Marbury v. Madison 1803 - Ramsey School District

advertisement

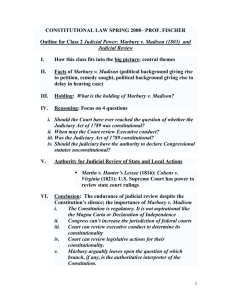

Marbury v. Madison 1803 Plaintiffs: William Marbury, William Harper, Robert R. Hooe, Dennis Ramsay Defendant: James Madison, U.S. Secretary of State Plaintiff’s Claim: That U.S. Secretary of State James Madison must deliver judicial commissions issued by his predecessor to their rightful recipients. Chief Lawyer of Plaintiffs: Charles Lee Chief Lawyer for Defendant: Levi Lincoln, U.S. Attorney General Justices for the Court: Samuel Chase, William Cushing, Chief Justice John Marshall, William Paterson, Bushrod Washington Justices Dissenting: None (Alfred Moore did not participate) Date of Decision: February 24, 1803 Decision: Ruled in favor of Madison by finding that the Judiciary Act of 1789 giving legal authority to federal courts to order government officials to act was unconstitutional. Significance: The ruling is considered by many the most important decision in American legal history. The Court established the guiding principles of judicial review which recognized the federal courts’ role in reviewing acts of Congress and states regarding their constitutionality. The Supreme Court thus became a significantly powerful part of the American governmental system. S u p r e m e C o u r t D r a m a 8 6 7 “It is, emphatically, the province [within court’s power] and duty of the FEDERAL POWERS AND SEPARATION OF POWERS judicial department [the courts] to say what the law is.” This dramatic and often quoted statement was made by Chief Justice John Marshall in Marbury v. Madison (1803). Often called the single most important decision in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court, Marbury established the power of judicial review. Judicial review allows federal courts to review laws enacted by Congress and to declare a law invalid if it is found to violate the Constitution. However, the Court may not invalidate (overturn) just any law merely because it violates the Constitution. Such a decision by the Court may be made only when a specific lawsuit is brought before the Court requiring a determination that a law is constitutional. Additionally, judicial review allows federal courts to see that government officials, including the president, act in accordance with constitutional principles. An Active, Living Constitution Unlike many constitutions of countries around the world, the Constitution of the United States is more than just a description of the existing governmental system. It is also an active, living instrument in which is found the source of power and limits of power among the three governmental branches. Chief Justice Marshall viewed the Constitution as a broad outline describing important goals. The details of how to carry out those goals, of how to fill in the outline, was left to the working government. But, which part of government would have the ultimate responsibility to guard the written terms of the Constitution and to see that the power of each branch of government was properly limited? This question was first debated at length in the Philadelphia Constitutional Convention of 1787. They found little guidance in the history of English law as to who should be the Constitution’s final interpreter. Although the Framers made it clear some sort of review of legislation needed to be established, the exact nature of the review was left undefined. In Federalist Paper No. 78, written by Alexander Hamilton (1757–1804 ) in 1788, the judiciary (courts) was described as the “least dangerous to the political rights of the Constitution.” Hamilton saw the executive branch, the president, as carrying the “sword” and the legislative branch (Congress) carrying the “purse” which could be opened or closed at the political whim of the day. But, he noted the Supreme Court held neither and likely would be the fairest defender of liberty. 8 6 8 S u p r e m e C o u r t D r a m a The answer came in 1803 in Marbury, a declaration that the Supreme Court would have the final say in guaranteeing that the intent of the Constitution was being carried out by the governmental branches. This decision was intertwined with the political scene of the day. The Politics of 1800 In 1800, two political parties dominated America, the Federalists and the anti-Federalists, who were called the Democratic-Republicans at the time. The Federalists, in power at Madison was charged with not delivering judicial the time with John commisions left over from the previous secretary. Adams (1797–1801) as Courtesy of the Library of Congress. president, believed in a strong national government to expand the country’s economic and geographic interests and protect U.S. citizens. The anti-Federalists, a leading member being Thomas Jefferson, believed a strong central government would weaken the power of the states, and, therefore, the people. The anti-Federalists sought to halt further growth of the national government. Thomas Jefferson became the anti-Federalist’s or Democratic-Republican party’s candidate against John Adams in the presidential election of 1800. The “Midnight Judges” After a bitter battle, Thomas Jefferson emerged in February of 1801 as the presidential victor. Adams and his party feared Jefferson would undo S u p r e m e C o u r t D r a m a 8 6 9 M a r b u r y v. Madison FEDERAL POWERS AND SEPARATION OF POWERS everything the Federalists had accomplished the past twelve years. He decided to pack the federal courts with as many new Federalist judges as possible before the Jefferson administration took power in March. Adams appointed his Secretary of State John Marshall to be Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. However, Marshall would remain Secretary of State through the last day of Adams’ term. Adams proceeded to nominate more that two hundred loyal Federalists to new judgeships including forty-two justices of the peace in the District of Columbia. The Senate confirmed the nominations of the justices of the peace on March 3, Adams’ last day in office. Working late into the night, Adams signed the commissions and Secretary of State Marshall placed the official seal of the U.S. government on them then supervised their delivery. The new judges became appropriately known as the “midnight judges.” During these moments of confusion, several of the commissions were not delivered, including one to William Marbury. Writ of Mandamus Jefferson became President the next day, March 4, and ordered the new Secretary of State, James Madison, not to deliver the remaining commissions. Marbury and several others who similarly did not receive their commission petitioned the Supreme Court, whose Chief Justice was now John Marshall, for a writ of mandamus, ordering Madison to deliver their commissions. An amusing twist to Marbury’s petition to the Court was that it was Chief Justice Marshall who had failed to deliver the commission the night of March 3. The writ of mandamus is a court order requiring a government