Program notes by:

advertisement

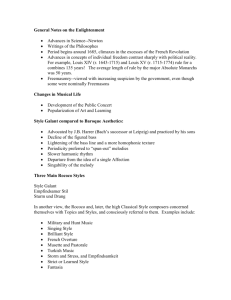

Leslie Tung – May 11, 2012 “Prussian” Sonata No. 4 in C minor, H. 27 Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach 1714-1788 Upon attaining financial independence and jobs of their own, the three of Johann Sebastian’s sons who went into music quickly disassociated themselves from their father’s style. Johann Sebastian’s second son, Carl Philipp Emanuel, is best known today as a composer of delightfully “quirky” music, characterized by expressive pauses, chromatic harmonies and the juxtaposition of oddly unrelated phrases. These qualities, however, were not regarded as quirky in their time; they are associated with two related stylistic categories prevalent in mideighteenth-century Germany: the EmpfinsamerStil (expressive style) and the Sturm und Drang (storm and stress style). Much of Emanuel’s music also belonged to the galant style, which, although somewhat less dramatically expressive, was the more direct forerunner of the sonata form and the music of Mozart and Haydn – among many other composers of the Classical era. For nearly 30 years, starting in 1740, Bach’s patron was the proficient flutist and musically conservative King Frederick the Great of Prussia. Their relationship was difficult at best, and when Bach finally managed to wangle his way out of the king’s employ in 1767, there was apparently little love lost between the two. Bach then went to Hamburg as Kantor and music director, a position vacated by his godfather Georg Phillip Telemann. Bach specialized in keyboard works, including over 200 sonatas. While in the employ of King Frederick, he wrote Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen (Essay on the True Art of Keyboard Playing), the most significant German textbook on the subject in the eighteenth century. He also composed concertos for various instruments and many symphonies. The six “Prussian” Sonatas, printed in 1742 and dedicated to King Frederick, were his first published works. Bearing in mind that he composed the Prussian Sonatas nearly a decade before the death of his father, it is interesting to observe ways in which he struck out on his own. During the latter half of the eighteenth century, compositions in minor keys, comprising all genres, were significantly less common than those in major keys and were always more overtly emotive. The C minor Sonata is no exception. The first movement is rife with those expressive pauses mentioned above, large, expressive leaps and sudden modulations to distant keys. It is in binary form, an ancestor of sonata allegro form, which consists of two large, repeated sections. The first moves away from the tonic, while the second develops the theme and concludes back in the home key. The second movement is an Adagio in the relative major key of E-flat, but no less expressive for being in a major key. It employs some of the same devices as the first movement, but the slower tempo allows Bach to linger more on sighing cadences. The movement also contains a mini-cadenza. The third movement in fast triple time is a remnant of the gigue that concluded the typical Baroque suite. Its two-part contrapuntal texture recalls his father’s so-called two-part inventions. Piano Sonata in C minor, Hob.XVI:20 Franz Joseph Haydn 1732-1809 Franz Joseph Haydn’s long life spanned one of the great upheavals in the economics of the musical profession. It marked the demise of the aristocratic “ownership” of music and musicians, signaling the rise of the middle class as patron, supporter and chief consumer of the arts. No one bridged this transition better than Haydn, who made the shift from darling of the Austro-Hungarian aristocracy to that of London's merchants without offending either. Haydn’s keyboard sonatas span over 40 years of his creative life. The total number is still uncertain since new ones are periodically discovered while others, especially early ones, are found to be misattributed or spurious. At the moment, they number around 60. The early sonatas, composed before the early 1770s, were written for the harpsichord, followed by several intended for either fortepiano or harpsichord. Scholars have definitively determined that Haydn composed the last ones for fortepiano, the direct ancestor of the modern piano. Haydn composed the C minor Sonata in 1771, during the period when he was developing his most expressive voice, in the style of C. P. E. Bach and the EmpfinsamerStil. The Sonata also illustrates the historical shift from harpsichord to fortepiano. The 1771 incomplete autograph of the sonata is clearly headed “Sonata p. il Clavi Cembalo,” (harpsichord) but contains a number of p and f dynamic markings applicable only to the fortepiano or clavichord. When the completed Sonata was published in 1780, together with five others composed in that year, they were marked as “Sei Sonate per il Clavicembalo o Forte Piano;” the many dynamic markings making them clearly more suitable for the fortepiano. The six sonatas were dedicated to Maria Katerina and Franziska Auenbrugger, the talented daughters of a Viennese physician who, according to Haydn, possessed “genuine insight into music equal to that of the greatest masters.” At the time, Haydn characterized the C minor Sonata as “the longest and most difficult” of the set and placed it at the end. The Sonata belies its original designation for harpsichord in more than its dynamic markings; the repeated arpeggio triplets for left-hand in the first movement are more characteristic of pianistic writing. On the other hand, the extensive use of ornamentation – always part and parcel of Haydn’s keyboard style, harks back to the harpsichord tradition. The Sonata