Dream Boogie - Stephen Kessler

advertisement

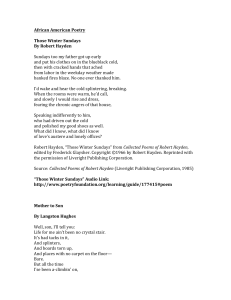

The Redwood Coast Review Volume 9, Number 2 Spring 2007 A Publication of Friends of Coast Community Library in Cooperation with the Independent Coast Observer It is not possible to go very far into Langston Hughes research without run­ ning into the name Arnold Rampersad. Dean of Humanities and Professor of English at Stanford University, Rampersad is the author of a two-volume biography, The Life of Langston Hughes. He has also contributed extensively in the form of essays and biographical sketches introduc­ ing Hughes and his work to readers of col­ lections, anthologies and children’s books. Hughes’s two volumes of autobiography, The Big Sea and I Wonder As I Wander, make for interesting and enjoyable read­ ing. Rampersad’s biography fills in lots of blanks, presenting a much more complex and conflicted individual. I came away from the Hughes books thinking that he was a wonderful writer and a courageous individual. From reading Rampersad, I have come to appreciate Hughes even more as a writer and human being. habitat The River in the Sky George Keithley M See sky page 4 J Gordon Parks y son and his wife are watching two sandpipers on the edge of a pond. Chris and Fiona have joined me at the Gray Lodge Wildlife Area, a refuge for migrating birds along the Pacific Flyway. A cold wind bends the huge bulrushes that surround us. It leans into them, then it ebbs, and they bow and sway. Their rustling is part of a gentle din—varieties of birdsong, the wind pushing the leafless brush and feathering the sedge grasses, wings now and then flapping at the water—interrupted by the complaining quacks of a grumpy duck. It’s not stillness, exactly, but a peace­ ful interplay of activity and silence. At Uskoye, in what was once a remote wet­ land region in pre-tsarist Russia, we’re told Alexander Pushkin later roamed among lakes and ponds no larger than these. High-spirited and Byronic, in black boots and his crimson cloak, he chanted his poems to test their sono­ rous texture in the vibrant natural world beyond the opulent salon or a prince’s paneled library or cloistered study. To his dismay the startled waterfowl bristled and squawked—everyone’s a critic—as they flapped into the air and took flight. In this wetland region of Northern California hundreds of ducks are win­ tering today, but many thousands have moved on. They were mallards, pintails, the ruddy duck, the ring-neck, the bluewinged teal. The unhappy loner is a wood duck. He’s an uncommon species in this locale in any season, and in the somber light his paint-bright coloring captures our attention. The crown of his head is iridescent green, the forehead and sides of the head are lustrous black, with white arc-shaped markings. His beak is black and white and a curious pomegranate orange, and his chin and throat are white. His scarlet eyes look fierce. But he seems simply puzzled at his solitary state as he paddles here and there, delivering his out­ spoken qreck-qreck, while sending ripples out among the rushes. The sandpipers, finding shelter in the marsh, ignore him. The marsh includes clumps of eel grass amid broad ponds where the water is jade blue under a pewter sky. In the distance, top­ping the tawny bulrushes, the cotton­ woods gleam with the pale gold of early winter. Six weeks ago much of this watery haven belonged to the ducks. Traveling south-by-southeast from Siberia, Canada, and Alaska, they gathered overhead in dark clouds—60,000 to 70,000 ducks bunched together in the sky. Then the deafening descent, wings thrashing the air and the water, until at last the flocks settled here to begin courting and mating. Cold rains drummed on the ponds. When the air cleared the pintails and teals whistled and the wood ducks quacked like the solitary straggler on the pond today. For days the foraging ducks filled these ponds and inlets with their characteristic “feeding chuckle.” Then they departed and a hush hung over the marsh. We stepped into that stillness an hour ago. Dream Boogie The epic journey of Langston Hughes Daniel Barth The world’s great political leaders— consider Jesus, Churchill, Lincoln, Lenin, Martin Luther King—have all drawn upon the beautiful rhythms, sounds and expressions found in everyday speech. So did Shakespeare, Mark Twain, Will Rogers, Woody Guthrie, Langston Hughes. F —Pete Seeger orty years after his death the work of Langston Hughes con­ tinues to be read widely and to influence contemporary art and culture. His 1958 novel Tambourines to Glory was recently reissued, many of his other books remain in print, and the 16-volume Collected Works of Langston Hughes was completed in 2003. Community centers, schools and libraries are named for him. A much-used elemen­ tary school history text, America Will Be, takes its title from one of his poems. That same poem, “Let America Be America