the rational function h(x) =

Formulate" "

"

Use the degrees of the leading coefficients of the numerator and "

"

"

denominator to determine whether there is a horizontal asymptote.

Determine" "

"

The degrees of the leading coefficients are 2 and 3 for the numerator and "

"

"

"

"

denominator, respectively. Thus, there is a horizontal asymptote at y = 0.

Justify"

"

"

The horizontal asymptote at y = 0 can be verified by looking at the "

"

"

function on a graphing device.

Evaluate"

"

"

The process for finding the equation of the horizontal asymptote was "

"

"

"

straightforward and quick. The solution is reasonable because the graph "

"

"

"

of the function h(x) appears to approach 0.

"

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

473

Section continues

8.3 - Asymptotes

Asymptotes & Translations

Transformations of the rational parent function affect the location of both the graph and asymptotes of

1

the function. The rational parent function, f(x) = , has a vertical asymptote at x = 0 and a horizontal

x

asymptote at y = 0, as shown in Figure 8.3-7.

1

+ a. The translation has a

x

vertical shift up or down a units, and the horizontal asymptote shifts from y = 0 to y = a.

The rational parent function with a vertical translation is in the form f(x) =

Jump to Rational Transformations

A rational function with a horizontal

1

, where

translation is in the form f(x) =

x−b

there is a horizontal shift right or left b units.

In this situation, the vertical asymptote shifts

from x = 0 to x = b.

1

+3

x−2

shifts up three units and right two units. The

For example, the function k(x) =

vertical asymptote of the parent function

shifts from x = 0 to x = 2, and the horizontal

asymptote shifts from y = 0 to y = 3, as

shown in Figure 8.3-8.

Figure 8.3-7 The rational parent function has both a

vertical and horizontal asymptote.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

474

Figure 8.3-8 This figure shows the parent rational

function translated up three units and right two units.

The red dashed lines are the asymptotes of the parent

function and the blue dashed lines are the asymptotes

of the translated function.

Section complete

Section 8.4

Rational Equations

Objectives

• Formulate and solve rational equations

• Determine the reasonableness of a solution to a rational

equation

New Vocabulary

• Rational equation

Many aspects of life and the physical world are described by dividing one number by another. Productivity is measured by completed items divided

by time spent, as in products per hour. The speed of a vehicle is measured in miles per hour or kilometers per hour. The frequency of sound or

light is measured in cycles per second, or hertz. A parking meter measures time in terms of money. What other ratios can you think of that describe

the world around you?

8.4 - Rational Equations

Formulating Rational Equations

A rational equation is an equation that contains a rational expression. A rational expression is

characterized as one polynomial expression, p(x), divided by another polynomial expression, q(x).

Verbally, these relationships can be expressed by stating the two expressions and that one is divided by

the other and what that quotient equals. In practice, though, such statements may be quite subtle.

For example, a delivery driver wants to know which route to take in order to make as many deliveries

to the same factory as possible. The driver maps out the routes, estimates the distances on the various

roads, and determines the speed of travel on each. The driver finds the three routes listed in Table 8.4-1.

D

Average speed can be described as the distance traveled during a given trip duration: S = . Using this

T

definition, the time on a route (the trip duration) can be solved for by rearranging the relationship

D

between time and speed to give T = .

S

The time taken for the different routes is approximately

15

8

= 0.231 h on the highway,

= 0.178 h on

65

45

5

= 0.227 h on city streets only. In an eight-hour day of

22

round-trip deliveries, the driver can make 22 deliveries using the 8 mi route and only 17 deliveries on

combined highway and city streets, and

the other routes.

When a relationship is described by one thing happening with respect to another, then

that relationship can be represented by a rational expression. Algebraically, a rational

relationship consists of a numerator that is being acted upon by the denominator. For

instance, speed can be defined in miles traveled during a unit of time, or miles per hour.

The productivity of a farm depends on the number of plants or animals that can be raised

on a given amount of land, for example, plants or animals per square kilometer.

Routes

Distance

Average speed

Highway only

15 mi

65 mph

8 mi

45 mph

5 mi

22 mph

Highway and

city streets

City streets only

Table 8.4-1 By rearranging the definition of speed, the time taken

on each route can be determined.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

476

Section continues

8.4 - Rational Equations

Example problem" "

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

Monique is testing commuter transportation for a reviewing service and wants to find the most fuel-efficient mode of transportation among three different options. She finds that the first mode of transportation, a truck, can go 330 mi on its 18 gal tank. The second mode, a car, travels 295 mi on its 12-gal tank. The third mode is a moped that can travel 50 mi with a

2 gal tank. What ratio can she use to describe the fuel efficiency? Which of the three vehicles is the most fuel-efficient?

