Wordsworth and Modernity - ANU eView

advertisement

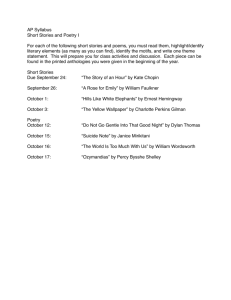

MOTIVATION VIA LOSS: WORDSWORTH AND MODERNITY Andrew Willcocks∗ William Wordsworth’s poetry is often confounded by a sense of chaos, in which the author loses his sense of self to the disorder of the industrial revolution and the social effects of modernity. Several of Wordworth’s works –including The Prelude– reflect this modern chaos and loss of identity through the literary phantasmagoria of early 19th century London. This essay argues that rather than allowing the modern chaos to trump his sense of self, Wordsworth instead calls into play past memories of ordered natural environs, transposing them onto industrial landscapes and the swirling crowds of modernity with a view to affirming a sense of natural order within chaos. William Wordsworth’s greatest poetry arguably uses a sense of loss to attribute a value to the phenomenon of subliminal recollection, as contrasted with the uncertainty and danger of uncharted realms. Rather than settle with the directionless – the lost – Wordsworth prefers to restore natural order to the often chaotic and uncertain landscapes that his greatest poetry describes. In recognising and celebrating the miracle of natural order, Wordsworth retreats into the (frequently glorious) shelter of heterogeneous categorisation, where he can control his thoughts and perceptions – away from the whirling images and melting pot of modern life that, to Wordsworth, hold superficial meaning and threatening disorder. Several of Wordsworth’s poems are motivated by humanity’s chaotic failings and subsequent losses – a motivation that might reveal its source in the changes brought about by the industrial revolution and the French revolution at the time of his writing. These revelations, while worth considering, often produce an incomplete picture of Wordsworth’s ever‐hopeful verse, and are probably more accurately applied to the work of his contemporaries. Much of ∗ Andrew Willcocks is in his fourth year of a Bachelor of Arts/ Bachelor of Laws degree at the Australian National University, and is a current resident of Bruce Hall. 180 Cross‐sections | Volume II 2006 Wordsworth’s poetry is not inspired by a sense of loss, but rather uses loss as a motivation to produce a thoughtful and natural order in response to imminent chaos. In order to demonstrate Wordsworth’s valuing of subliminal recollection, one might look at two key works: I wandered lonely as a cloud and Lines composed a few miles above Tintern Abbey. Both poems describe the inherent value of the ability to retreat to real and ordered images, regardless of their chaotic comprehension at the time of experience. I wandered lonely as a cloud famously describes a sea of swaying daffodils in four simple yet highly emotive stanzas. It is in the last stanza of the poem that Wordsworth attributes a valuing of having that ordered memory: ‘They flash upon that inward eye / which is the bliss of solitude / And then my heart with pleasure fills’.1 It is interesting to note that the crowds of daffodils – as ordered in nature – convey no threat or disorder to Wordsworth, unlike the milling humanity of London in Book VII of The Prelude.2 The valuing of recollection in the face of the lugubrious is found in more detailed terms in Tintern Abbey, in which Wordsworth describes the glory and beauty of the area around the river Wye, and the pleasure with which – when difficult circumstances arose – he recalled his memory of the form and frame of the landscape. Most important in identifying his subliminal recollection are the lines: ‘And I have felt / a presence that disturbs me with the joy / of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime / of something far more deeply interfused / whose dwelling is the light of setting suns…and in the mind of man’.3 Using Wordsworth’s valuation of the recollection of subliminal order, one might begin to read his poetry with that reference, and find that in numerous poems Wordsworth defends himself against a negative prospect – often a philosophical loss of direction or meaning – with the weapons of pleasurable memories past. In many ways, one can see that Wordsworth’s philosophical wanderings may have pre‐empted literary 1 W Wordsworth, ‘I wandered lonely as a cloud’, in M Abrams & S Greenblatt et al. (eds), The Norton Anthology of English Literature, 7th edn, vol. 2, Norton, New York, 2000, p. 285. 2 W Wordsworth, ‘The Prelude,’ in ibid., p. 348. 3 W Wordsworth, ‘Tintern Abbey,’ in ibid., p. 237. Motivation via Loss: Wordsworth and Modernity | Andrew Willcocks 181 works that focused on streams of consciousness, such as Virginia Woolf’s The Mark on the Wall.4 In the poem Resolution and Independence Wordsworth describes a chance meeting with an elderly leech‐gatherer: a human who is described as blending with nature, and who is integral to the landscape on which he stands. The poem ultimately conveys Wordsworth’s resolution that his personal sadness has made him lose sight of the influence of natural order – that which governs the leech‐ gatherer – on his own life. The resolution to recall affirmative meaning in the leech‐gatherer’s existence in times of sadness or loneliness is announced in the last line of the poem: ‘I’ll think of the Leech‐gatherer on the lonely moor!’