Again,” was used as a theme by the John Kerry campaign, and a chapbook of Hughes poems with an Introduction by the Senator was published in 2004. Kentucky blues man Tyrone Cotton wrote music for a Hughes poem, “As Befits a Man,” and included it on a 2005 CD. In February of this year, at the Bowery Poetry Club in New York, a group of poets and musicians staged a two-hour tribute to Hughes’s life and work. Thornton Wilder once remarked that his literary career consisted of a succes­ sion of infatuations with admired writers. This is something that I think many of us who write can relate to. We all have our favorites. I remember my excite­ ment when I read Walt Whitman and Jack Kerouac for the first time. I wasn’t too impressionable—I took to the open road and got a summer Forest Service job as a firefighter. After reading Huckleberry Finn I started smoking a pipe. Later phases included Thomas Wolfe, J. D. Salinger, Hermann Hesse and Kurt Vonnegut. In recent years the writer who has grown more in my estimation and made a bigger impression on me than any other is Langston Hughes. I started getting into Hughes after reading several poems that knocked me out: “Dream Boogie,” “Har­ lem,” “The Weary Blues” and “Daybreak in Alabama.” I decided to read more of his work and to read about his life, starting with his early autobiography The Big Sea. I came away amazed by his life story and by how little I had heard about it previously. From the early 1920s through the late 1960s he traveled more and gave more readings than anybody, and had one of the most amazingly varied careers in the history of American letters. In addition to poems, novels and short stories, he wrote plays, song lyrics, children’s books, essays, dialogues (the “Simple” pieces, of which more later), biographies and histories. He also worked as a journal­ ist, editor and translator. He was the first African American to earn his living solely as a writer, and the first to have an interna­ tional reputation and following. Reviewers criticized his work for being too simplistic, for not adequately reflecting or expressing the complexities of the modern world. I don’t think those critics understood what he was after, or the complexities of minority experience that he did express. ames Langston Hughes was born February 1, 1902, in Joplin, Missouri. His father was a lawyer and businessman, his mother a would-be actress. Shortly after he was born his parents separated. Disdainful of segregation in the US, but also of Negroes who put up with it, his father moved to Mexico City to pursue his career. Langston was taken to Lawrence, Kansas, where he lived primarily with his maternal grandmother until he was 13 years old. His mother remarried and eventually moved to Lincoln, Illinois. Langston joined her and graduated from junior high there. In 1915 the family moved to Cleveland. Langston attended predominantly white Central High, where many of his friends were children of recent European immigrants. Hughes was precocious. He wrote passable poems ands stories while still in high school. By his senior year he was reading Guy de Maupassant in French and Vicente Blasco Ibáñez in Spanish. He credits de Maupassant with turning him on to the possibility of life as a writer. One of his best poems was written when he was just 18, after graduating from high school, as he rode a train to Mexico to visit his father. He writes about it in The Big Sea: Now it was just sunset, and we crossed the Mississippi slowly, over a long bridge. I looked out the window of the Pullman at the great muddy river flowing toward the heart of the South, and I began to think what that river, the old Mississippi, had meant to Negroes in the past—how to be sold down the river was the worst fate that could overtake a slave in times of bondage. Then I re­ membered reading how Abraham Lincoln had made a trip down the Mississippi on a raft to New Orleans, and how he had seen slavery at its worst, and had decided within himself that it should be removed from American life. Then I began to think about other rivers in our past—the Congo and the Niger and the Nile in Africa—and the thought came to me: ‘I’ve known riv­ ers,’ and I put it down on the back of an envelope I had in my pocket, and within the space of ten or fifteen minutes, as the train gathered speed in the dusk, I had written this poem, which I called “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.” He spent the next year in Mexico. His father had plans for him to study in Switzerland, but Langston felt the pull of Harlem and chose New York instead. He attended Columbia, but Harlem was his true university. There he met W. E. B. Du Bois, Claude McKay, Zora Neale Hurston, Countee Cullen and many others. He began publishing poetry and became a leading light of the Harlem Renaissance. After one academic year he never returned to Columbia. Later he completed his un­ See hughes page 10