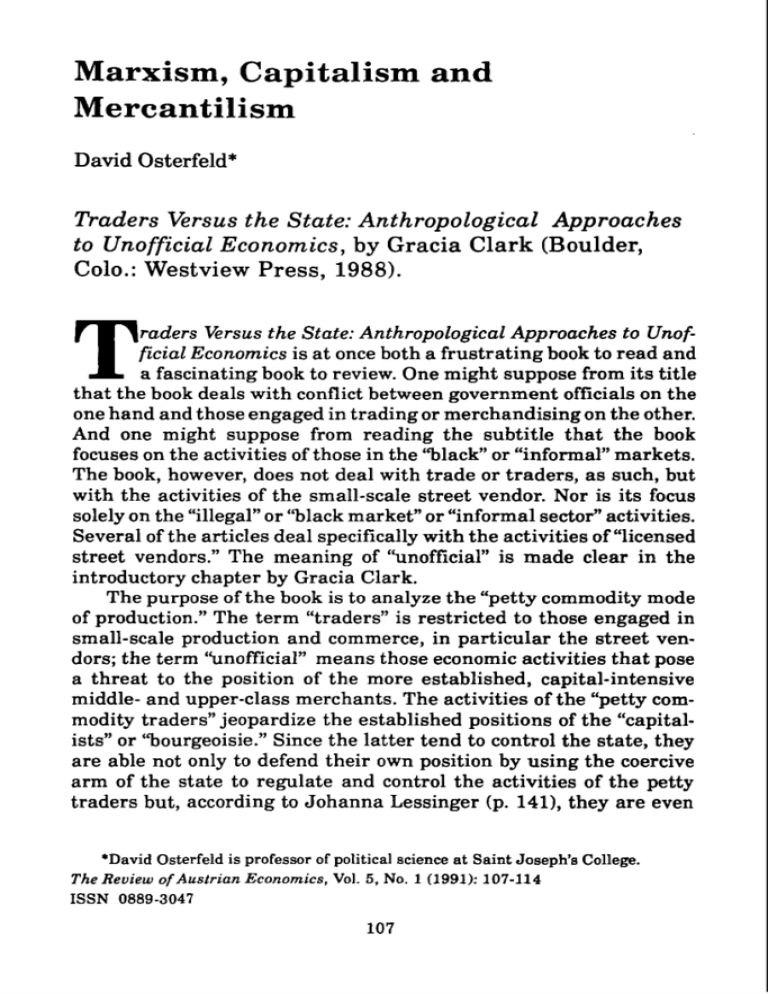

Marxism, Capitalism and Mercantilism

advertisement

Marxism, Capitalism and Mercantilism David Osterfeld* Traders Versus the State: Anthropological Approaches to Unofficial Economics, by Gracia Clark (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1988). T raders Versus the State: Anthropological Approaches to Unofficial Economics is at once both a frustrating book to read and a fascinating book to review. One might suppose from its title that the book deals with conflict between officials on the one hand and those engaged in tradingor merchandising on the other. And one might suppose from reading the subtitle that the book focuses on the activities of those in the "black" or "informal" markets. The book, however, does not deal with trade or traders, as such, but with the activities of the small-scale street vendor. Nor is its focus solely on the "illegal" or "black market" or "informal sector" activities. Several of the articles deal specifically with the activities of "licensed street vendors." The meaning of "unofficial" is made clear in the introductory chapter by Gracia Clark. The purpose of the book is to analyze the "petty commodity mode of production." The term "traders" is restricted to those engaged in small-scale production and commerce, in particular the street vendors; the term "unofficial" means those economic activities that pose a threat to the position of the more established, capital-intensive middle- and upper-class merchants. The activities of the "petty commodity traders" jeopardize the established positions of the "capitalists" or "bourgeoisie." Since the latter tend to control the state, they are able not only to defend their own position by using the coercive arm of the state to regulate and control the activities of the petty traders but, according to Johanna Lessinger (p. 141),they are even *David Osterfeld is professor of political science at Saint Joseph's College. The Review of Austrian Economics, Vol. 5 , No. 1 (1991):107-114 ISSN 0889-3047 108 The Review of Austrian Economics, Vol. 5, No. 1 able to enhance their positions by using the state to "appropriate the often sizeable patches of real estate on which existing markets are located," thereby facilitating "the process of capitalist development." Thus, she concludes, "the process of capitalist development has a very direct role in accentuating class differences," as the bourgeoisie continually solidify and improve their positions a t the expense of the poor, whose position deteriorates over time. The origins and growth of "petty commerce" is traceable, according to Florence Babb (p. 30), "to the contradictory, and uneven development of capitalism. . . ." In short, the real enemies of the "traders," who are actually small scale street vendors, is not so much the state but the "bourgeoisie" who control the state and use it for their own purposes. Traders Versus the State would be more accurately entitled: Street Vendors Versus the Middle Class Merchants. A more appropriate subtitle would be: A Marxist Viewpoint. The lengths to which one can go in order to blame all evils on "capitalism" is illustrated in the article on the "Informal Trade Sector in Tanzania" by Donna Kerner. Kerner notes that President Julius Nyerere committed Tanzania to a policy of "socialist development" as early as 1967, required peasants to market their food crops through "parastatal crop authorities," i.e., state-run marketing boards; introduced a policy of massive price controls; and nationalized the banks and nearly all businesses and labor unions. These policies resulted in massive shortages and extensive black market activities. The government responded to the economic crisis by mandating that "every able-bodied citizen" be "engaged in productive labor," and defining "labor" so as to exclude traders or "intermediaries." It then began a massive campaign of arresting"job1ess loiterers" and sending them to work on government-owned plantations. Within three months well over 15,000 "random arrests" had been made. This only aggravated the shortages, making the economic crisis more severe. The government responded to the extensive black-market activities by introducing a program known as 'The War Against Economic Sabotage." The program mobilized the police and military to arrest nearly everyone engaged in trade as an "enemy of socialism." Eventually, with economic output below 50%, many essential items completely disappearing, and the country on the brink of massive starvation, Tanzania, under pressure from the World Bank and the IMF, abandoned many of its interventionist policies. The result, according to Kerner, is that "recent reports indicate that imported and local goods now flood the government stores." Yet, astonishingly, the