Analyze"

"

"

The question asks for a comparison of the three vehicles’ efficiency and an equation to describe that efficiency.

Formulate" "

"

The relationship between miles traveled and fuel used can be described as a ratio of those values. Select a vehicle type, calculate "

"

"

the ratios, and compare them to identify the most fuel-efficient mode of transportation.

Determine" "

"

Two possible ratios can describe this relationship: miles per gallon or gallons per mile.

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

The miles per gallon for each mode of transportation can be determined by dividing the number of mi by the number of gallons in the tank. The most efficient mode of transportation would travel the most miles per gallon of fuel.

For the truck, 330/18 = 18.333 mpg.

For the car, 295/12 = 24.583 mpg.

For the moped, 50/2 = 25 mpg.

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

The gallons per mile for each mode of transportation can be determined by dividing the number of gallons in the tank by the number of miles traveled. The most efficient mode of transportation would use the least gallons of fuel per mile traveled.

For the truck, 18/330 = 0.055 gal/mi.

For the car, 12/295 = 0.041 gal/mi.

For the moped, 2/50 = 0.04 gal/mi.

"

"

"

"

Both methods show that the moped has the best fuel efficiency.

Justify"

"

"

"

"

"

"

A ratio of miles and gallons was used to compare fuel efficiency. A mode of transportation is more fuel-efficient if it travels farther on the same amount of fuel or if it uses less fuel for the same distance traveled.

Evaluate"

"

"

"

"

"

"

Creating a ratio of the two values allowed them to be compared, but the values’ position as numerator or denominator determined how to interpret the ratio.

"

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

477

Section continues

8.4 - Rational Equations

Solving Rational Equations

Rational expressions are composed of one polynomial expression divided by another. Care must be

Steps

Explanations

4

6

= ,x≠0

14x

7

The denominator 4

6 2x

=

14x

7 ( 2x )

Rewrite both sides with a

taken to restrict the unknowns so that the denominator does not equal 0 because division by 0 is

undefined.

In the equation shown in Table 8.4-2, two expressions are set equal to one another. In order to solve

this equation, the domain must be restricted, then both sides can be rewritten as ratios with the

same denominator. This step is similar to the process involved in adding two fractions. The

denominators can be canceled when both terms have the same denominator and the denominators

are not equal to 0. What remains is a typical algebraic expression that can be solved for x.

Simplifying a rational equation can be accomplished in more than one way. Another approach is to

12x

4

=

14x

14x

cross multiply the numerators with the denominators, as shown in Table 8.4-3. It is still necessary to

restrict the unknown so that the denominators do not equal 0.

Steps

3

2

=

, x ≠ − 4, x = 0

x+4

3x

3 ⋅ 3x = 2(x + 4)!

4 = 12x

Explanations

The denominator cannot equal 0.

Cross multiply the numerators x=

1

3

cannot equal 0.

common denominator.

Now the denominators

match and cannot equal 0.

Cancel the common

denominators.

Solve for x.

Table 8.4-2 This table demonstrates one way to solve a rational

equation: by canceling common denominators.

and the denominators.

9x = 2x + 8!

Simplify.

x = 8/7!

Solve for x.

Table 8.4-3 This table demonstrates another way to solve a rational equation: by cross multiplying

numerators and denominators.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

478

Section continues

8.4 - Rational Equations

Example problem" "

Solve the following equation for the value of x:

25

1

=

x−9

x−3

Analyze"

"

"

The problem asks for the value of x that satisfies the equation.

Formulate" "

"

First, restrict x in the equation so that the denominator will not equal 0. Then, use cross "

"

"

"

multiplication to rewrite the rational equation as one with no denominators. Finally solve "

"

"

"

the rewritten equation.

Determine" "

"

"

"

"

"

1

25

=

"

x−9

x−3

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

x ≠ 9, x ≠ 3

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

24x = 222

"

"

"

"

x = 111/12 = 9.25" "

Justify"

"

"

The solution to the problem is x = 9.25. This answer is obtained by cross multiplication and "

"

"

algebraic simplification. The domain is restricted so that it is not possible to divide by 0.

Evaluate"

"

"

This method modified the rational equation into a more familiar form, with the caveat of the "

"

"

"

restricted domain. The answer is reasonable because it is not one of the values restricted by "

"

"

"

the denominator.