official to take action and carry out his duties. In the Judiciary Act of 1789, Congress had authorized the Supreme Court to issue to federal officials writs of mandamus. A Skillfully Written Opinion Chief Justice Marshall wrote the opinion for a unanimous Court. Marshall, who history remembers as the greatest chief justice to serve, managed to craft a skillful opinion amid a highly charged political atmosphere. Marshall hoped to avoid a direct conflict with Jefferson, Madison, and the anti-Federalist whom he feared would simply say no if he ordered them to deliver the commissions. At the time, the Supreme Court had little recognized power to actually force other branches of the government to comply with its decisions. In an attempt to aid the growth of 8 7 0 S u p r e m e C o u r t D r a m a the young governmental system by deciding who would be the ultimate interpreter of the Constitution, Marshall established the principle of judicial review. The new principle allowed the Supreme Court to have final word on the meaning and application of the Constitution. Marshall’s historic opinion was divided into five parts. The first three parts were simple. First, Marbury had a legal right to be a justice of the peace. Second, Secretary of State Madison violated this right by withholding the commission. Third, the writ of mandamus was a proper way to direct a government official to carry out his duty. But, the question of who could issue the writ led to the fourth part of the ruling. A Cornerstone of the American System The fourth and fifth parts of the Marbury decision, brilliantly reasoned, established a cornerstone of the United States’ system of government. In the fourth part, Marshall considered whether or not the Supreme Court had the power, or in other words the jurisdiction, to issue a writ of mandamus. Article III of the U.S. Constitution gave the Supreme Court two types of jurisdiction, original and appellate. Original jurisdiction meant the Supreme Court could be the first court to receive a petition and hear the resulting case. Article III gave the Supreme Court original jurisdiction over politically sensitive issues such as those involving “ambassadors” or when one of the states was named as a party. In all other cases, the Supreme Court has appellate jurisdiction, meaning petitions or cases must work their way through the lower courts before arriving at the Supreme Court. Yet, section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 allowed the petitioning of the Supreme Court and all federal courts directly asking them to issue writs. Although Marbury was neither an ambassador nor a state government, the Judiciary Act gave him the right to petition the Supreme Court first. Marshall ruled that this legislation violated the intent of the Constitution by giving the Supreme Court original jurisdiction in matters not mentioned in Article III. He concluded the Judiciary Act was unconstitutional, therefore invalid and not enforceable by a court of law. As a result, the Supreme Court, in response to Marbury’s petition, could not issue the writ. This decision avoided a direct conflict with the Jefferson administration. At the same time, it also negated an act passed by Congress. Marshall wrote that it would be absurd to insist that the courts must uphold unconstitutional acts of the legislature. No act of Congress could do something forbidden by the Constitution. Marshall’s reasoning S u p r e m e C o u r t D r a m a 8 7 1 M a r b u r y v. Madison THE GREAT CHIEF JUSTICE FEDERAL POWERS AND SEPARATION OF POWERS From 1801 to 1835 John Marshall served as chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, writing 519 of the 1,100 opinions issued during that period. His personality dominated the Court and the justices who served with him. His opinions, brilliantly reasoned and masterfully written, transformed the Court into a powerful branch of the American government system. Born and raised in Virginia, Marshall was mainly educated by his father. An avid reader, he educated himself in law, taking only one formal law course at the College of William and Mary in 1780. Marshall served in the Continental Army during the American Revolution for almost six years and endured the harsh winter with George Washington at Valley Forge. From 1781 until his appointment to the Supreme Court in 1801, he held various government service jobs, first in Virginia and later as U.S. minister to France from 1797 to 1798, U.S. representative from Virginia from 1799 to 1800, and U.S. Secretary of State from 1800 to 1801. Marshall’s greatest decisions form the heart of commentary on the U.S. Constitution. He established judicial review of the courts over laws enacted by Congress and over acts of state government when either was challenged as not obeying the Constitution. His judgements defended the reliability of contracts and protected private property rights. He also convincingly argued that the Constitution was the permanent supreme law of the United States, to be interpreted by the Supreme Court. Marshall died in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania while still serving on the Court on July 6, 1835. established the Court’s power to declare an act of Congress unconstitutional — a monumental first which became a cornerstone of the American democratic system. Lastly, Marshall considered whether the judiciary was indeed the proper branch of government, as opposed to the executive (president) or 8 7 2 S u p r e m e C o u r t D r a m a legislative (Congress) to have the final authority to overturn unconstitutional legislation. Although by the year 2000 this had long been accepted, the Constitution did not actually identify which branch should have this power. Marshall, describing for the first time the doctrine of judicial review, stated that the federal courts, above all the Supreme Court, have the power to declare laws unenforceable if they violate the Constitution. Marshall wrote, “This is the very essence of judicial duty.” A Check on Legislative Power In 1801, when John Marshall became Chief Justice, the Supreme Court was considered weak and unimportant. The Marbury decision began its transformation into the most powerful judiciary in the world. Marbury provided reasoning for constitutional examination of laws by the courts. Although scholars have extensively debated the legal reasoning behind Marbury, the significance has never been challenged. Judicial review provided a clear check on the exercise of legislative power over the people. Suggestions for further reading Clinton, Robert L. Marbury v. Madison and Judicial Review. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1989. Hobson, Charles F. The Great Chief Justice: John Marshall and the Rule of Law. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2000. Schwartz, Bernard. A History of the Supreme Court. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995. S u p r e m e C o u r t D r a m a 8 7 3 M a r b u r y v. Madison