.5 In most of his poems, Wordsworth describes an adverse situation of the mind or society, and then provides the reader with his affirmative cure through recollection of natural order. Wordsworth’s constant fear of chaos and disorder is probably reflective of the growing effects of the industrial revolution and the events of the French revolution, which he witnessed first hand. In early October of 1793 he visited Paris, where he witnessed the execution of Gorsas, the first Girondist to be guillotined. Particular to Wordsworth’s fears were mobs of angry and passionate people – again, a feature of the French landscape during the early 1790’s. The fear of the unleashed animosity of humanity is apparent throughout Wordsworth’s The Prelude, particularly in Book VII, where the disarray of Bartholomew Square is portrayed in numerous, quick and distinct lines.6 Although this chapter on the outrageous and intense fair is described at length, it is appropriate here to focus on several summary lines (VII.686‐7): ‘What a shock for eyes and ears! what anarchy and din / Barbarian and infernal– a phantasma’.7 Here Wordsworth describes the crowd’s loss of order as appalling and confusing, indicating that they appear to him like the disordered thoughts of a damaged mind. The words ‘barbarian’ and ‘infernal’ describe the spectacle as base and animal, and Wordsworth compares the crowd to (VII. 725‐6) a ‘perpetual whirl / Of trivial S Dick, The complete shorter fiction of Virginia Woolf, Hogarth Press, London, 1985, p. 83. W Wordsworth, ‘Resolution and Independence,’ in Abrams & Greenblatt et al. (eds), p. 284. 6 W Wordsworth, ‘The Prelude,’ in ibid., p. 350. 7 ibid. 4 5 182 Cross‐sections | Volume II 2006 objects’.8 The loss of definable human order in London makes Wordsworth fear the type of passionate rebellion that the French revolution entailed, hence his questioning (VII.671‐3): ‘What say you then…when half the city shall break out / Full of one passion, vengeance, rage or fear?’.9 Wordsworth’s fears of the riotous mob are lightly contrasted with the opening of Book VII, in which he focuses his poetic attention on a beggar wearing a sign that describes the beggar’s plight. Just as he did with the leech‐gatherer in Resolution and Independence, Wordsworth stops the temporal progression of the moment, and addresses the natural order of the particular situation. The vision of the beggar makes an impression on the narrator, and it becomes apparent to the reader that, in the midst of the chaos, order is not lost – the reader finds the erratic images suddenly subdued, as Wordsworth describes the city standing still at night (VII.660‐2): ‘The blended calmness of the heavens and earth / moonlight, and stars, and empty streets, and sounds / Unfrequent as in deserts’.10 The natural order of the quiet night time city has an immediate effect on the pace of the poem. It is evident that the beggar has inspired a reality of nature that holds true even in a surreal London, only if for a fleeting instant. Several lines later the reader is again quickly swept along with the descriptive body of Bartholomew Square. The crowds of London not only provide a riotous threat to Wordsworth in The Prelude, they also provide a threat to his subjectivity and self‐ definition. In Book VII, Wordsworth describes how, when walking through London, he is almost consumed by it – for a moment nearly accepting anonymity and loss of self (VII.632‐3): ‘Until the shapes before my eyes became / a second sight procession’.11 This loss of definition against the background of the incomprehensible crowd is largely addressed by Wordsworth’s recollection of the beggar, but even this would not seem enough to combat the din and constancy of the images ibid., p. 351. ibid., p. 350. 10 ibid., p. 349. 11 ibid. 8 9 Motivation via Loss: Wordsworth and Modernity | Andrew Willcocks 183 of the crowds. After considering the beggar, and the animosity of the spectacle of Bartholomew Square, Wordsworth delivers his ultimatum that recovers his ordered self in the concluding lines of Book VII (767‐ 72): ‘The Spirit of Nature was upon me there; / the Soul of Beauty and enduring life…diffused,/ through meagre lines and 12 colours…composure, and ennobling harmony’. Essentially, Wordsworth uses the order of nature – and his recollections (‘inspirations’) of it – to create an overriding order of the drama and chaos that threaten to rob him of his self definition and subjectivity in the crowd, whose sheer size and depth he cannot comprehend. In conclusion, it is arguable that Wordsworth’s poetry is affirmative in nature, and instead of settling for a sense of loss, it looks to situations in which loss and despair give way to delight in the order and harmony of the natural world. In many of Wordsworth’s poems, and especially Book VII of The Prelude, the human animal is capable – indeed, likely – to interpret disorder as a form of loss. This tendency, however, is subsumed within a broader and more optimistic world view that revels in the human senses, one of which is the ability to recall and recognise the miracle of the natural order of things. In the face of the disordered world of Britain during the industrial revolution and with the recent French revolution threatening, Wordsworth points to natural order – which he often subliminally recollects from past memories– to provide a vantage point from which to repair and make sense of the modern world. 12 ibid., p. 351. 184 Cross‐sections | Volume II 2006 References Abrams, M & S Greenblatt et al. (eds), The Norton Anthology of English Literature, 7th edn, vol. 2, Norton, New York, 2000. Dick, S, The complete shorter fiction of Virginia Woolf, Hogarth Press, London, 1985.