REACHABLE FROM HERE A sermon preached by Galen

advertisement

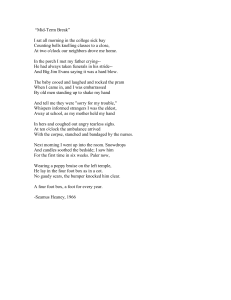

REACHABLE FROM HERE A sermon preached by Galen Guengerich All Souls Unitarian Church, New York City March 1, 2015 The current artist in residence at the 77th Street station of the 6 train is a middleaged white man with an electric guitar and a fondness for Pink Floyd. I’ve seen him perhaps a dozen times over the past number of weeks, usually during the middle of the day as I’m on my way to or from appointments elsewhere in the city. With only a couple of exceptions, the song he’s been playing as I’ve passed through his concrete concert hall has been the Pink Floyd anthem “Comfortably Numb.” Especially during a month that was the coldest February in 80 years and the second coldest in 130 years, “Comfortably Numb” seems the right song to be singing, except for the “comfortably” part. Mostly, we’ve just been numb. It’s been so cold that even the “it’s so cold” jokes have died of hypothermia. The first time I heard the 77th Street troubadour play “Comfortably Numb,” however, was back during the balmy days of mid-December. For weeks, I had been hearing nothing but Christmas carols everywhere I went. I heard “Silent Night” in the bank and “Joy to the World” in the drugstore. Set in this context, I heard “Comfortably Numb” as a protest against the commercialized cacophony of Christmas. No matter the context, the song reminds me that there are experiences to which all of us would like to feel pleasantly indifferent or, as Pink Floyd puts it, comfortably numb. This is especially true with experiences of pain. Sometimes the pain is physical, but more often it is emotional, or social, or professional, or even political. In order to survive and even flourish as individuals, we sometimes numb ourselves to the pain within us and around us. After all, none of us can comprehensively engage, every minute of every day, the full emotional pain of an addiction, or the betrayal of a spouse, or the death of a child, or the sabotage of a friend. None of us can fully engage how we as individuals have failed those who count on us. None of us can fully engage how we as a nation have sanctioned privileges based on gender identity, and race, and sexual preference that add up to institutionalized violence against people who aren’t male, and white, and straight. None of us can fully engage the brutality of Boko Haram, the viciousness of ISIS, the cynical duplicity of the Saudis, or the moral depravity of the weapons dealers and arms traders who profit by keeping the world dangerous. When the pain in our lives and our world becomes pervasive and persistent, who doesn’t want to become numb to it, even comfortably numb? Comfort is a good thing, and if we must numb ourselves in order to be comfortable, so be it. ~1~ © 2015 Galen Guengerich The problem, of course, is that when we are numb to something we are mostly dead to it. The word “numb” derives from an old English term meaning “taken” or seized,” and it applies when all feeling has been taken from someone. To be numb is not to feel anything. We experience this condition as comfortable only because the pain has stopped, not because anything good is happening. Unless we become completely and thoroughly numb, which is to say dead, we eventually want to experience something other than numbness. We want to feel something other than the absence of pain. To do so, however, requires us to grapple with whatever caused the pain in the first place. And whether the cause is our own personal failure or loss, or the moral depravity of others, or political malfeasance in high places, it’s hard to find a way over or around the problem – or even through it. We might as well be marooned on a desert island with the answer in some far distant country. There seems no way to get there from here. On Thursday of this past week, Poetry Ireland Review published a special issue celebrating the life and poetry of Seamus Heaney, the Nobel prize-winning Northern Irish poet who died about a year and a half ago. Heaney was, in the words of Vona Groarke, editor of Poetry Ireland Review, “our best poet, by a country mile.” For this special issue, she approached 50 poets, asking them to choose their favorite Heaney poem and write about what it is they take away from the text. While I am neither Irish nor a poet, I do have a favorite Heaney poem, and I’d like to tell you what I take away from its text. The poem is titled “The Cure at Troy,” and it’s based on a play titled Philoctetes, by the ancient Greek playwright Sophocles. I studied the play many years ago as part of my classics education in college, and it has stayed with me ever since. It’s about the interplay of pain and possibility. In the play, Sophocles tells the story of a soldier named Philoctetes, who was on his way to join the Greeks in their fight against the Trojans when he suffered a terrible accident. He wandered by mistake onto a sacred shrine, and a serpent guarding the shrine bit his foot. Philoctetes’ foot became infected, and he began to cry out in pain. In response, his fellow soldiers abandoned him on a deserted island with nothing but his bow and arrows. For ten years, the Greeks battled the Trojans in Troy, while Philoctetes hobbled around his island in pain, near starvation. Finally, a messenger from the gods told the Greeks that they couldn’t win the war without Philoctetes, who carried the famous bow and arrows of Hercules. Hearing this news, the Greek champion Odysseus went with several companions to bring Philoctetes and his weapons back to Troy. Sick and exhausted, Philoctetes was delighted to see his visitors. Philoctetes asked them to have compassion for him and help him, seeing the trouble life had brought him, troubles from which no human is safe. For his part, Odysseus planned to trick Philoctetes by saying they were going