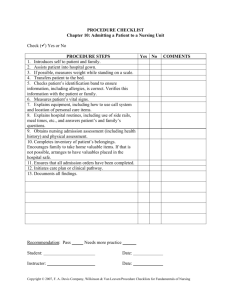

Critical Thinking, the Nursing Process, and Clinical Judgment

advertisement