Institutional Responses to Armed Conflict

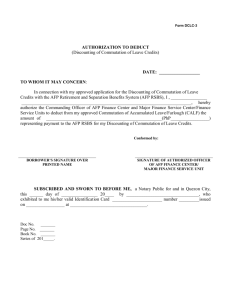

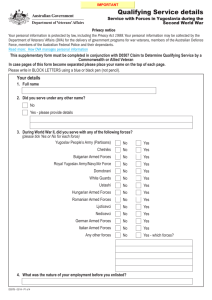

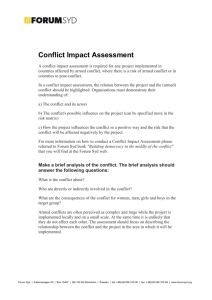

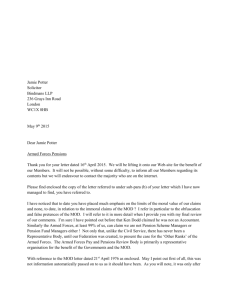

advertisement