Tanzanian tragedy is blamed not on Nyerere's commitment to socialism; nor is it blamed on the interventionist measures designed to elimi- Review Essay 109 nate private trading. It is blamed on capitalism! Tanzania exists on "the periphery of international capitalism," she says, and what took place in that country represents "a distorted form of capitalism." The Marxist jargon that permeates most of the articles in Traders Versus the State is irritating, as is the Leninist penchant for referring to any multinational corporation such a s Purina or Nestle as a "monopoly." (Although the two notable exceptions are the superb articles on the economics and strategies of street hawking in Hong Kong by Josephine and Alan Smart. The articles deal with such things a s the use of roof-top spotters, armed with walkie-talkies, to provide hawkers with a sort of early-warning system when the police are approaching. The articles, it should be noted, are devoid of ideological terminology.) But in order to understand the book's significance it is first necessary to clarify two distinct approaches or "paradigms" to political economy: the Marxist and the classical liberal. Marxism, Liberalism and Power Nearly all the articles in Traders Versus the State are based on the Marxist paradigm. There are numerous references to class conflict and the contradictions of capitalism. Economics is viewed as a system of power relations, or as a zero-sum game, in which one person's gain is offset by another's loss. Since both the market and the state are tools which are used by the wealthy elite to protect and enhance their own privileged positions by oppressing and exploiting the poorer, working class, there is no need to distinguish between them. The market no less than the state is an institution infused with power relationships. This, of course, is in direct contrast to the liberal paradigm in which power relations simply do not exist on the market. The market is nothing more than the nexus of voluntary exchange. And precisely because it is voluntary, any exchange must therefore be to the mutual benefit of all parties concerned; if this were not the case, then the exchange would not be consummated. Thus, for the liberal, exchange is a positive-sum process. Capitalism and Mercantilism But these two outlooks are not a s incompatible as they may appear a t first. For the liberal free trade is positive-sum, but coerced trade is not. While the market is a purely voluntary institution, i t is in the state-the apparatus of compulsion and control-that power is concentrated. This means that the distinction between the market and the state, far from being meaningless a s it is for the Marxist, is, for the liberal, fundamental. Since the Marxist views both the market 110 The Review of Austrian Economics, Vol. 5, No. 1 and the state as nothing more than alternative methods by which the ruling class is able to dominate and exploit the rest of society, he is unable to distinguish between the market process itself, and the effect of government restrictions on the market. Arid this, in turn, means that the Marxist cannot distinguish between what is commonly referred to a s capitalism, or a system of free trade, and mercantilism, or a system in which the operation of the market i s impeded by extensive government restrictions for t h e benefit of the ruling group. It is important to realize that it is not simply that the Marxist does not distinguish between capitalism and mercantilism. It is that the Marxist paradigm quite literally renders him incapable of making such a distinction. As Robert Schenk (1986, p. 676) has put it: At the center of neoclassical analysis is mutually advantageous exchange. At the center of radical [Marxist] analysis are power relationships in the form of class conflicts. Any framework or paradigm focuses attention on certain features of the subject under investigation. Imperialism, exploitation and alienation flow readily from a framework emphasizing power. . . . To extend the framework of power relationships into socialism would deny the essence of what radicals want to achieve with socialism-a society without power relationships. . . . [But] if a theory of socialism is based on a framework other than power relations, another problem will arise. Trying to integrate such a theory with the core of radical analysis could force changes in the original paradigm. For example, the radical literature has rejected theories of market socialism because they need the concept of voluntary exchange, and voluntary exchange does not fit well with radical analysis. In contrast, the strength of the liberal paradigm lies in precisely its ability to provide a n analytical distinction between voluntarism and power, market, and government. This distinction has been