Wilson 1 Jenna Wilson Malory Klocke Analysis 24 July 2011 All You

advertisement

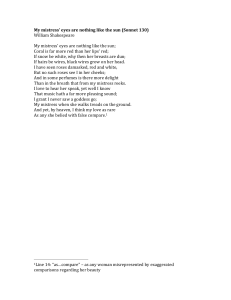

Wilson 1 Jenna Wilson Malory Klocke Analysis 24 July 2011 All You Need is Love William Shakespeare’s “When in disgrace with Fortune and men’s eyes,” also referred to as Sonnet 29, is centered on the power of love. He poetically illustrates the ability of love to change our disposition from depression to that of joy. The language used is very dramatic and emotional. Why does Shakespeare choose such emotional phrases, words and imagery? Is he manic-depressive or intentionally and artistically expressing the impact love can have on one’s life? Arguments can be made for both sides. Frank Bernhard, in “Shakespeare’s Sonnet 29,” looks at the use of dramatic imagery to speculate about the apparent lack of stability of the speaker in this sonnet. The octave, the first eight lines of the sonnet, is painted to be very dark and dreary. The speaker mourns his “outcast state.” The speaker has not only fallen on bad luck and out of favor with men but he is “in disgrace with Fortune and men’s eyes” (Shakespeare 93). The word “disgrace” suggests consequence for ill actions, “Fortune” is capitalized in the original and so alludes to a higher power and “men’s eyes” paint a picture of stares, glares and judgmental glances. The speaker seems to have done something disgraceful and feels the repercussions of his actions alienating him from God and neighbor. Shakespeare writes, “I all alone beweep my outcast state,” emphasizing the solitude by using “all alone” instead of merely “alone” (93). He does not write about his “lonely state” or his “unlucky” or “wretched state.” Shakespeare uses a stronger word, “outcast,” to illustrate how the speaker feels removed from and rejected by society. In his misery Wilson 2 he weeps “and trouble[s] deaf heaven with [his] bootless cries” (Shakespeare 93). He “troubles” heaven, implying that he is persistent in his supplication. But heaven is deaf to his cries; meaningless, they go unanswered and cause him greater desolation. “And [he] look[s] upon [him]self, and curse[s his] fate” (Shakespeare 93). Thomas Watson, in “Shakespeare’s Sonnet 29,” remarks that the faith of the speaker “has abandoned him in the first quatrain” (13). In the second quatrain of the octave, the speaker moves from a state of desolation to that of despair. “Wishing me like to one more rich in hope,” the speaker acknowledges that he is lacking hope and expresses his desire for hope by “wishing” to be like someone who has more hope than he. This reveals his despair, for “to wish” is to want something that is not easily attainable, that can never or probably will never happen. It is as if he despairs of ever having hope again (if he ever had it in the first place). This depressing spiral is made manifest in the next few lines of the quatrain. The speaker wishes he was “featur’d like him, like him with friends possess’d, / Desiring this man’s art, and that man’s scope” (Shakespeare 93). The speaker is discontented with his physical appearance and lack of friends, skill and future. Or as Frank Bernhard puts it, he is on “a mental rampage into a deep depression: a sense of hopelessness, an imagined lack of good looks, talent, and range” (138). The speaker proves his depression in the last line of the octave when he laments, “with what I most enjoy contented least” (Shakespeare 93). The depressed person looses interest in his hobbies, friends and the activities he formerly enjoyed. The speaker is no longer content in what he most enjoyed. In the sestet, a change takes place. Shakespeare writes, Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising. Haply I think on thee,–and then my state, Like to the lark at break of day arising From sullen earth, sings hymns at heaven’s gate; Wilson 3 For thy sweet love remember’d such wealth brings That then I scorn to change my state with kings. (93) The speaker, suffering in the depths of his despairing thoughts, almost despises himself. He previously cursed his state in life and wished he was like many others who had hope and opportunity, were better looking and popular, but does not actually loathe himself. The speaker walks a fine line of being dissatisfied to the point of disdaining his current position, situation and certain qualities or lack thereof of his personality, but he never expresses scorn for his very life. Bernhard offers a different view, writing: “once he has shredded himself mercilessly, the speaker adds, ‘myself almost despising.’ Almost? How much further could he go?” (138). He is kept from going any further when his thoughts, by chance, come to rest on one who loves him. The very thought of this person makes all the difference to his state of mind. He likens his uplifted mood to that of a bird taking flight at sunrise. Shakespeare uses a lark, a ground-dwelling bird known for his melodious tunes, the flight of the lark and the dawn to bring contrast to the previous darkness. As the lark soars upward from the “sullen earth” so is the speaker’s spirit uplifted to “sing hymns at heaven’s gate” (Shakespeare 93). Shakespeare’s use of the word “sullen” really draws the reader’s attention to the gloomy, sulky mood of the speaker in the octave making the contrast more apparent. The change is drastic; his “state […] sings at heaven’s gate” (Shakespeare 93). Singing and being placed at the gates of heaven show the joy and lightness of the speaker’s newfound state. He went from almost despising himself to being almost in heaven. The “wealth” that comes with this “sweet love” is such that the speaker would not trade his state with kings. The speaker “tears himself and his life apart with great zeal and rebounds with equal zeal by using the equivalent of an antidepressant drug. Here manic Wilson 4 depression raises its dire flag” (Bernhard 138). The speaker’s lows are despairingly low and his highs are euphorically high. The rapid shift in mood is another indicator for emotional instability. Or is it that love is strong enough on its own to bring about such a stark transformation? Watson takes a more spiritual interpretation, “though his faith and hope are weak, or absent, the realization that love abides and is indeed the greatest of the three biblical virtues [...] gifts Shakespeare’s persona with the awareness that his is a spiritual kingdom, not one of this world” (13). This awareness impacts the speaker deeply such that he is uplifted out of his depression to sings hymns at heaven’s gate. In both interpretations love is the catalyst that changes the speaker’s disposition and the lens from which he views his situation. This makes all the difference for him. His physical appearance, skills, number of friends, all the aspects of his life that were bringing him grief have not changed. He is situation does not change, but how he sees does. Love gives him a brighter perspective. He may still be an outcast in the eyes of society, but to the one who loves him, he is accepted and desirable. Shakespeare praises the positive impact love can have on the life of one who is aware that he is loved. It was only when the speaker thought of the sweet love of the lover that he was able to see in new way. It was not enough that the speaker was loved; the awareness of love is key for the transformation. This awareness can be lost or masked by other thoughts as evidenced in the octave. Nothing else matters to the speaker when he is conscious of his lover’s love for him. His depressing thoughts overwhelmed him in the beginning of the sonnet when he was not actively thinking of the lover. How long will he persevere in positive thinking? When, by chance his thoughts come to rest on what he does not have in “men’s eyes” and he loses sight of love, he will be back to almost despising himself again. Where is the lover in all of this? They must be physically separated and not in regular communication. But this Wilson 5 does not seem to bother the speaker who makes no mention of wishing to be near the one who loves him. The speaker rejoices in being loved. The sonnet is addressed to the lover praising the power of his love. Yet there is no apparent effort made to express love in return. There is an immaturity and instability in the speaker’s mental disposition. There is potential for growth and Shakespeare leaves that to the reader and/or future sonnets. As for “Sonnet 29”, it gives a glimpse of the transformation that is possible when one is aware that he is loved. It is a timeless tale of the power of love. Comment [mk1]: Wonderful, wonderful, wonderful!! This reads as though it has come from an upperclassmen English major. Your insights are fantastic and your use of sources is great. This was a true joy to read! Grade: 99/100 Works Cited Wilson 6 Bernhard, Frank. "Shakespeare’s Sonnet 29." Explicator. 64.3 (2006): 137-138. Academic Search Premier. Web. 19 July 2011. Shakespeare, William. "Sonnet 29." Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Ed. Carl D. Atkins. New Jersey: Rosemont, 2009. 93. Google Books. Web. 19 July 2011. Watson, Thomas Ramey. "Shakespeare’s Sonnet 29." Explicator. 45.1 (1986): 12-13. Academic Search Premier. Web. 19 July 2011.