"

"

"

Restrict the unknown so that the denominators will not "

"

equal 0.

x − 3 = 25(x − 9)" "

"

Cross multiply the numerators and the denominators.

x − 3 = 25x − 225" "

"

Simplify.

"

Solve for x.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

479

Section continues

8.4 - Rational Equations

Determining the Reasonableness of Rational Solutions

As with any equation used to model a real-world situation, a solution of a rational equation should be

checked to make sure it is reasonable. One way to check a solution for reasonableness is to determine

whether the answer is in the domain of the relationship modeled by the rational equation. For example,

a model that compared production levels of different workloads should not have negative solutions.

Failing to restrict the domain for a rational equation can result in extraneous solutions. For instance,

(x − 2)2

consider the 0 of the equation f(x) =

. The x − 2 term in the denominator can be canceled,

(x − 2)

leaving f(x) = x − 2 = 0, or x = 2. However, this result was obtained without considering the domain

restriction of the initial equation. The domain of f(x) can be written −∞ < x < 2, 2 < x < ∞, or simply

x ≠ 2. As a result, f(x) has no 0’s because at no point in its domain is f(x) = 0 true. In this case, the point

where the solution would exist but is restricted is an extraneous solution. This is shown graphically in

Figure 8.4-1.

The example illustrates that restricting the domain is pivotal in finding the correct solutions to rational

equations. All reasonable solutions must be in the domain as defined by the initial equation. As with

other equations, solutions to rational equations also must be considered within the context of the

problem to check for reasonableness. Another example of a solution that would be unreasonable is a

negative volume.

Figure 8.4-1 This graph shows a function with a

restriction on the domain.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

480

Section continues

8.4 - Rational Equations

Example problem" "

June owns a business where she sells custom machine tools. Every tool takes a minimum of 5 h of construction. As a result, "

"

"

"

work time is always a factor in delivering a good product while trying to keep production costs low. Her accountant has "

"

"

"

examined her business model and created an equation to describe the optimal number of hours (t) to construct each tool:

t − 10

14

=

"

t−3

5t

"

"

"

"

What restrictions are there on t? What is the solution of this equation? Round all answers to two decimal places.

"

"

The problem asks for the restrictions on and solutions of t.

Formulate" "

"

Because the equation is rational, the domain of t will need to first be determined. This may identify some restrictions on t. "

"

"

"

Once the domain is determined, solve the problem by finding a common denominator or, if that is not possible, by cross "

"

"

"

multiplication.

Determine" "

"

The domain given by the denominators is t ≠ 0, t ≠ 3. Furthermore, the time taken to construct a part cannot be negative, "

"

"

"

and a minimum time is given as t > 5.

"

"

"

"

5t(t − 10) = 14(t − 3)"

Analyze"

"

"

Use cross multiplication to rewrite the rational equation without denominators.

"

"

Solve for t using the quadratic formula.

2

5t − 50t = 14t − 42

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

5t 2 − 64t + 42 = 0" "

"

"

"

"

t=

"

"

"

"

t = 0.69, 12.11"

"

"

"

Find the possible solutions, rounding to two decimal places.

"

"

"

"

t = 12.11 h" "

"

"

"

Give the actual solution, taking domain restrictions into account.

Justify"

"

"

The solution is 12.11 h. The quadratic formula yields two solutions, but one is not reasonable in the context of the scenario.

Evaluate"

"

"

There was no common denominator, so cross multiplication was used and worked well. The final answer makes sense "

"

"

because it solves the initial equation and is within the domain.

"

64 ±

642 − 840

10

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

481

Section complete

Section 8.5

Rational Function Applications

Objectives

• Solve real-world problems involving

rational relationships

The applications of rational functions in the

real world are endless. If a utility company

wishes to cut pollutants caused by burning

coal to produce electricity, it will incur

additional costs. Consider the rational

65000p

, where C is the cost

formula C =

(100 − p)

to remove the pollutants, and p is the

percentage of the pollutants to remove. If

the state’s legislature mandates that 95% of

the pollutants be removed, what is the

additional cost for the utility company?

8.5 - Rational Function Applications

Biological & Medical Applications

Recall that a rational function is of the form f(x) =

p(x)

q(x)

, and where p(x) and q(x) are both polynomials.

Science has many real-world applications of rational functions. In biology and medicine, rational

functions are used in relation to animals’ running speed, oceanic temperatures, hospital costs, drug

concentrations and conversions, and body mass index calculations.