a t the center of liberal thought from its very inception. Adam Smith, for example, wrote his massive Wealth of Nations specifically to refute the doctrine of mercantilism. Smith argues t h a t under mercantilism monopolistic privileges were granted to a few favored firms, permitting them to sell a t exorbitant prices, while tariffs were enacted to keep out foreign competitors. But if a nation were to eliminate imports it would need to have its own exclusive colonies in order to obtain raw materials. The power of the state, of course, was ideally suited to carve out and police the resulting colonial system. Smith charged that the mercantilist system not only hurt those in the colonies but the workers in the mother country a s well. Its only beneficiaries, he says, were "the rich and powerful." Permitting the Review Essay 111 colonists to buy only from merchants in the mother country enabled those merchants to sell a t monopoly prices in the colonies. The colonists, therefore, were unable to pay for the administration of colonial government as well, so the workers in the home-country were heavily taxed to defray this cost, thereby perpetuating the profits of the state-favored merchants. The effect of mercantilism, said Smith, was that "the interest of one little order of men in one country" was promoted a t the expense of "the interests of all other orders of men in that country and of all other orders of men in all other countries" (Smith 1776, p. 578). What Smith urged was the replacement of mercantilism by free trade. This, of course, would logically entail the abandonment of the entire colonial empire and Smith did not shrink from drawing that conclusion. One finds similar statements in the writings of other early liberal thinkers including J . B. Say, Charles Comte, and Charles Donoyer in France (Weinberg 1978; Liggio 1977), John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon (1965; this is the first reprinting of the Cato Papers since 1755), and Richard Cobden and John Bright (Read 1968) in England, and William Leggett and the Locofocos (Leggett 1984; Dorfman 1946, pp. 652-61; Hofstadter 1948, pp. 45-62) a s well a s the quasi-liberal, John C. Calhoun (1953; see also Hofstadter 1948, pp. 68-92) in America, to name but a few. Moreover, the distinction between market and government, between voluntarism and power, has remained a t the core of liberal thought down to the present. For example, Ludwig von Mises has written (1978, pp. 3-41 that: Our age is full of serious conflicts of economic interests. But these conflicts are not inherent in the operation of the unhampered capitalist economy. They are the necessary outcome of government policies interfering with the operation of the market. . . They are brought about by the fact that mankind has gone back to group privileges and thereby to a new caste system. While Mises sees peace a s the necessary precondition for free trade, mercantilism, he says tersely, is "the philosophy of war." Similarly, Murray Rothbard (1970, pp. 194-96) draws a sharp contrast between the market principle, personified by individual freedom, mutual harmony and peace, and the state, or "the hegemonic principle," characterized by "coercion," the '%benefit of one group a t the expense of another," "caste conflict," and "war." Similarly, Milton Friedman is fond of drawing attention to the fact that while such policies a s tariffs are "pro-business," they are "anti-free trade." The inability of the Marxist paradigm to distinguish between capitalism and mercantilism has resulted in an unfortunate termino- 112 The Review of Austrian Economics, Vol. 5, No. 1 logical confusion which has meant that classical liberals and Marxists have often talked past one another when they were, in fact, in substantial agreement, at least on certain key issues regarding the state, such a s its role in generating class conflict and turning trade into a situation in which one group benefits a t the expense of another. This is precisely the case with Traders Versus the State. What the authors of Traders Versus the State condemn a s "capitalism" is nearly identical to what liberals criticize as "mercantilism." I n t e r v e n t i o n i s m a n d Social Conflict The problem, so graphically underscored in Traders Versus the State, is t h a t in today's world, trade, especially in the Third World, is seldom free. The significance of Traders Versus the State is to show that in those societies in which the economy is highly politicized, where what one gets is determined largely if not solely by the state, one cannot say that "I am going to live my life in this way and allow others to live their lives in their own way." Rather, one must say that "In order to live my life in this way I must first get control of the state and impose