D1.1_Part1_Corruption and the Opposite to Corruption

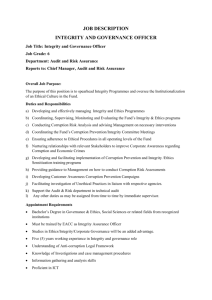

advertisement