With regard to medication, a patient might need to be injected with medicine before surgery, as shown

in Figure 8.5-1. One purpose of this is to ensure that the patient does not feel any discomfort. Therefore,

the surgeon would not begin until the drug has taken. A rational function can be used to determine how

long a sufficient concentration of medicine will remain in the patient’s bloodstream.

The graph in Figure 8.5-2 is an example of what the function might look like during the stages of

dosage. The distribution phase contains a large concentration of the drug because it has not had time to

wear off. However, the concentration drops as time goes on and the drug begins to fade. The formula

for the drug concentration will depend upon the drug used, the dosage plan, and the physiology of the

patient.

Figure 8.5-1 This is a photograph of a doctor injecting

medicine into a patient.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

Figure 8.5-2 This is an example of what the function might

look like during the stages of dosage.

483

Section continues

8.5 - Rational Function Applications

Example problem" "

A patient is entering surgery, and a dosage of medicine is administered intravenously. "

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

Approximately what percentage of the drug is still in the patient’s bloodstream 3.5 h later if 8t

, where time (t) is the concentration is modeled by the rational function C(t) = 2

4t + 5.3

measured in hours, and drug concentration (C) is measured as a percentage?

Analyze"

"

"

The problem involves using a rational function to find the percentage of a drug that is still "

"

"

in the patient’s bloodstream after a certain amount of time.

Formulate" "

"

Begin by substituting the given time in the rational function. To solve this equation for C, first, "

"

"

"

simplify the numerator and denominator. Then, solve for C and determine the approximate "

"

"

"

percentage this indicates.

Determine" "

"

C(t) =

"

"

"

"

C(t) =

"

"

"

"

#

#

#

#

C(t) = 51.6%##

Justify"

"

"

The percentage of drug still in the patient’s bloodstream after 3.5 h was found to be approximately "

"

"

"

51.6%. This percentage was found by substituting the value for t into the equation and simplifying "

"

"

"

by following order of operations.

Evaluate"

"

"

Solving for C leads to a percentage of 51.6%. This value indicates that more than half of the drug is "

"

"

"

still in the bloodstream 3.5 h after it is administered. This seems reasonable because surgeries can "

"

"

"

last for several hours, and surgeons would want enough of the drug to last for the duration of "

"

"

"

the procedure.

"

8(3.5)

4(3.5) + 5.3

28

2

"

4(12.25) + 5.3

28

= 0.516"

C(t) =

54.3

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

#

"

"

"

Substitute 3.5 h for the time in the given formula.

"

"

Simplify the numerator and denominator.

"

"

Solve for C.

#

#

Determine the percentage by moving the decimal.

484

Section continues

8.5 - Rational Function Applications

Engineering Applications

Rational functions have applications in engineering fields, such as aerodynamics, manufacturing

efficiency, optics, and electricity. With regard to optics, the Hubble Space Telescope pictured in Figure

8.5-3 has been orbiting the Earth since 1990 for the purpose of observing objects. It uses mirrors, shown

in Figure 8.5-4, rather than a lens for many reasons, but largely because light is always lost when

passing through a lens but not when reflecting off a mirror. Factors such as light, the telescope’s

position above the atmosphere, and its mirror quality all affect its image quality. Another important

characteristic of a telescope such as the Hubble is something called the f-number, which is the ratio of

focal length

.

focal length to the diameter: f-number =

diameter

In addition to the rational function used to calculate the f-number of a telescope, two other rational

formulas can be implemented in relation to lenses. It is crucial for scientists and engineers to know the

exact measurements of the object versus the inverted image displayed.

Figure 8.5-3 This is a photograph of the Hubble Space

Telescope.

The lens equation below expresses the relationship among the focal length (f), distance of the object

(do), and the distance of the image (di):

1

1

1

=

+ "

f

do d i

The magnification equation relates the distances of the object

and image to the height of the object (ho) and image (hi),

respectively. The negative symbol in this equation accounts for

the inverted image that is received through this process:

di

hi

=− "

M=

ho

do

Figure 8.5-5 illustrates these equations. This diagram also

Figure 8.5-4 This is a

photograph of engineers

inspecting the primary mirror

of the Hubble Space

Telescope.

Figure 8.5-5 This is a diagram that illustrates the lens

equation and magnification equation.

shows how the optical system works to produce an image of

high quality.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

485

Section continues

8.5 - Rational Function Applications

Example problem" "

A tree that is 9 ft tall is located at a distance of 58 ft away from a double convex lens with a focal length of 14.5 ft. Find the "

"

size of the image (hi) and its distance from the lens (di).

"

"

The problem involves using the lens and magnification equations to find the image distance and image height.