also represents a milestone in the formal structure of the solo sonata. In all the movements Haydn uses the extensive development sections to explore all the expressive capabilities of an expanded harmonic palette. Perhaps mindful of the proficiency of the dedicatees, Haydn also includes passages requiring virtuoso technique, including rapid fingering and hand crossing. Piano Sonata in F major, K. 332 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 1756-1791 From around the middle of the eighteenth century, the fortepiano, rapidly displaced the harpsichord as the favorite keyboard instrument. The instrument was, however, still in its infancy, and it would take nearly a century to bring it to the thundering grand piano of Liszt’s time. While there was rapid progress in fortepiano design during Mozart’s lifetime, even his best were still modest instruments of five octaves, limited dynamic range, weak wooden frames, uneven key action and unreliable damping. While some virtuosi, including Mozart himself, performed on the instrument, it was primarily for the home use of amateurs. Mozart’s embrace of the fortepiano gave it a healthy boost in professional circles and spurred manufacturers to constantly add improvements and innovations. Still, the limits of the instrument dampened his interest in the solo piano sonata, which never achieved the significance in the corpus of his works as it did in Beethoven’s–only a generation later. Until Mozart reached the age of 18, his solo sonatas were actually improvisations at the keyboard and were not written down. Only the sonatas for four hands, to be played with his sister Nannerl were, per force, notated. The date of composition of the Sonata in F major, K. 332 is uncertain, but probably dates from Mozart’s trip to Salzburg in 1783. The visit was an attempt to reconcile with his father, who had objected strenuously to his son’s move to Vienna, his subsequent marriage, and the composer’s refusal to name Leopold godfather to his first son. While the Sonata’s first two movements are certainly within the range of amateur abilities, the fiery finale makes considerably greater demands on the pianist. The first movement contains five distinct themes, two of them the formal so-called first and second themes of the sonata allegro form, two others, transition or bridge themes, and a final closing theme. The first bridge theme in the relative key of D minor, involves an abrupt change of texture and mood between the two “principal themes,” which hardly contrast at all with each other. In place of an extensive development section, Mozart introduces an entirely new theme. The effect, therefore, is more like that of sonatas of Domenico Scarlatti (1685-1757), which frequently began the second half with new musical material. The second movement is a simple two-part form, with its simple broken chord, or “Alberti bass,” accompaniment. It reiterates the major/minor contrast set up in the first movement. While Mozart’s autograph manuscript indicates no variation in repeated sections, the published version shows an elaborately ornamented second half. In concert, Mozart had probably improvised the embellishments of the repeats. In his bridge passage in the first movement, Mozart hinted at the Sturm and Drang of the finale, also in sonata form. Here, within a larger context of rapid sixteenth notes come abrupt pauses and sudden shifts of key and texture. As in the first movement, the development section introduces new lyrical thematic material. Despite the opening bravura of the finale, the coda seems to fade off into the distance. Piano Sonata No.14 in C-sharp minor, Op. 27, No. 2 “Moonlight” Ludwig van Beethoven 1770-1827 In the period 1800-1802 Beethoven composed about a dozen piano sonatas that signaled his break with the rigid classical sonata structure, experimenting with the balance, order and character of the various movements. In the Piano Sonata Op. 27, No. 2 he made a significant departure from the traditional sonata structure of the period. Because of its unusual movement sequence, slow-fast-faster, he was reluctant to name it simply sonata, but called it “Sonata quasi una Fantasia” (almost a fantasy). Composed in 1801 and published a year later with a dedication to his pupil and good friend Countess Giulietta Guicciardi, it became an instant favorite with the public. Its mood fitted well into the burgeoning romanticism of the time. But its popularity irked Beethoven, who complained to pianist and composer Carl Czerny: “Everybody is always talking about the Csharp minor Sonata. Surely I have written better things. There is the sonata in F-sharp major (Op.78) – that is something very different!” The popular name “Moonlight” originated in 1832 in a review by the German romantic poet Heinrich Rellstab, in which the first movement was likened to a boat wafting on the gentle waves of moonlit Lake Lucerne in Switzerland, The Sonata opens with an ascending three-note arpeggiated motive that is used ambiguously, as a true theme and as a gentle ostinato accompaniment throughout the entire movement under the languid main theme. This motive is deceptive in its simplicity, and, like the slow movement of the later Seventh Symphony, shows what a master can do with a series of repeated notes. The Allegretto is a light scherzo and trio, serving as a short interlude before the intense Presto finale with its assertive rising arpeggios and sudden mood changes. While the passionate mood of the final movement contrasts with the opening of the Sonata, both movements are based on arpeggios and employ secondary themes based on repeated notes. Program notes by: Joseph & Elizabeth Kahn Wordpros@mindspring.com www.wordprosmusic.com