my lifestyle on everyone else." As a result, control of the state becomes a prerequisite for obtaining any of one's goals. The result is that what would otherwise be handled by peaceful cooperation between individuals is transformed into bitter conflict between groups for control of the state. What would otherwise be handled through the mechanism of voluntary exchange for mutual benefit is turned into coerced exchange in which one individual or group benefits itself a t the expense of everyone else. A vital question is who is likely to get control of the state? As the articles by Florence Babb on Peru and Barbara Lessinger on India make clear, it is the wealthy merchants, or "capitalists," who are often in a position to use their wealth to gain control of the state. But it i s here that the distinction between capitalism a s a n economic system and the actions of the so-called "capitalists" is fundamental. The "capitalists" have little interest in free trade, a s such; their goal is to make money. In fact, it is because the never-ending threat of competition on the free market renders their position perpetually insecure that the "capitalists" strive to control the state. Put differently, far from the market being a n institution of power on a par with the state, as the Marxists believe, the only reason the "capitalists" seek to control the state is precisely because the vaunted notion of "market power" or "economic domination" simply does not exist on the unhampered market. Thus, it is only through control of the state that the "capitalists" are able to control access to the market, thereby institutionalizing their economic positions. Review Essay 113 But, perhaps ironically, Traders Versus the State also shows that the state may, and has, been dominated by a very different group. This group despises trading not for pragmatic but for ideological reasons, viz., because of its commitment to socialism or communism. Traders are seen a s useless intermediaries and trade as exploitation which must be stamped out. The extent to which the war against trading will be taken by its ideological enemies-including the demolition of markets and the beating and even killing of the traders-is graphically documented in the articles by Donna Kerner on Tanzania and Gracia Clark on Ghana. Conclusion Two things come through crystal clear in Traders Versus the State. The first is that regardless of whether the state is controlled by the wealthy capitalists or the ideological socialists, the result of government economic intervention is the same: massive shortages, extensive black-market activities and social conflict. As Clark says of the situation in Ghana, "price controls brought chaos" (p. 63). The second is t h a t when the controls are lifted all three of the problems are reduced in intensity or even relieved altogether. As Babb has observed, with "the elimination of many price controls" in Tanzania, "goods now flood the government shops" (p. 51). These are certainly astonishing conclusions for a book written largely from a Marxist perspective. In the final analysis, the authors' candid acknowledgement of the indispensable role of the free market says far more about the intellectual bankruptcy of Marxian economics than a dozen books on that topic. References Calhoun, John C . [I8511 1953. A Disquisition on Government. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill. Dorfman, Joseph. 1946. The Economic Mind in American Civilization, 1606-1865. Vol 2. New York: Viking Press. Hofstadter, Richard. 1948. The American Political Tradition. New York: Vintage. Leggett, William. 1984. Democratic Editorials, Essays in Jacksonian Political Economy. Indianapolis: Liberty Press. Liggio, Leonard. 1977. "Charles Donoyer and French Classical Liberalism." Journal of Libertarian Studies (Summer): 153-78. 114 The Review of Austrian Economics, Vol. 5, No. 1 Mises, Ludwig von. 1978.The Clash of Group Interests and Other Essays. New York: Center for Libertarian Studies. Read, Donald. 1968.Cobden a n d Bright. New York: St. Martin's Press. Rothbard, Murray N. 1970. Power a n d Market: Government and the Economy. Menlo Park, Calif.: Institute for Humane Studies. Schenk, Robert. 1986."Communication: Keith Griffin and John Gurley, 'Radical Analyses of Imperialism, the Third World, and the Transition to Socialism: A Survey Article'." Journal of Economic Literature (June): 676. Smith, Adam. [I7761 1937. The Wealth of Nations. Edwin Cannan, ed. New York: Modern Library. Trenchard, John, and Gordon, Thomas. [I7551 1965. The English Libertarian Heritage. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill. Weinberg, Mark. 1978."The Social Analysis of Three Early 19th Century French Liberals: Say, Comte, and Donoyer." Journal of Libertarian Studies (Winter): 45-63.