Formulate" "

"

First, find the distance from the lens to the image by substituting the known values into the lens equation and solving for di. "

"

"

Then, use the image distance and other known values in the magnification equation to solve for hi.

Determine" "

"

1

1

1

=

+ ""

f

do d i

"

"

Substitute the known values for focal length and object distance into the lens equation to "

"

"

"

"

"

"

solve for the image distance.

"

"

"

"

"

"

1

1

1

=

+

14.5

58 di

"

"

"

"

1

3

=

58

di

"

"

"

"

di =

"

"

The distance from the lens to the image is found to be approximately 19.3 ft.

"

"

"

"

"

"

Use the known values in the magnification equation to solve for the image height.

"

"

"

"

58/3

hi

=−

9

58

"

"

"

"

hi = − 3(9) = − 3" "

"

The height of the image is 3 ft, where the negative symbol indicates that the image is "

"

"

"

"

"

inverted.

Justify"

"

"

The lens and magnification equations are implemented with the given values in order to solve for the unknowns. The "

"

"

"

height of the image requires the values for image distance, object distance, and focal length. Therefore, the lens equation "

"

"

"

must be used first to find di = 58/3 ft. Once di is found, the magnification equation is used to solve for hi = − 3 ft.

"

"

Analyze"

"

58

"

"

3

hi

di

M=

=− "

ho

do

"

"

"

Evaluate"

"

"

Solving for hi yields a negative value. It is tempting to think that this problem has not been solved correctly. However, it is "

"

"

important to remember that an object is inverted in its image form, so this inversion is expressed as a negative height.

"

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

486

Section continues

8.5 - Rational Function Applications

Physics Applications

Rational functions have an abundance of applications in physics, including fields and forces, circuitry,

and acoustics. With regard to acoustics and sound, mathematics plays a large role. A vibrating object,

such as an instrument, speaker, or vocal cords, produces a sound wave, as seen in Figure 8.5-6. This

sound wave passes through a medium at a certain frequency that is typically measured in hertz (Hz).

Frequency is a measure of how many waves per second pass through the medium. One hertz is equal to

one vibration per second.

Frequency is connected indirectly with another sound wave feature called the period. The period is the

time it takes to get from one peak of the sound wave to the next. The rational relationship between

frequency (f) and period (p) are seen in the equation below:

f=

1

"

p

A small period, such as the third wave in Figure 8.5-7, indicates a high frequency (or high-pitched

sound) because the sound wave is vibrating fast. Conversely, a large period, such as the first wave in

Figure 8.5-7, indicates a low frequency (or low-pitched sound) because the sound wave is vibrating

slowly. Human ears can hear a wide range of frequencies, generally between 20 and 20,000 Hz.

Figure 8.5-6 This is a diagram showing a sound wave through air from a

speaker to a human ear.

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

487

Figure 8.5-7 This is a diagram showing three sound

waves with varying periods.

Section continues

8.5 - Rational Function Applications

Example problem" "

A woodpecker drums his beak on a tree eight times in 2 s. Find the period of the sound "

"

"

"

wave created by this scenario.

Analyze"

"

"

The problem involves using the relationship between frequency and period to find the "

"

"

period of a sound wave for a woodpecker drumming on a tree.

Formulate" "

"

First, determine the frequency based upon the given information. If the woodpecker drums "

"

"

"

eight times in 2 s, this can be converted to hertz. Then, use the rational equation for "

"

"

"

frequency and period to solve for the period.

Determine" "

"

f=

8 vibrations

= 4 Hz" "

2 s

"

Convert vibrations per second to hertz.

"

"

"

"

f=

1

""

p

"

"

"

"

Substitute the given frequency into the rational "

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

equation to solve for the period.

"

"

"

"

1

4=

p

"

"

"

"

p=

"

"

"

"

The period of this sound wave is one-fourth of a "

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

second.

Justify"

"

"

The rational equation showing the relationship between frequency and period must be "

"

"

"

implemented. Because the woodpecker knocks on the wood four times in 1 s, this is an "

"

"

"

equivalent relationship to the hertz measurement (vibrations per second). Once the "

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

frequency is established, it is used to solve for the period in the rational equation, which is 1

equal to s, or 0.25 s.

4

Evaluate"

"

"

Determining the frequency was necessary because that information was not initially "

"

"

"

provided in hertz. The period has an indirect relationship with the frequency, so it makes "

"

"

"

sense that the period is 1/4 when the frequency is 4.

"

1

""

4

"

Chapter 8 - Investigating Rational Equations

488

Section complete