home, and then he would take him to Troy. ~2~ © 2015 Galen Guengerich One of Odysseus’ companions, a young soldier, found himself moved by Philoctetes’ pain. The soldier realized Philoctetes’ troubles could have easily beset him instead, and similar ruin could strike him at any moment. Sobered by this realization, he told Philoctetes the truth. Eventually, the young soldier’s compassion and honesty made Philoctetes willing to go to Troy, where his weapons ultimately enabled the Greeks to defeat the Trojans. Seamus Heaney recounts a version of this tale in his poem “The Cure at Troy.” In one key passage, Heaney writes: Human beings suffer, They torture one another, They get hurt and get hard. No poem or play or song Can fully right a wrong Inflicted and endured… History says, don’t hope On this side of the grave. But then, once in a lifetime The longed-for tidal wave Of justice can rise up, And hope and history rhyme. So hope for a great sea-change On the far side of revenge. Believe that further shore Is reachable from here. Believe in miracle And cures and healing wells. Call miracle self-healing: The utter, self-revealing Double-take of feeling. If there’s fire on the mountain Or lightning and storm And a god speaks from the sky That means someone is hearing The outcry and the birth-cry Of new life at its term. Given the pain that persists through time, Heaney observes, history says we shouldn’t hope for anything different on this side of the grave. The best we can do is to comfort ourselves with poems and songs, even as we are tempted to exact revenge, the self-defeating Trojan horse of justice. But once in a while, Heaney writes, hope and ~3~ © 2015 Galen Guengerich history will rhyme: the great sea-change for which we long will, like a tidal wave, carry us from the land of pain to the land of promise. Our role, Heaney insists, is to believe: “believe that further shore is reachable from here.” I don’t know what pain you feel most persistently today. It may be a destructive habit, or a demoralizing failure, or a debilitating loss. It may be the cynicism of our politics, or the ruthlessness of our economics, or the narcissism of our foreign policy. It may be seeing people each day, whether delivering takeout in your building or languishing in a refugee camp across the seas, whom you know will almost certainly be left behind. You see pain in their faces, and you feel pain in your heart. As you close the door or switch off the television, you’re tempted to let the feeling go numb, so you can be comfortable again. Instead, Heaney says, you have to continue to believe. Believe that further shore where hope and history rhyme is reachable from here. It’s reachable from here. Pink Floyd’s song “Comfortably Numb” appears on an album titled The Wall, which is the third best-selling album of all time in the US. It tells the story of a fictional protagonist named Pink, who endures repeated losses and increasing isolation. Pink suffers from a domineering mother, an absent father, a dysfunctional educational system (hence the song “We Don’t Need No Education”), a manipulative government, and destructive personal and professional relationships, among other insults. Each becomes another brick in the wall of his isolation. Pink also becomes an addict, hence the song “Comfortably Numb.” In the end, however, Pink tries to fight back against the wall his pain continues to erect. “Stop!” he says. As a result of this defiant act, Pink is put on trial. The prosecutor says to the judge, “The prisoner who now stands before you was caught red-handed showing feelings — showing feelings of an almost human nature. This will not do.” After hearing the evidence, the judge says, “The evidence before the court is incontrovertible; there is no need for the jury to retire. In all my years of judging I have never heard before of someone more deserving of the full penalty of law.” The judge then turns to Pink and says, “Since, my friend you have revealed your deepest fear, I sentence you to be exposed before your peers. Tear down the wall!” Pink ends up being saved not by remaining numb to his feelings, but by expressing them — by revealing his deepest fear. His sentence turns out to be his liberation: the wall of emotional isolation and numbness that separates him from the experiences that matter most gets torn down. No matter how far the land of promise lies from the shores of your present pain, Seamus Heaney says, “believe that further shore is reachable from here.” He continues: Believe in miracle And cures and healing wells. Call miracle self-healing: The utter, self-revealing ~4~ © 2015 Galen Guengerich Double-take of feeling. If there’s fire on the mountain Or lightning and storm And a god speaks from the sky That means someone is hearing The outcry and the birth-cry Of new life at its term. The miracle, Heaney insists, is that human beings have the capacity to feel both the depth of life’s pain and the extent of its promise. This double-take of feeling, which reveals both ourselves as we are and our world as it could become, enacts the miracle: the ability to believe that further shore is reachable from here. When that happens, Heaney goes on to say, the result can be astounding – so astounding that it’s easy to think God has shown up to speak or to act. Instead, a different miracle has occurred: “someone is hearing the outcry and the birth-cry of new life at its term.” Whatever further shore you seek, it’s reachable from here. You begin by acknowledging your own pain and the pain of people and the world around you. You begin by tearing down the wall. Shift your focus from what’s painful to what’s possible. Then miracles will start to happen. Hope and history will have a chance to rhyme. You’ll hear the birth-cry of new life — your life. And you’ll set sail for that further shore, now reachable from here. ~5~ © 2015 Galen Guengerich